“Sunnyland,” by Elmore James, is a blues track that has been part of my DNA since I first heard it in around 1970. What I didn’t know, until quite recently, is that this song –that I’ve known and loved for 45 years –wasn’t the original “Sunnyland” recorded by Elmore James, but a later cut, recorded in New Orleans in 1961. This version, which is far more distorted and raw sounding than the original, remained unreleased until the end of that decade. It first appeared on a compilation released in 1969 in the UK by Blue Horizon entitled To Know a Man. Shortly thereafter, it also appeared on a compilation released in the U.S. and UK in 1970 called The Story of the Blues.[1] That’s how I first heard it:

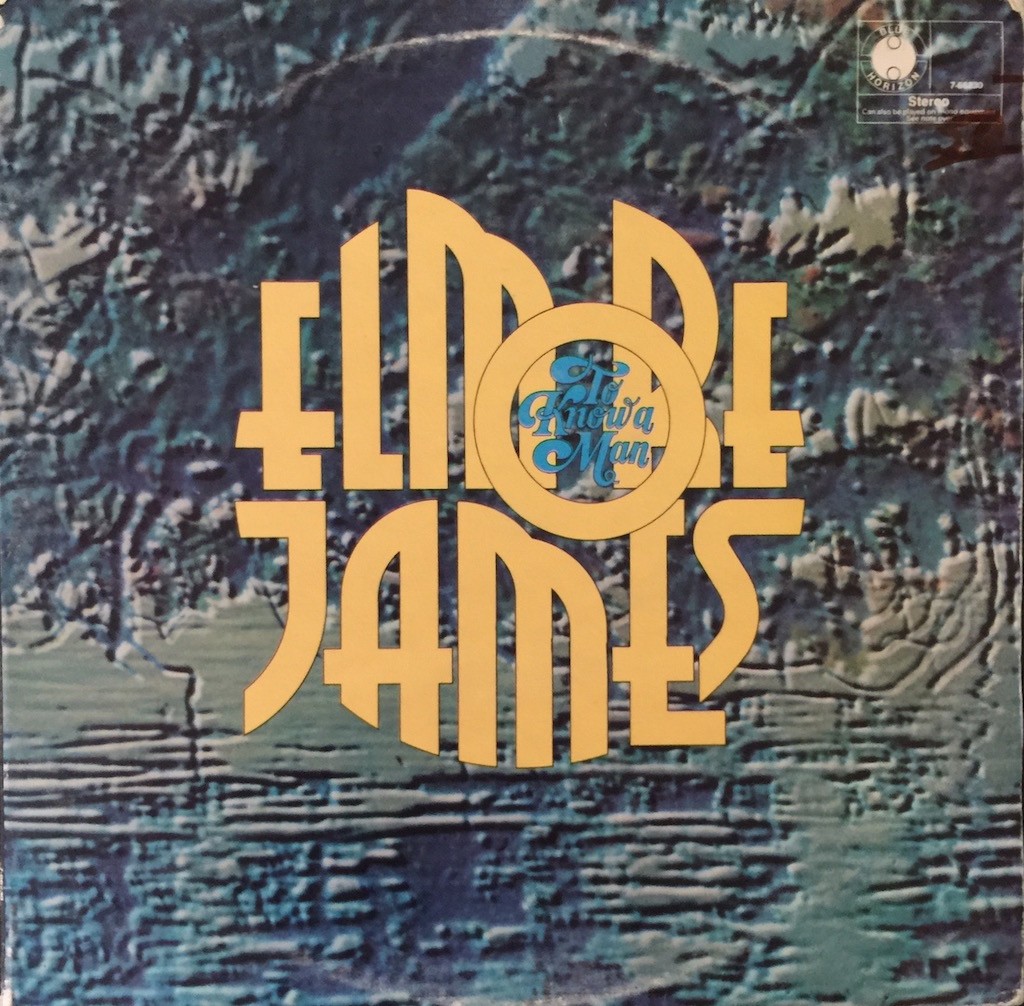

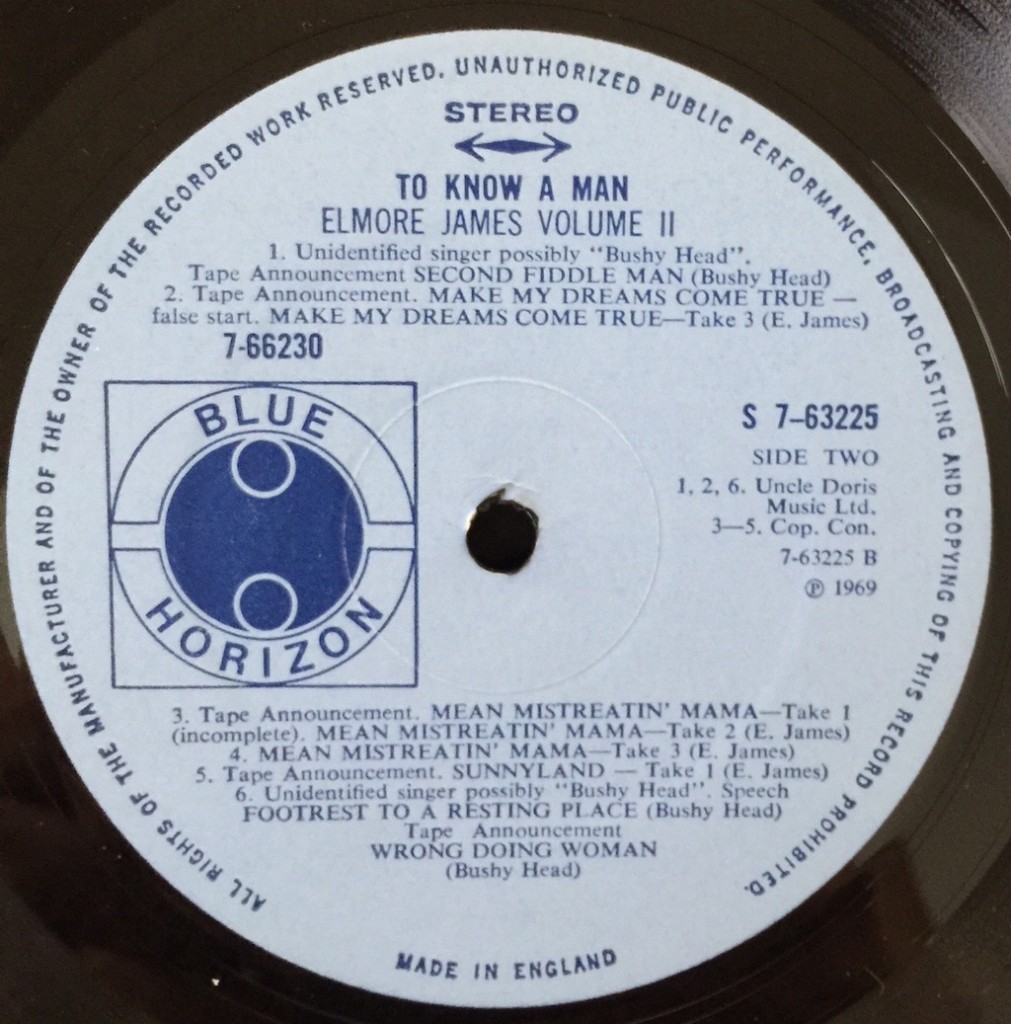

Unlike The Story of the Blues, which covers various artists of different periods, To Know a Man is devoted to Elmore James, and in particular, the tracks and outtakes recorded late in James’ life, from 1961-1963.[2] See generally, an Elmore James discography maintained by Stefan Wirz at Item 53 (on release information for the recording in question). See also, Discogs listing for To Know a Man.

I am not suggesting that you go out and buy The Story of the Blues album(s) unless you are interested in a basic anthology of the blues.[3] I may recommend To Know a Man, once I’ve spent more time listening to it in its entirety:

The original “Sunny Land” as recorded by James in 1954 was more of a loping shuffle,[4] released on Flair Records, and backed by “Standing At The Crossroads.” The songwriting is credited to Joe Bihari (one of James’ publishers under a pseudonym) and Elmore James.[5] But the track that has captivated me all these years was recorded late in James’ life at the New Orleans studio of Cosimo Matassa, a legendary R & B producer and engineer. James was plagued by health problems and embroiled in disputes with the musicians’ union and died not long after these sessions took place.

