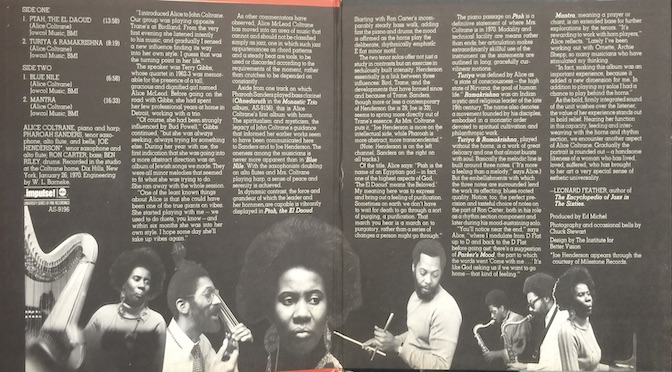

Alice Coltrane, Ptah, the El Daoud and the Coltrane Home Studio (Part I)

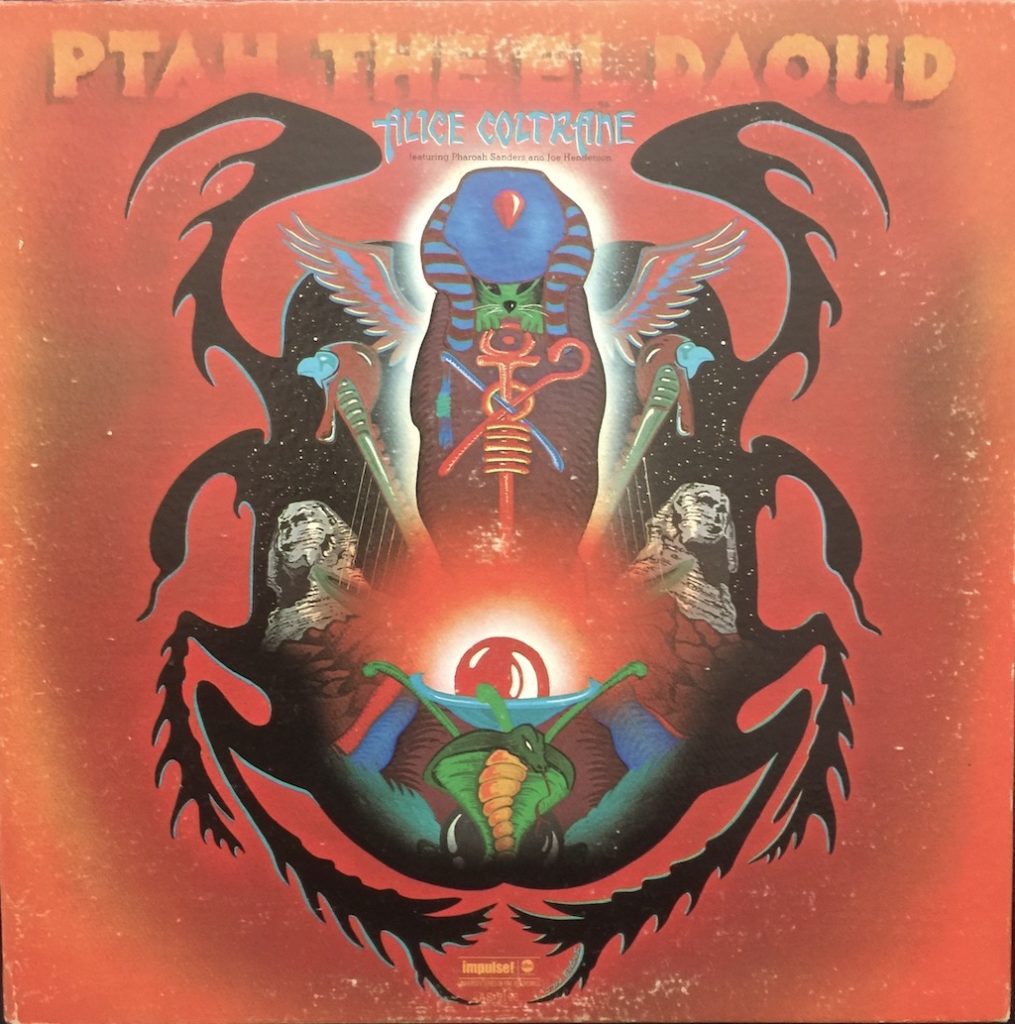

Alice Coltrane’s Ptah, the El Daoud, has an inner luminosity that transcends its performances and composition; it is the rare album that captures not just brief moments of brilliance, but entire passages that transport the listener. The album is all the more remarkable for being out of print on vinyl since 1974. It was recorded in a studio built by the Coltranes in their Dix Hills home that was slated for demolition until a group of preservationists and family members stepped in to rescue it. This is the story of an album and its place of origin that are being brought back to life after almost fifty years.

