I’m listening to Les Paul in 1948. His tone is big, rich, and woody- with added percussive accents when he slaps the body of the guitar. What I’m hearing is vivid, real and alive- in a room thousands of miles and more than half a century away from the garage where these recordings were made.

We sit in a studio that looks like a cross between an old time record mastering suite and something from the bridge of the Starship Enterprise. There is nobody else in the room but the preservation engineer. Nearby stands a library cart full of old discs, each one holding a single track, or combination of tracks from an ‘experiment’ Les Paul conducted in his garage.

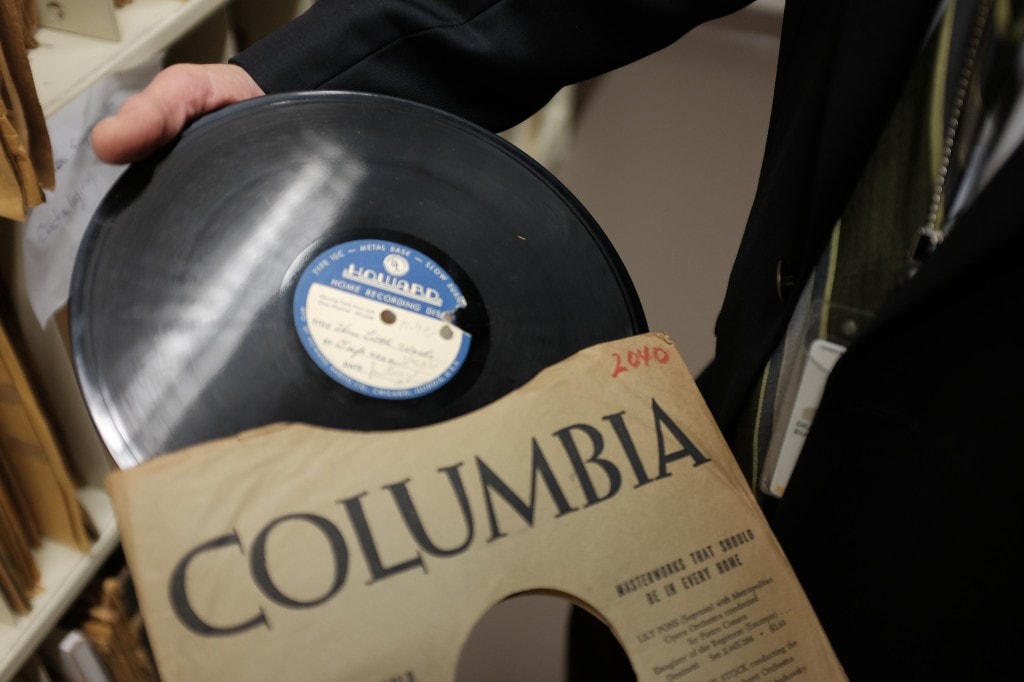

This was multi-track recording, cut to disc (not tape), fully three years before “How High the Moon” made Les Paul and Mary Ford famous, popular artists. Paul would play, cut the track on a lacquer (using a homemade lathe) and play it back on a phonograph while recording another part over it onto another disc, capturing the sounds of the first disc along with his ‘overdub.’ He did this hundreds of times, to eventually release two songs,” Lover” and “Brazil.” The building blocks of this time consuming, creative effort were these discs, which remained in Paul’s possession until his death in 2009. They are fascinating to listen to, and compared to the commercially released record, sound far more immediate and visceral, no doubt owing to the ‘generation loss’ caused by the primitive ‘dubbing’ process. These early efforts by Paul at ‘multi-tracking’ were the beginning of a practice that still dominates most commercial (and amateur) audio recording today- the ability to combine different recordings, taken at different times, to enliven, fix or in some cases, even make possible, certain recorded performances.

The Les Paul discs are a small part of the Les Paul collection that has been donated to the U.S. Library of Congress, whose holdings are vast. I am not sitting in downtown Washington, D.C., though, but instead in a stark modern building nestled in the hills of Virginia some 75 miles southwest of the capitol. Here is where the business of preserving our nation’s audiovisual legacy is a hands-on, day to day activity, not just a noble sentiment.

The Packard Campus for Audiovisual Conservation was opened in 2007 on the grounds of a federal facility that was essentially a Cold War bunker for our money supply. It has been magnificently repurposed by an endowment from its namesake, the Packard Humanities Institute, along with federal funding, to provide a state of the art facility for curating and preserving audiovisual materials- recordings and films.