This 1961 version is far more driving and has a dirty, distorted sound with a blues-shout vocal style that gives the track an urgency the original lacks. It also remained unreleased for a number of years after James’ death in 1963, until it first appeared on the To Know a Man and Story of the Blues compilations as “Sunnyland.”

This later, “hot” track has also been referred to as “Sunnyland Train” but that only adds to the confusion; there is another composition entitled “Sunnyland Train,” credited to Sunnyland Slim (Albert Luandrew)- which is not the same song.

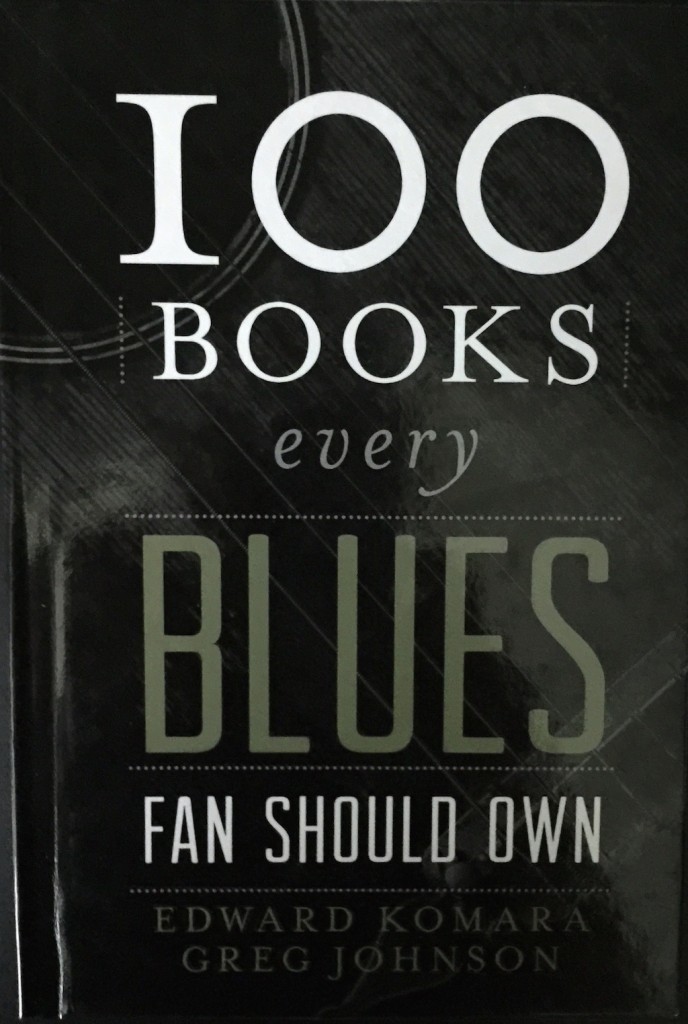

In attempting to sort through this thicket, I received some helpful insights from Edward Komara, who was the blues archivist at the University of Mississippi and is now the Crane Librarian of Music at the State University of New York. Komara is the co-author (with Greg Johnson, currently the blues archivist at the University of Mississippi) of 100 Books Every Blues Fan Should Own (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers). It’s a key to the lock of a gateway –to a vast (and so far, for me, largely untilled) field of scholarship on the blues. I can recommend this book as a resource.