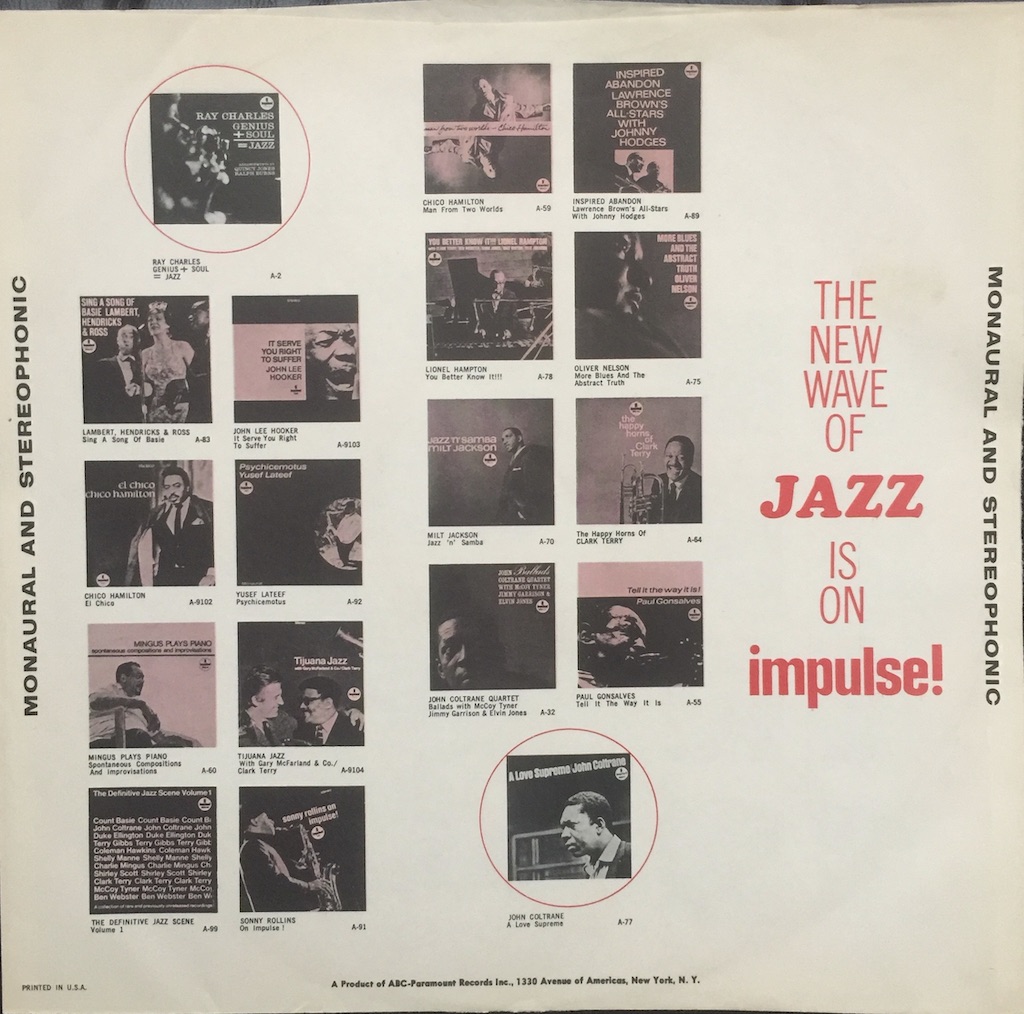

John Coltrane is, of course, revered as a hugely influential player and composer whose short life spanned modern jazz, from Charlie Parker, Miles and Monk to composing and performing A Love Supreme, an album considered the touchstone of “spiritual jazz.” That movement, a search for truth and exploration of the spirit, is a vital part of modern jazz; it has influenced countless players, almost all of whom cite Coltrane as the source.

A Love Supreme was composed by Coltrane at the family’s Dix Hills home in Long Island, where Coltrane had also commenced building a recording studio in the basement. At the time of his death in 1967, the studio remained uncompleted.

John Coltrane’s death cast an even longer shadow over Alice Coltrane (née McLeod), a gifted performer in her own right.[1] With four kids to raise, Alice Coltrane fought against despair to realize her own spiritual awakening, leading to her release of a series of solo albums that stand as monuments in the world of spiritual jazz. At the time, she was clearly overshadowed by the fame of her husband and her music did not enjoy widespread acceptance. Today, these early albums on the Impulse label enjoy recognition for Alice Coltrane’s gifts independent of the renown of John Coltrane.

The Album

Ptah was the Egyptian god of creators whose force of will brought the universe into being merely by thinking it. The album bearing this name was not the first album recorded in the Coltrane studio in their Dix Hills home;[2] Ptah, released in 1970, was followed by Universal Consciousness and by her most famous album, Journey in Satchidananda.

To my ears, the Ptah album fulfills the promise of Alice Coltrane’s talents and the music is ready accessible, making it one of the most satisfying of all of her many albums.

Though she was supported by first tier musicians on these early Impulse releases, there is something that jells on this record like few of the others; there is very little discord, and her ethereal piano technique of fast, arpeggiated sweeps combined with her signature harp playing showcase a mixture of compositional styles that range from traditional blues riffs to lush, more exotic motifs. The horns play a large role here too.

The overall effect is mesmerizing without being monotonous and lively without calling attention to any one moment or performance. It has the adventurous quality of improvisation with none of the awkwardness—everything fits even if it isn’t predictable.

The performances are stellar: Ron Carter on bass, Joe Henderson and Pharoah Sanders on tenor sax and alto flute and Ben Riley on drums.