There are miles of shelving down here, in secure vaults left and right along the corridors of seemingly endless tunnels. The vaults, packed with floor to ceiling rolling shelving units, contain pristine copies of the commercial releases from the (then) big record labels (alphabetized by label, and organized by label catalog number), transcriptions of radio broadcasts, unheard since their original airing and oral histories, spoken in their own voices, of civil war veterans and baseball players from the dawn of the 20th century. It is impossible to get a sense of the quantity, let alone the quality, of what is here.

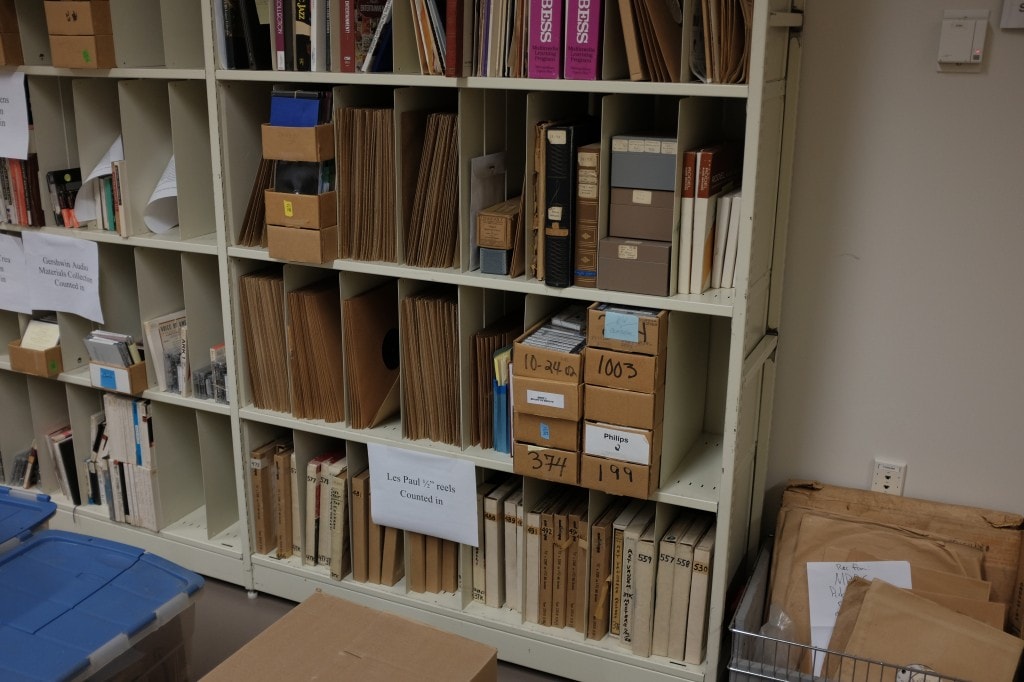

The ‘intake room’ alone is a who’s-who of our nation’s musical and cultural heritage. Wax cylinders stand in rows on shelves next to bulky boxes of 2 inch multi-track tape, and heavy palletized wooden crates sit on the floor in one corner, awaiting cataloging and curating. A wire recording, tangled like fishing line around a spool, holds who knows what; it sits in a bin, with other wire recordings from an old collection that was recently turned over to the Library. Some of the Les Paul materials sit on a shelf next to materials from the Gershwins.

What I am seeing in this one room is just the most recent material to arrive and start the process of being accessioned into the collections of the facility. Rough counts are made of the number of tapes, discs, cylinders or other media; paper and associated ephemera are noted, but at this stage, none of the material is subject to detailed study or inventorying- that will take place later, in the hands of particular specialists assigned to the task. Some of the material is in incredible shape despite its age. Gene DeAnna, the Head of the Recorded Sound Section, tells me that were it not for the private collectors who devote their time, money and expertise to tracking down and preserving this material, much of it would have been lost.

What happens next is part musicology, part archeology, with a little bit of A/V geek and audiophile mixed in- the facility maintains a reference library and has access to a considerable amount of institutional knowledge built up over the years about particular recordings and collections. Some of the materials need to be cleaned or restored before they can even be played. Plasticizers leech, dirt and contaminants fill ancient grooves, magnetic tape must sometimes be ‘baked’ to unglue the fragile magnetic surfaces from their backing materials. All ‘metadata’ including annotations on sleeves, on disc labels, and sometimes on the playing surfaces themselves, is memorialized, and where significant, preserved. (Sometimes, things like wax pencil markings on playing surfaces need to be removed to be able to play the disc).