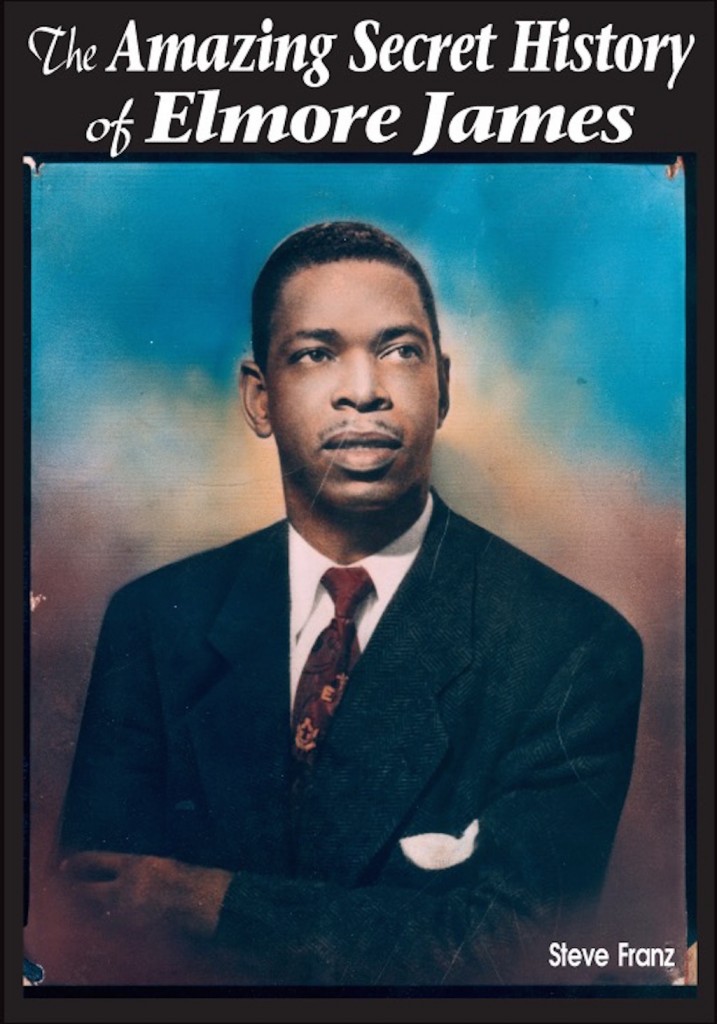

I was also fortunate to correspond with Steve Franz, who has published extensively on the blues and Elmore James in particular, including The Amazing Secret History of Elmore James, (BlueSource 2003).[6] The Amazing Secret History is one of the books covered in Komara’s 100 Books.[7]