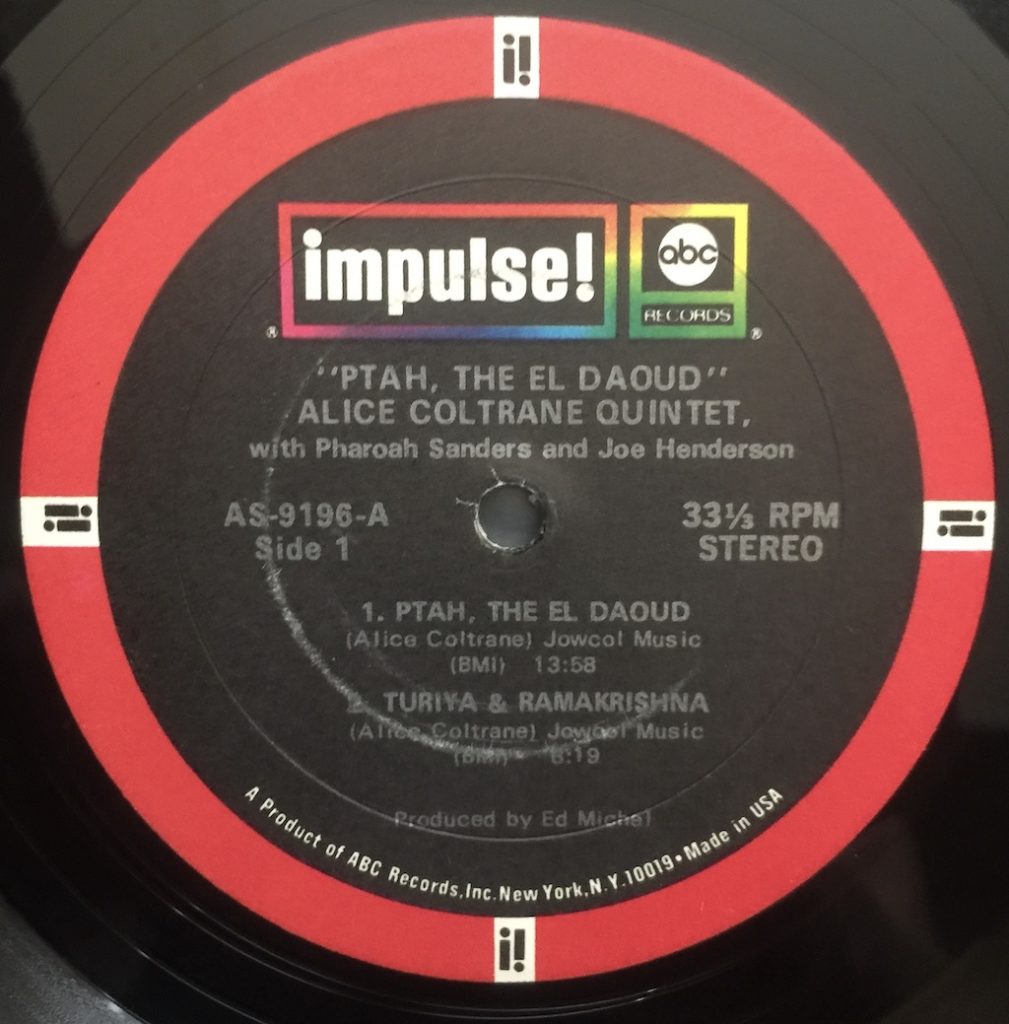

W.L. Barneke, who had worked for Decca (and later MCA) in the States, is credited as engineer. This is one of those records that conveys the ambience of the space where the performances took place and enhances the listener’s immersion into the mood and feeling of the pieces. There are only four tracks on the album:

Side 1

The title track starts off with a bass line that leads into an angular, somewhat Eastern style riff that gives the horns the opportunity to wail, trill and strut, but the bass part is truly magnificent. The piano is abrupt chords as accents until about 7.5 minutes into the track, when the piano takes over, allowing Ms. Coltrane to explore the minor key melodies in an Eastern motif. The drums get a turn—lots of ambience here, setting up a march beat which brings that wonderful bass line in, and we’re back to the start.

“Turiya and Ramakrishna” – in some ways the most traditional track, a blues with a repetitive riff but at around the 2-minute mark, this thing just opens up and it’s glorious. Ms. Coltrane’s playing has structure, it’s finely wrought, but soulful and moody, hitting just the right notes and pulling your emotional strings. What stuns me is how fast she is without ever putting a finger wrong. The band shuffles behind her, setting pace for a slow-paced blues while Coltrane just whirls, changing tempi, key and rhythm. It’s an amazing performance, offset by note perfect bass in counterpoint and the rattle and sizzle of the snare and cymbals. This is probably my favorite track on the record. If one needed a place to start with Alice Coltrane, this would be the song and performance.