We go into a ‘cleaning room’ where industrial record cleaning machines stand ready on well-lit work surfaces. Most discs are not cleaned until they are ready to be digitally copied or a scholar or other member of the public makes a request to listen to something in the Library’s catalog. The record will then be carefully cleaned, using a Keith Monks or VPI Typhoon vacuum machine (no ultrasonic machines were in evidence on my visit, though I understand that the Library is considering them), and re-sleeved in a clean inner sleeve. (The original sleeves are kept if they have any artifact value or contain any annotations that may be helpful in research). Eventually the recordings are digitized and those digital copies, not the originals, will be what is called up and accessed for later use.

In the room with the Les Paul tracks playing, two different digital copies are made- one is essentially a ‘flat transfer’ of exactly what is on the disc, no equalization of any sort being applied. The other digital version has been equalized, although it is uncertain exactly what curve Les Paul may have used when the discs were cut. I have been listening to the EQ’d versions, and they sound lifelike.

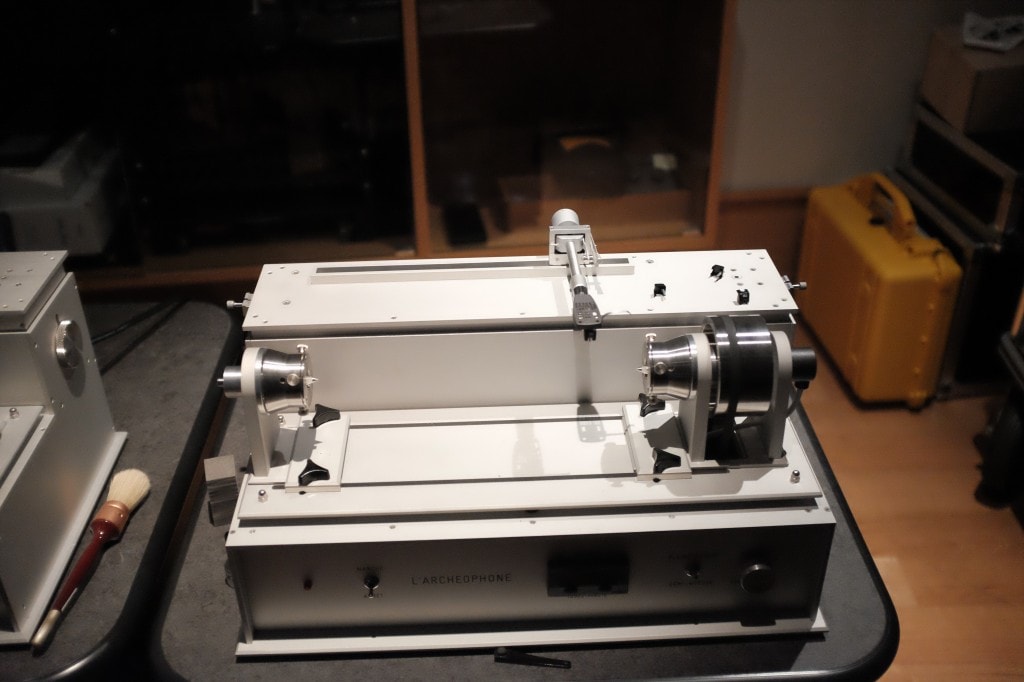

Wax cylinders present a different challenge. The facility has some purpose built modern cylinder players- these use lateral tracking tone arms and cylinder turning machinery that looks like a laboratory grade lathe. Tape machines- mostly Studers- abound, in the various studio suites, even in the hallways, on rolling stands.

The underground tunnels from the old bunker have also been restored and that is where the storage vaults are located. It is cold down here, the lighting in the hallways has a sci-fi aspect to it, and we are ushered into one room after another filled with countless rows of records. The original collection began with a donation, in the 1930’s, from the Victor company, and from Columbia Records. Today, it exists through a combination of private donations, acquisitions by the Library, submissions originally made to the Library in connection with the copyright registration process and contributions made by various record labels to help complete the collection. The sheer bulk of it is staggering: approximately three million sound recordings, including 1/2 million LPs, and as many lacquers and 78s; more than half a million CDs or CDRs, and a quarter million 1/4″ tapes. I didn’t spend much time inspecting the cassette tapes, but there are over 150,000 of those too!