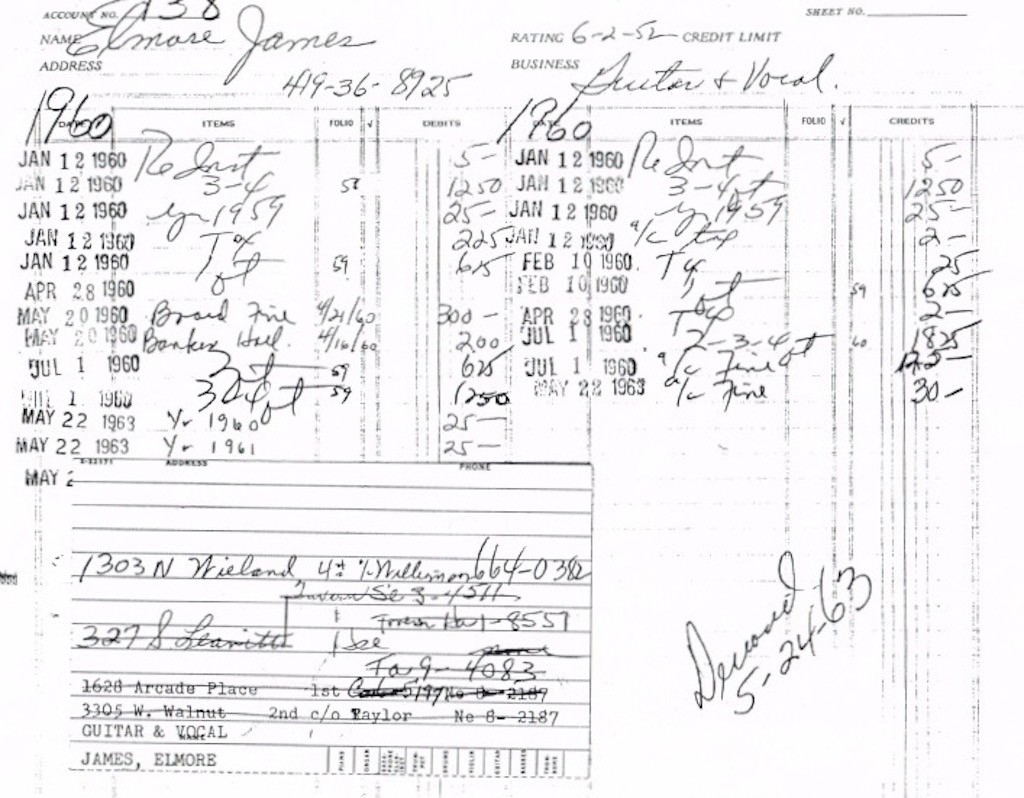

According to Franz, the original 1954 version of the song has a “stop time” beat characteristic of “Mad Love” (referred to by Komara, see note 4); Franz also mentioned “Hoochie-Coochie Man” as another, better known example of the style. Franz believes the 1954 cut was likely recorded in Los Angeles in August or September that year, based on indirect evidence Franz gleaned from session logs at the local musician’s union offices in Los Angeles:

“I never did find a record of the session. The best I could figure was that the Bihari brothers snuck Elmore in at the tail end of a B.B. King session, which was documented and used the same line-up that appears on “Sunny Land.””

Franz also gave me more background on James’ troubles with the musicians’ union in Chicago, which resulted in James being effectively blacklisted from recording sessions.

Even recording in New Orleans could have posed problems for James, said Franz, and the sessions done in Cosimo Matassa’s studio were likely done off hours on a Saturday in August, 1961, based on a third hand source that was rooming with James at the time.

Finally, Franz gave me his thoughts on the difference between the 1954 and 1961 versions of “Sunnyland”:

“The original may have been inspired by John Lee Willamson (a/k/a “Sonny Boy #1), but the later version is clearly influenced by James’ time in Chicago- a transition from rural to urban styles, from soft to loud, from relaxed to urgent. The 1961 “Sunnyland” is a fair representation of James’ style.”

The liner notes of the Blue Horizon release are also instructive in this respect:

Although James is often referred to as the “King of the Slide Guitar,” and blazed the trail for later hard rock-blues guitarists like Hendrix, the Allman Brothers and Stevie Ray Vaughan, Elmore James wasn’t just an inspiration — James was already there, cranking out distorted slide licks with a hard-edged vengeance.[8] This version of “Sunnyland” is, to me, essential Elmore James and has been included in numerous compilations since its first, belated release.

♣

I want to thank both Edward Komara and Steve Franz for helping me to unravel some of the threads to this song. I’m a reluctant, and admittedly amateur, blues scholar: I dove into this solely to identify a particular recording. In the process, my respect for the real scholars of early blues has grown immensely.

_________________________

[1] Paul Oliver, an architectural historian and author of a number of writings on the blues, published a well-regarded book on blues history in 1969. The accompanying album was released by CBS in 1970.

[2] Some readers may know Blue Horizon as the label on which the early Peter Green Fleetwood Mac albums were released. Mike Vernon, a British record executive and producer whose work with a long list of legendary recording artists is deserving of a separate article, founded that label.

[3] And if you were to buy a copy, you’ll need to find an older issue. When The Story of the Blues was reissued in 2003, the Elmore James track, and a few others, were deleted from that compilation, at least on CD. I’m not sure about newer vinyl reissues.

[4] According to Edward Komara (whose work is discussed below), this slower version has a riff reminiscent of, and possibly inspired by, a Muddy Waters track, “Mad Love (I Want You to Love Me)” released by Chess in 1953.

[5] James had recorded for the Bihari brothers beginning in the early ‘50s, though the relationship was complicated by another commitment James had with Trumpet Records. James also recorded for Chess.

[6] Franz also produces a syndicated radio show, “Blues Unlimited” that is broadcast in the States and elsewhere.

[7] Both the Komara and Franz books are available on Amazon. I bought both.

[8] James worked at times as a radio repairman. Some of my reading suggests that he tweaked his gear to get that hard-driven, overloaded sound which ignites the track in question.