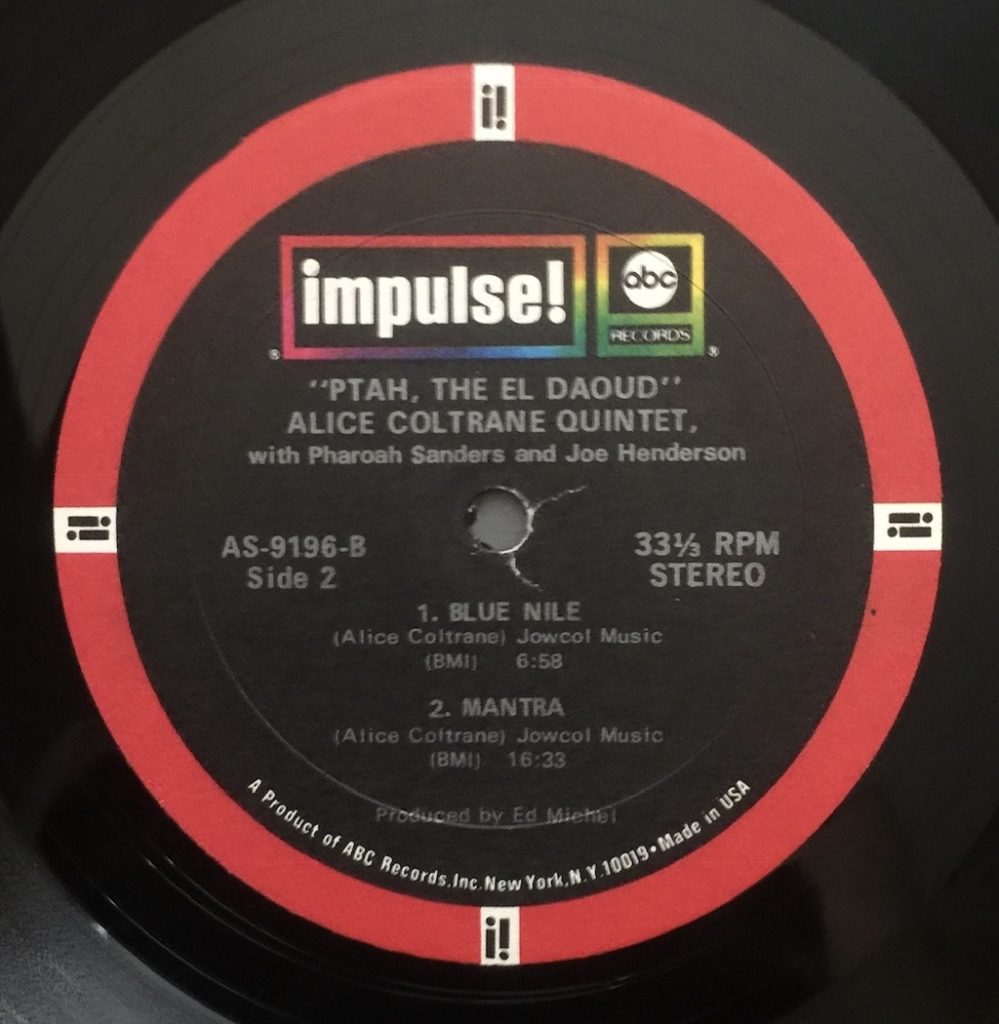

Side 2

“Blue Nile”- If you ever wondered how a harp could fit into a jazz ensemble, here it is: that lush, ethereal string sound is both leading and background, setting the stage for a meditation of flutes that invites a harp solo midway through the piece. Ron Carter is just magnificent here—foundational bass against the harp’s heavenly glistening—and the flutes return in a satisfying finish.

“Mantra”- ominous horns flare, the piano rolls and strikes some dark minor chords that set pace for the horns to ascend. The interplay between Pharoah Sanders and Joe Henderson is fascinating—they weave in and out, working in unison rather than competing. Sanders’ mastery of the instrument is evident here – he’s on the right channel and Henderson is on the left. Sanders’ overblown, multiphonic sound is wild at times, but even at the limit, it’s not cacophony. The piece winds down with some help from the piano, performing intricate studies as the horns come back in harmony with a driving beat to wrap with a flourish.