The collection is roughly divided into two distinct realms- material that has been ‘published’ or commercially released, and unpublished material, from private recordings to unreleased master tapes and outtakes.

The commercial releases run the gamut, from labels large and small (Vanguard, home to so many great folk records, is adjacent to Vertigo, the progressive label from the UK that I have recently been exploring), in alphabetized rows of fresh, unmolested jackets. The Columbia and Victor catalogs, which seeded the collection, are now just a fraction of the collection. (I hadn’t known that the “Columbia” catalog took its name for its headquarters location in the nation’s capitol- a choice driven by the need in those early days of commercial recording to be in proximity to the US Patent Office, much like the early days of film, an enterprise fraught with patent battles that drove the industry west to avoid the reach of Edison’s agents).

It isn’t often that I get to see 40 or 50-year-old records in ‘new’ condition. You could plunge into Chicago-style electric blues for months, if not years, just by the riches on the ‘Chess’ or ‘Delmark’ shelves. Plumb deeper, and you’ll find the field recordings (most of the Lomax recordings are lodged in the American Folklife Center of the Library’s “main” campus) or the ‘race records’ on 78 that were, in their day, simply fodder to sell phonograph machines.

The unpublished collections are finding their way to the surface. Through arrangements with rights-holders and donors, some of these recordings are now accessible online, through portals like the Recorded Sound Research Center (http://www.loc.gov/rr/record/) and the American Folklife Center. Published material can also be accessed though the National Jukebox Project. In addition, anyone can contact the Library of Congress in Washington and make arrangements to hear a selection of material in one of their reading rooms. Members of the public rarely get a glimpse of the “back-room,” though, and that’s why I’m here, in Culpeper.

I had originally made the trip, after some complicated scheduling maneuvers and establishment of my bona fides because I was interested in learning about the Library’s restoration and preservation techniques. More about that in a separate section of this piece. See Part II- Cleaning and Archival Standards of Care.

That mission took second place once I began to see, and hear, what was happening here, behind the scenes. Rather than the clinical atmosphere of a library, or archive, one gets the sense that the staff here enjoys the process of discovery and audio ‘archeology’ every bit as much as the most passionate dilettante. No one seems to take what is stored and restored here for granted- it is a fragile thread, not only to our past, but to the deep, elusive undercurrent of the creative process. Genres are, in some ways, unimportant because the creative process that led to these recorded performances didn’t necessarily respect boundary lines any more than a recording artist would.

What becomes apparent, with access to such a wealth of material, is that the boundary lines of “genre” are for the most part irrelevant: different performers created from the same fabric, hearing and exploring different threads drawn from the same material. The unpublished collections offer a path into time and place that are not limited by defined markets and popular commercial sentiments- the material that did not get commercialized is, in very important ways, even more instructive than the finished ‘product’ of the recordings that did achieve success. Les Pauls’ early multi-tracks are thus, to me, far more interesting to listen to than the commercial releases that resulted; less polished, more visceral, with telltales of how the thing was built, layer on layer.

