Few popular artists have remained as relevant or inventive as Ian Anderson over the course of nearly fifty years. Best known as the flamboyant front man of Jethro Tull, Anderson is a gifted songwriter, showman and performer. He is also someone who has repeatedly redefined himself throughout his professional career.

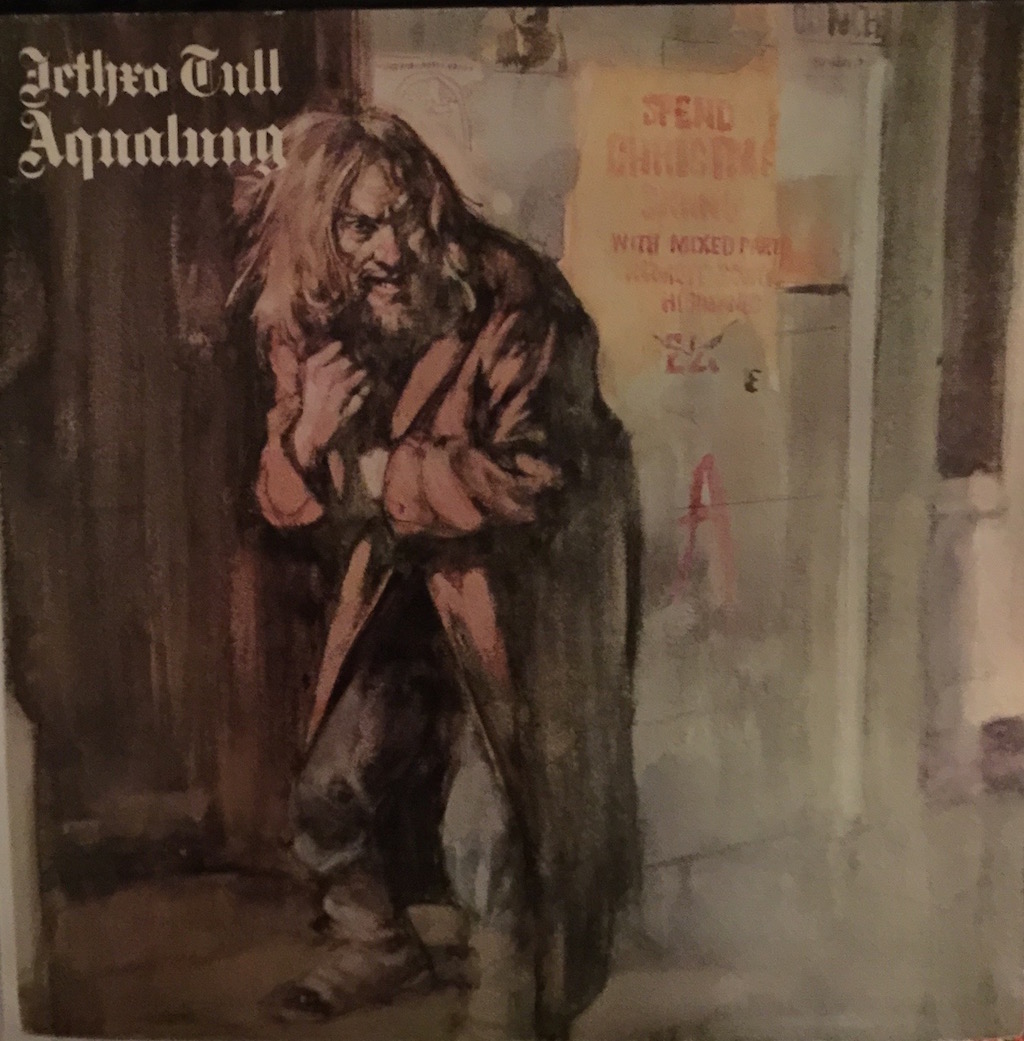

Transitioning from electric blues to minstrel-tinged rock, Anderson established an identifiable sound that became uniquely associated with Tull: drawing on medieval motifs, hard rock, folk and other elements, Anderson and the band invested the troubadour’s ballad with a grandeur and power writ large, contrasting modern, complex and distorted sounds with simple, charming and timeless acoustic passages. The songs are also dark and rich in lyrical nuance and instrumental detail.

