When I think of the Chicago blues, particularly the era of the “electric blues,” I usually think of the legendary performers on the Chess label, most of whom are dead and gone, the label now operating as part of the Universal Music Group. A few small labels, like Alligator Records, which started in 1971, Earwig Music (founded in Chicago in 1978 by Michael Franks) and Red Lightnin,’ established in the UK in 1968, have catalogs of older blues recordings or distribute “contemporary blues.”

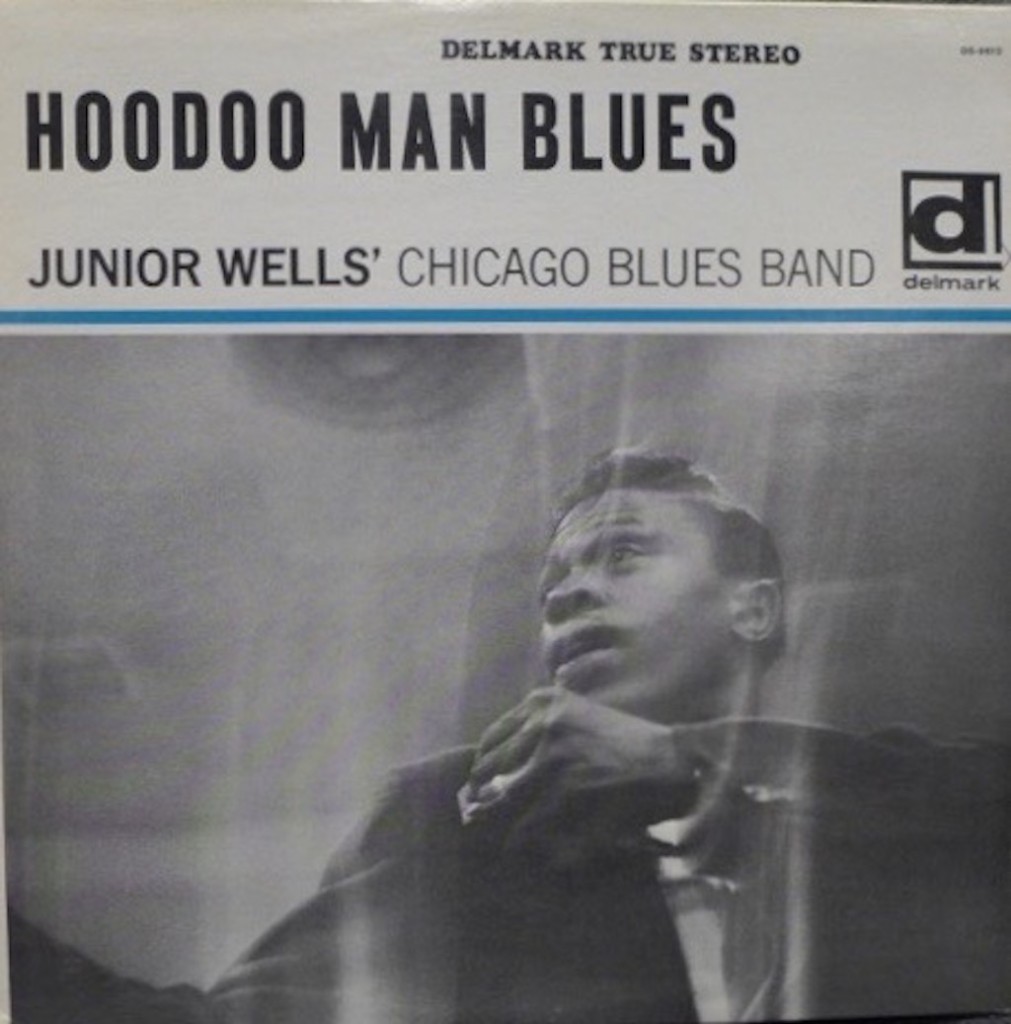

But Delmark Records, founded in St. Louis in 1953, and based in Chicago since 1958, is not only one of the “original” Chicago blues labels, but still remains in operation today. Delmark is also still run by its founder, Bob Koester, who is a legendary figure in his own right (and graciously agreed to supply me with information concerning the record). Koester produced and Delmark released “Hoodoo Man Blues” in 1965. The record has never gone out of print (except for a few months when Delmark moved its offices). And look up any list of “essential” blues records and it is there. There’s good reason for that.

Though he had not yet been discovered by a national audience when the album was recorded in September of 1965, thirty year old Junior Wells was a well-established harmonica player and vocalist on the Chicago blues scene. He made his first recording as a replacement in Muddy Waters’s band for the legendary Little Walter in 1952. By the time of the “Hoodoo Man Blues” sessions though, Wells hadn’t recorded in more than two and a half years, though he’d cut more than a dozen singles for various small Chicago labels starting in 1953, and even made the national r&b charts briefly in 1960 with “Little By Little” on the Profile label. For these sessions he was joined by twenty-eight year old guitarist Buddy Guy. Like Wells, Guy was known in Chicago, and had recorded with some success for the Chess label. Thinking that he was still under contract to Chess, Koester credited Guy as “Friendly Chap” on initial releases of this album. I asked Koester about the “credit” issue and was told: “I called Leonard Chess and he said, ‘OK, use the sonofabitch but you don’t use his name and he doesn’t sing.’” Koester told me, “I later discovered that he didn’t have Buddy under contract, so I used his name, with Buddy’s blessing.”