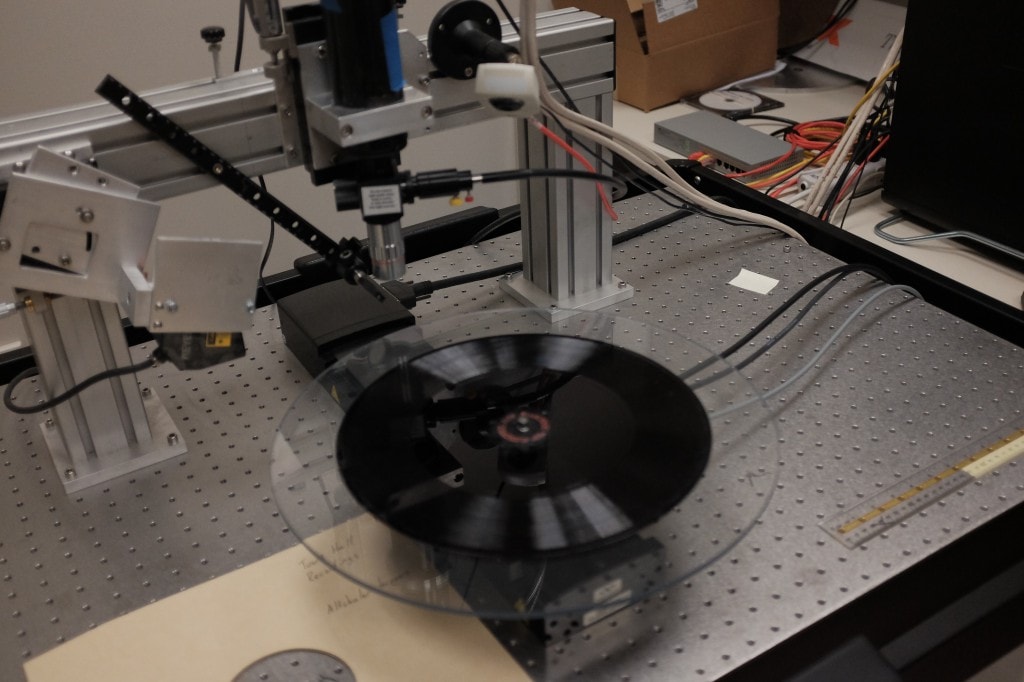

The technology of the time obviously drives not only the format but the content itself. Time limitations inherent in the 78 format give way to longer form recordings made possible by the ‘long-playing’ LP (we often forget why the LP was significant in our digital world). I’m looking at an old Scully lathe in a room chock full of museum quality audio treasures and thinking about the optical scanner I saw in a room down the hall: a device designed and developed by Lawrence Berkeley Labs to enable the ‘reading’ of the grooves with zero physical contact- an innovation, called “IRENE,” that enables mapping and extraction of the content from a fragile medium that may not yield to the stress of physical contact with a stylus.

So too, the brilliant wax cylinder players that take advantage of precision tooling and modern ‘tone arm’ design as a means to extract the contents of an antediluvian medium.

So too, the brilliant wax cylinder players that take advantage of precision tooling and modern ‘tone arm’ design as a means to extract the contents of an antediluvian medium.

That’s another thing that’s brought home here in these Virginia hills- the relationship between music and the technology that enables it. I know that changes in instrument design fostered changes in the role those instruments played, e.g. amplifying the electric guitar took it from a rhythm instrument to a ‘lead’ instrument able to compete in volume with the rest of the big band.

We take for granted that developments in the recording arts fostered changes in how the music itself was constructed and conceived. I’ll admit to a personal bias here, despite my enormous admiration for Les Paul: multi-tracking enabled the artist and the engineer to get away from the sound of a real instrument in a physical space and by affording the ability to layer sound on sound, we get something that is more processed, and ‘less real.’ (That is what I was hearing in the discreet ‘tracks’ of “Brazil” compared to the finished record). No doubt the ability to overdub and create effects gave birth to a form of artistry in the recording process itself, but I’m drawn in more when the reproduction doesn’t sound manufactured, but instead fools me into thinking I’m hearing the actual instrument being played in front of me.

I suppose I also share the modern prejudice that newer recording technologies gave us more bandwidth and a greater facility to capture ‘realism’ of the event- those scratchy sounding 78s playing period music from the 20’s or 30’s always seem to sound tinny and ‘canned.’ But, they don’t have to- equalize them right (at least the electrical recordings made after 1925), get a quiet playing surface if you can, through luck or cleaning or both and despite the limitations in bandwidth, these recordings can be absolutely lifelike. “My” engineer, (Bryan Hoffa, who gave up a stint as a commercial recording engineer to work on audio restoration here at Culpeper), tells me he doesn’t apply noise reduction or de-clicking- he simply equalizes to find the ‘right’ curve at which the record was cut and the vein is tapped. The ‘phono’ preamps at Culpeper are marvels in flexibility, and not only offer the normal variety of obsolete, recognized ‘curves’ but the ability to ‘tweak’ them. This tells me that there is yet another variable few audiophiles account for, since we assume, even in more modern LP playback, that the RIAA curve was strictly observed. I have my doubts, but I’m not sure I want to adjust EQ at home for every post-RIAA LP either.

Obviously, no single visit, or article describing it, could fully capture what is going on at Culpeper. Charting the history of recorded sound, restoring and preserving it, working with modern technology to extract content from primitive media; just figuring out what is on some of the discs, tapes, cylinders and wires is no easy task. What I’m struck by, as we are escorted into the sunlight as our visit concludes, is the degree of artistry involved in this massive effort of curating and restoration- while we may owe a great debt to the original blues artists, like Skip James and Blind Willie Johnson, the collectors and restoration specialists have made it possible for us to hear these performances, many of which would have been lost to the crush of time.

Bill Hart

February 2015

Part II- Cleaning and Archival Standards of Care