These contrasts are where the drama of the music is; Tull seemed to be capable of building tension to a crescendo, shifting to a quiet acoustic interlude or fiery Les Paul guitar line and winding it all down- even in songs of shorter duration. This is not just brilliant performance; it is exceptional songwriting and arranging.

For almost fifty years Anderson led a band that explored rock, folk, world music, metal and medieval ballads, earning the distinction of being originators of the “progressive rock” movement—among such other “first generation prog” luminaries as King Crimson, Pink Floyd and Yes. Yet Tull sounded nothing like any of these or other bands. And Anderson has now reinvented himself once again.

I had the pleasure (and privilege) of interviewing Ian Anderson by phone a few weeks ago. Here is what we talked about:

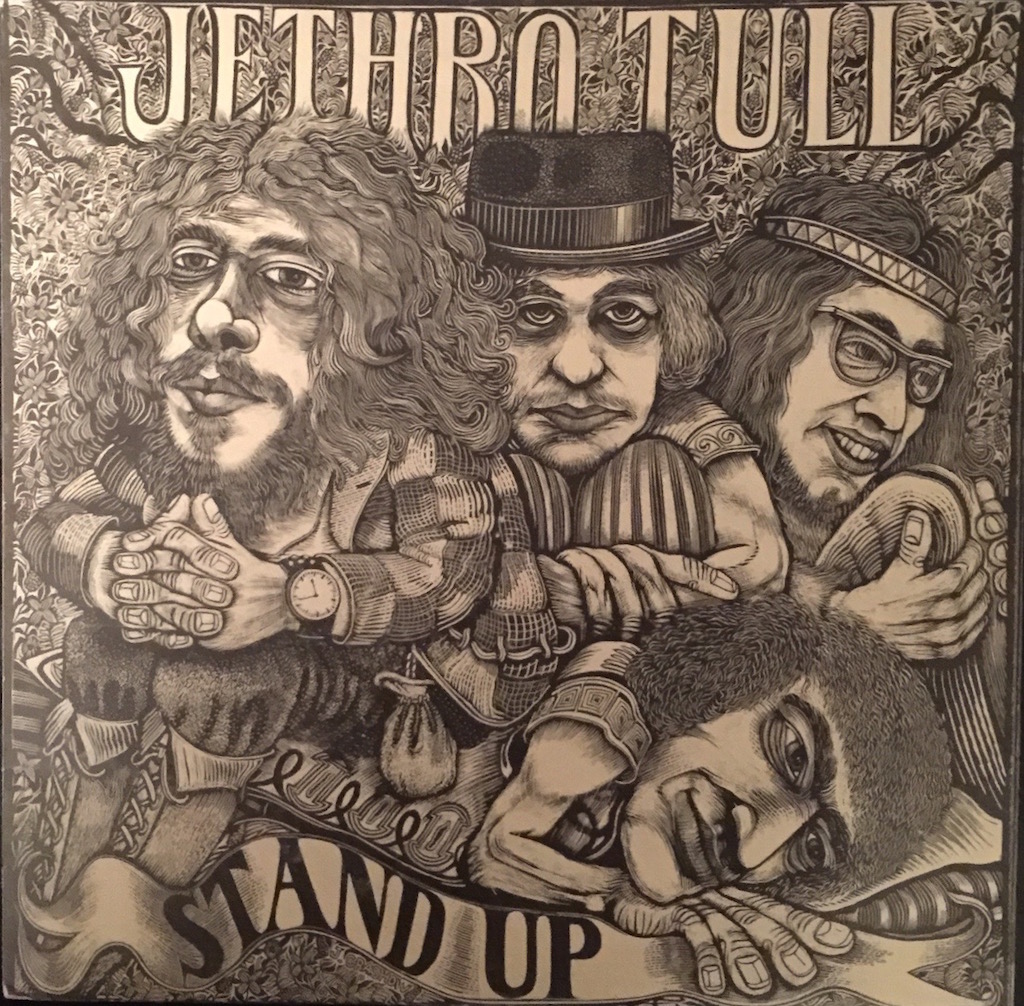

Q: I’m fascinated by that period in which you and Tull transitioned from blues-driven rock to “progressive”—tracing the sound from This Was to Stand-Up, and ultimately to Aqualung and beyond. What were you hearing in your mind’s eye (or ear) that took you beyond the blues?