By the time “Hoodoo Man Blues” was released in late 1965, the public’s attention was elsewhere–Americans were discovering electric Chicago blue[s] but it was being channeled by a wave of British musicians who acted as interpreters of our own musical heritage: the Rolling Stones, the Animals and the Yardbirds. All made popular breakthroughs with the U.S. audience in 1964 and 1965. On the US folk scene, there was some interest in older acoustic rural blues artists, and even in elder statesmen of electric city blues such as Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, but sales for Chicago and other urban blues artists had peaked in the 1950s, when the market was driven by singles purchased in African-American communities.

But “Hoodoo Man Blues” sold when it was released, and continues to sell today. It wasn’t just that it carried on a tradition (it did), but that it captured something very elusive–the emotional essence of what real electric blues, played live, sounds like. For that reason, it is a timeless recording.

Listen to the track “In the Wee Wee Hours”: it evokes the feeling of being in a small, dark club late at night, the sting of cigarette smoke in the air, drinks leaving wet rings on the tables. The cymbal roll opening and delicate filigree of guitar build behind a half-wail, half-whispered voice; whipped by that mouth harp and the steady beat of the drums, bass and hi-hat, this brings you into the music like few tracks I’ve ever heard. You don’t marvel at the playing because it isn’t about the individual instruments or performers; it sucks you in to a time and place that looks and feels far different than your listening environment (unless you are sitting in a late night bar in Chicago 50 years ago). One of the reasons for this, according to Koester, is that he told Junior Wells not to limit himself to 3-minute tracks, because Koester had no plans to release any singles.

The title track has a little more of that “macho” bluesman quality for which Muddy Waters was famous when he invoked the supernatural. “Snatch It Back and Hold It” lets Wells shine as he riffs against a fast-paced piece of R&B funk; “Ships on the Ocean” gives the un-named Buddy Guy a little room to switch from mandolin-style licks to his now characteristic spidering repetition on the frets, with the flare of Junior’s harp playing the “horn” part. There are some covers here, like “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl” and “Hey Lawdy Mama” that don’t cut any new ground, but they sound just right. “You Don’t Love Me Baby” is a blueprint for the later version on which the Allman Brothers rode to fame on their live “At the Fillmore East.” “Chitlin Con Carne” just swings: if you aren’t moving to this one, you might be dead.

There’s a lot here, and you get a sense that it couldn’t be duplicated today, no matter who was playing or recording it.

The band, with Jack Myers on bass and Bill Warren on drums provides a heartbeat to this recording that change rhythms with the mood and never gets in the way. The engineer, Stu Black, who went on to engineer other classic blues recordings for Delmark, Chess and Alligator, captured Wells and the group vividly in a spare setting with relatively primitive equipment. I asked Koester, who produced the album, about the recording: “The studio, located at 230 North Michigan, was on the second floor of an office building and used tube gear. It was recorded direct to two tracks and the entire album was recorded in seven hours over two sessions. Many were single takes.”

There is some lore about missing or erased tapes from these sessions. Koester said that one fifteen-minute tape was taken by a musician who probably thought it was a blank tape. It contained one tune each by Buddy and Junior, as well as a duet of them both singing. According to Koester, “I hoped to release that on a Buddy Guy LP.”

The record was well received at the time, although “DownBeat” magazine gave it only two stars. (Koester told me that the writer, Peter Welding, didn’t care for James Brown and thought Junior was too much like him). It nonetheless outsold any other Delmark release in its first year.

I recently got the opportunity to listen to a mint condition first pressing of the album, in mono and stereo. They were quiet, impeccable sounding copies, which only made it easier to get immersed in the music. My “go-to” copy is an “audiophile” reissue that was cut by Analogue Productions at 45 rpm. But you can still buy the “standard” vinyl LP from Delmark. Although it is sometimes said to be the first full-length blues album released on LP by Delmark, Koester told me otherwise in our correspondence: “We had recorded and issued ten blues albums before 612 [“Hoodoo”] by Big Joe Williams, Speckled Red, Curtis Jones, Sleepy John Estes, J.D.Short, and Roosevelt Sykes.” It nonetheless introduced Junior Wells to a large, receptive audience and by any other name, it is still one of the greatest sounding Buddy Guy records I own.

Essay by Bill Hart, as published in the National Recording Registry.*

Bill Hart is a well-known NYC-based copyright lawyer whose 34-year career involved a wide range of high profile music business matters. Now retired from the practice of law, Bill teaches an advanced copyright law workshop at UT Law in Austin, Texas, and publishes a web/blog devoted to older vinyl records and music history called TheVinylPress.com

____________________

* The views expressed in this essay are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Library of Congress.