The album is in some ways a study in contrasts, pushing limits but never straying from an inner path on which Alice Coltrane leads us, marking her own quest for understanding in a life that led her to tranquility out of despair. She was seasoned enough as a featured artist by the time this album was recorded to make it an enduring classic. Why it took so long for the album to be recognized as such probably has less to do with its considerable merits and more to do with the changes in the audience for jazz, now no longer in the mainstream and probably more receptive to the album’s exotic, Eastern influenced sounds.

Pressings

The Impulse pressings from the period generally seem to be inherently noisy in my experience, apart from condition. Finding a clean copy of this record at a reasonable price will not be easy.[3] Unlike the other Alice Coltrane albums from the Impulse era, Ptah was not reissued after the first several pressings in 1970-74.

Given the recent NY Times piece about the Universal fire and the inclusion of Alice Coltrane’s name on the lists of master tapes that might have been destroyed,[4] I suspect that the first generation master tapes for the mixed down version of this album may be gone. I was also informed that these early Alice Coltrane albums, including Ptah, would be reissued this year, leading me to believe that the source would be a digitized copy of some version of the master. Those issues will be taken up in Part II of this piece.

For now, short of paying a premium for a high-grade old copy, the CD from 1996 pressed in Germany is pretty good, perhaps a little short on the natural ambience that the LP conveys so effectively. See https://www.discogs.com/Alice-Coltrane-PtahEl-Daoud/release/759863

But all of this is only part of the story.

The Studio

The studio itself had fallen into disrepair; Ms. Coltrane had relocated to the West Coast in 1972, the house was sold and the equipment stripped from the studio. I was pleased to learn that a serious effort is underway to restore the house and studio. This is being led by members of the family and a group of professionals, including the town historian. The list of Honorary Board members reads like a who’s who of great musicians. We will pick up on the restoration efforts of the house and studio in Part II. In the meantime, the organization’s website offers a fair amount of information:

https://www.thecoltranehome.org

Bill Hart

Austin, TX

June, 2020

__________________________________________________________

[1] See Robson, Universal Consciousness: The Spiritual Awakening of Alice Coltrane https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2016/05/universal-consciousness

[2] Cosmic Music, which combines unreleased tracks of John Coltrane recorded elsewhere, together with recordings made by Alice in the Dix Hills studio, was released in 1968 as was A Monastic Trio, also recorded in Dix Hills.

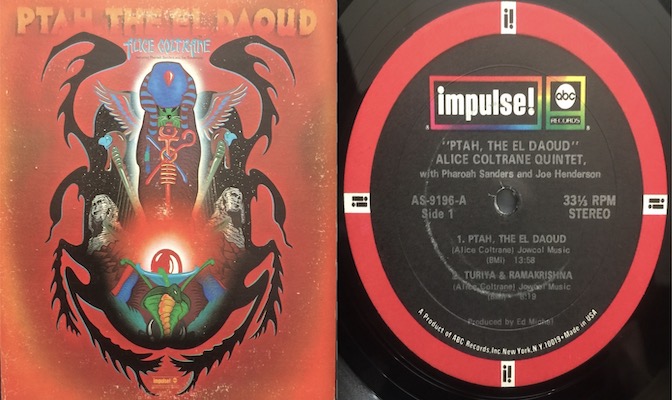

[3] The copy shown here is likely a 1970 pressing, but has the later Impulse logo with a “New York” street address at 6 o’clock on the label. See label images at https://www.discogs.com/Alice-Coltrane-Featuring-Pharoah-Sanders-And-Joe-Henderson-PtahEl-Daoud/release/385862. Compare label from earlier pressing in the same year, https://www.discogs.com/Alice-Coltrane-Featuring-Pharoah-Sanders-And-Joe-Henderson-PtahEl-Daoud/release/8403398

See generally, label variations shown as #4 and 5 here: http://www.cvinyl.com/labelguides/impulse.php

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/11/magazine/universal-fire-master-recordings.html and https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/25/magazine/universal-music-fire-bands-list-umg.html

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.