IA: I was already writing the songs that appeared on Stand Up, the next album, at the time we were working on This Was. I never had the intention to stay rooted in the blues. It was a way to get into the music business. The alternative—writing some radio pop hit— was even less likely or appealing to me. I suppose starting with an electric blues record may have been somewhat cynical or calculated, but it was the vehicle to get me in the door. It enabled me to write and play the music I wanted, which was a mix of things that included classical elements, folk, Asian influences and of course, hard rock. I did not see myself working as a white middle class blues man, and in fact, there were many bands that were doing it better or more authentically.

Q: Terry Ellis was producing Tull at the time. Did he have any role in shaping the sound of the band? Did Chris Blackwell (Island Records founder) have any involvement in the sound of the records?

IA: Neither had a role in the sense of shaping the music. Blackwell, the owner of Island Records, which distributed the Tull records in the UK, was really at a remove from the band. But, I was in constant contact with Terry, who was at first a booking agent and then our manager. Tull was the first act signed to Chrysalis, Terry’s new label. So, there was a lot of give and take with Terry on the business side, but not so much on the music.

Terry was with us on the tours back then and I certainly had discussions with him about the overall aesthetic of what the band was doing. We were all pretty opinionated in those days. But to his credit, Terry knew when to get out of the way.

Q: There was a distinctively British folk movement emerging at the time in England, a la John Renbourn, and Fairport’s Liege & Lief, but what you were doing is much harder, bigger in scale, more dynamic. Did you ever have a name for this sound?

IA: The label “progressive” was used and at first, I thought it fit pretty well. But, later, the term “prog” seemed to apply to a whole range of different kinds of sounds, including music that was quite different from ours. So, it turned out not to be a very precise descriptor in retrospect, but at the time, the term “progressive” did have some meaning applied to Tull.

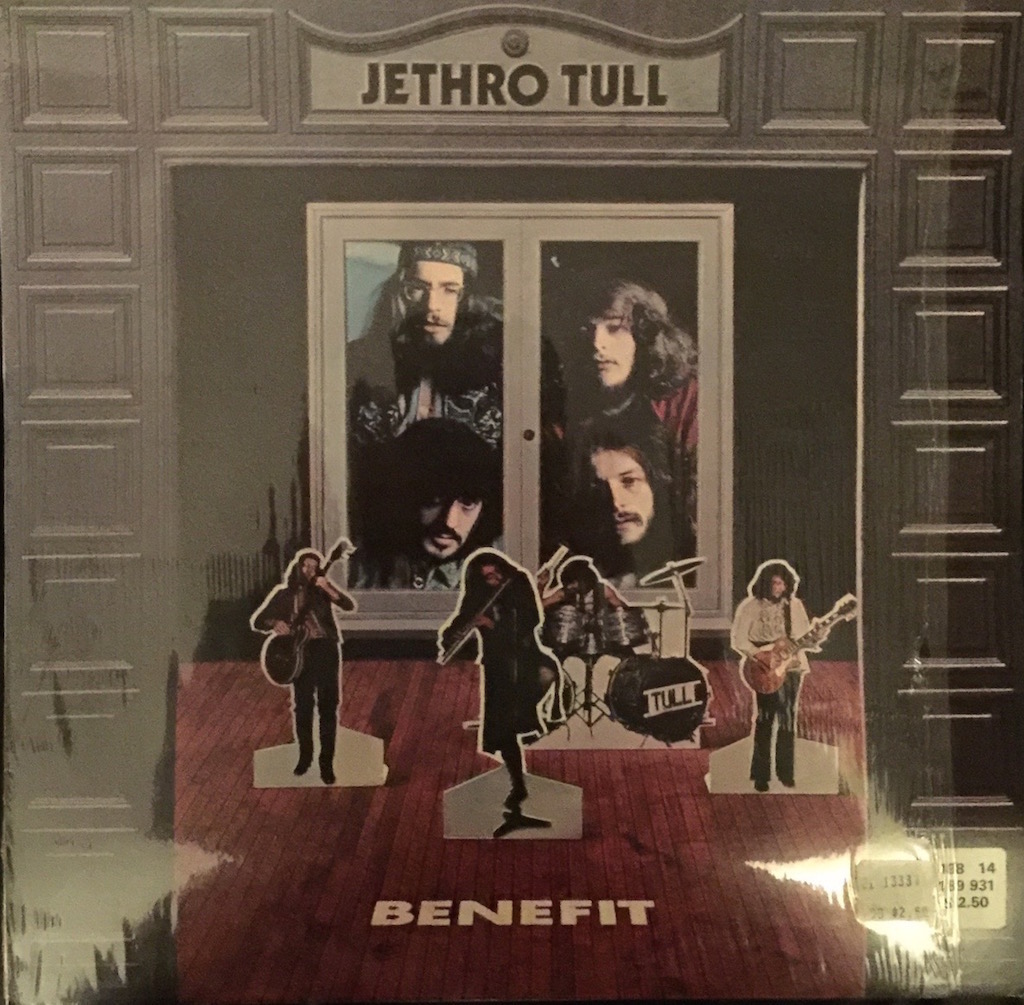

Q: What do you think of Steve Wilson’s remix of Benefit?

IA: I know Steve, who is quite gifted and am comfortable with him. Steve knows how to take advantage of improvements in technology and respects the music. Back in the day, it was all very matter of fact, almost careless sometimes, cigarette ash being dropped everywhere, and no consistent degree of engineering skill was applied. Yes, there were some legendary engineers. But, there were also many limitations imposed by cutting for vinyl then. There is science to this. Steve also understands the music, and has an good sense of what is “right” in the mix in addition to having a very high skill set. The playback limitations of vinyl also are not as big a limitation today. So, we can go back to the multi-track tapes and get a lot more out of them now. I don’t usually have to give Steve a lot of direction in that respect- he knows what we are after- added clarity, tone, the right balance and placement of the instruments. I can listen to his work and know pretty quickly that he is going in the right direction. We are now working on a remix of Stand-Up, which is significant because the album was the template for much that followed.

Q: You’ve cited Roy Harper as an influence. In what ways?

IA: Roy influenced me early on- we played together at several shows- his idiosyncratic way of performing- cheerful passages, mixed with dark material– is still unique in many ways. His 1967 album- Come Out Fighting Ghengis Smith was offbeat and quite influential among a number of artists at the time. Roy was an offbeat character who had no crew, no band, no lorry filled with gear. He would just show up at a gig, guitar in hand. We all envied him as the epitome of the troubadour- a sort of free spirit who did not care about the commercial aspects of the music. Obviously, the reality is a little different than the romanticized image.

Q: You continued to experiment, exploring folk, electronic music, and eventually returned to hard rock, but it is hard to categorize your songwriting in a single niche. Is there some common thread to all of it? How are the themes you are exploring today different than the early Tull era?

IA: I think of myself as an observational writer- I come from a painterly background- a number of musicians from the period had gone to art school, as did I. And my perspective was neither “landscape” nor portraiture. It is more about putting people into a context, and telling a story that way- through a character that is believable in a world I describe through music and lyric. I’ve never been comfortable writing about “me” or my emotions. By basing the music on a character external to me, I can tell a story or convey emotion through the vehicle of a story about other characters.

◊

Anderson’s latest work is an exploration of the person behind the name—Jethro Tull– with which Anderson has been publicly associated since 1968: this reimagining of the historical figure of Tull, an 18th Century agriculturist, takes place in a modern operatic context and draws upon some of Anderson’s best-known songs (with some lyrical adaptations) that fit well into the program’s themes of modern global distress. Anderson wrote some new music for the show, which is performed by him with a live band in conjunction with video projections of the historic characters (played by some pretty serious talent) performing and singing. It all fits together rather seamlessly.

It seems like a lot of parallels exist between the 18th Century of Tull’s world and this one. At the same time, it seems like Anderson is exploring his own past, and in many ways, has come full circle: by reimagining the historical character for which his long-lived band was named, he is finding new meaning in songs he wrote decades ago.

More information about Jethro Tull, the Story, including upcoming tour dates, along with an extensive history of the band and discography can be found at http://jethrotull.com.

⌘

I will be forever grateful to Ian Anderson (and his band, past and present) for the gift of so much powerful, inventive and timeless music over the years. I know I am not alone in thanking him for his extraordinary music.

Bill Hart

February 4, 2016

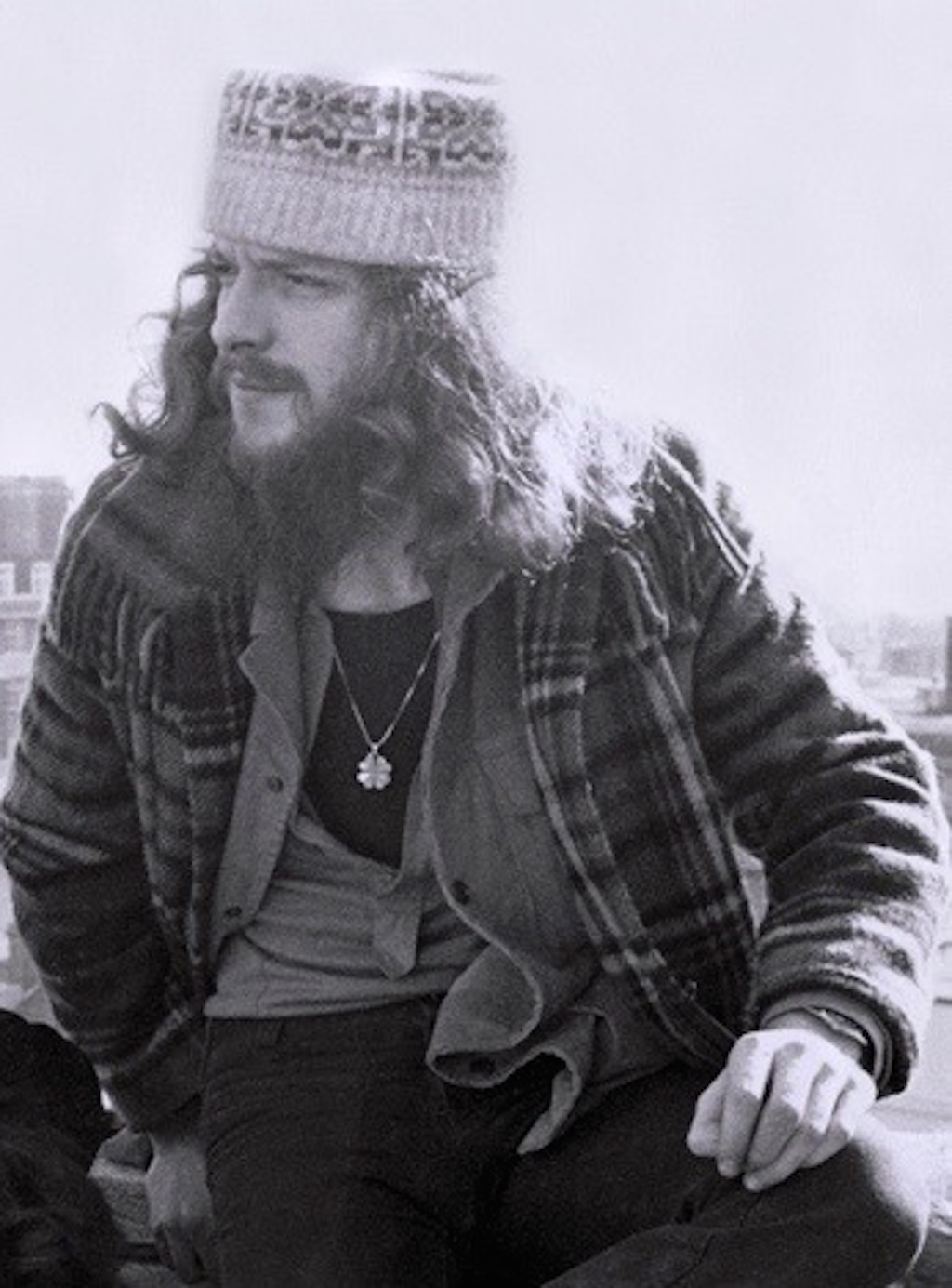

Photo credits:

B&W close-up of Ian Anderson and image of Jethro Tull during the Aqualung era courtesy of Jethro Tull Productions.

Contemporary image of Ian Anderson by Carl Glover.

Image of Jethro Tull, the Story (on stage) by Francesco Pullè.

And a note of thanks to multi-talented Anne Leighton, http://anneleighton.com.