Comus: First Utterance

The folk music revival of the ‘60s not only revitalized interest in traditional music but also sparked the creation of more contemporary sounds that were influenced by the cultural tides and musical shifts of a turbulent decade. Although it was not released until 1971, First Utterance stands today as a “Ur” album of the psychedelic folk movement; it is a wild ride even by “modern” standards, inured to a post-punk, industrial, hip-hop, noise rock sensibility. It must have been shattering to listen to at the time of its release.

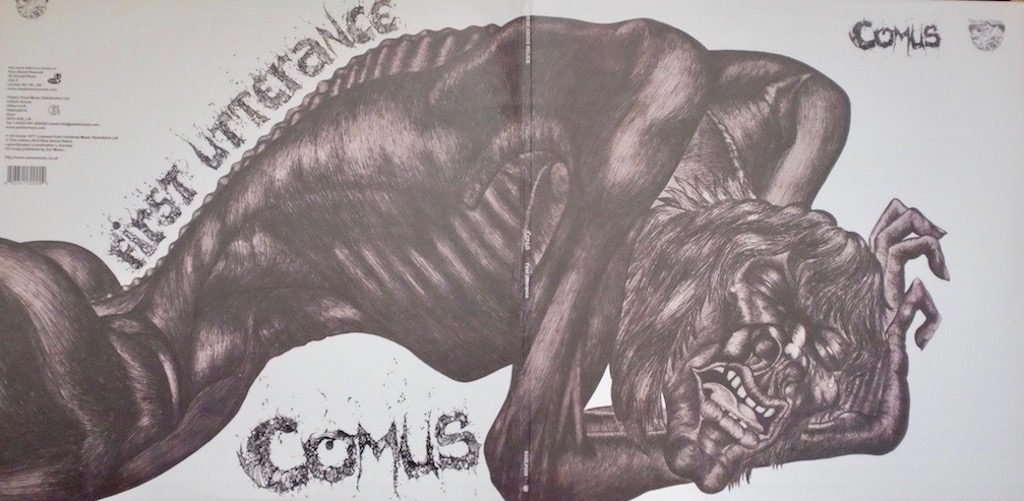

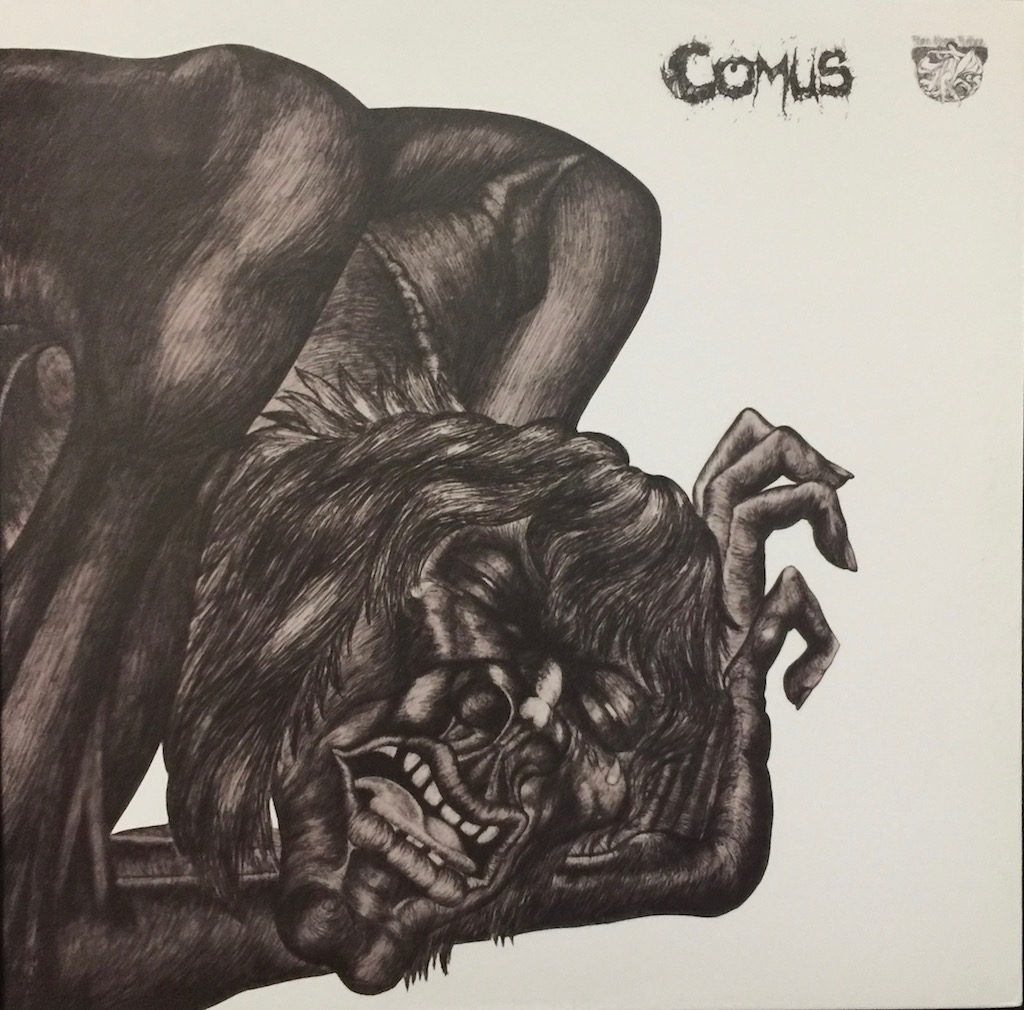

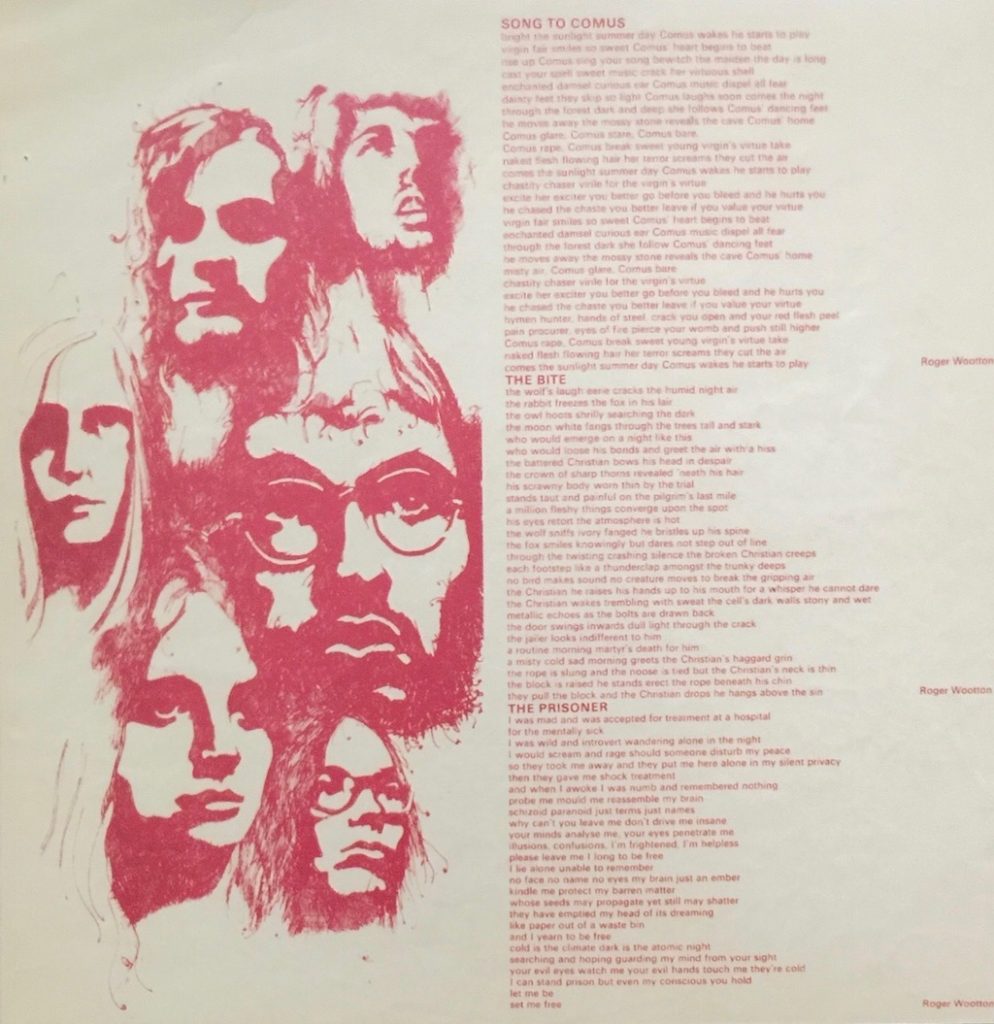

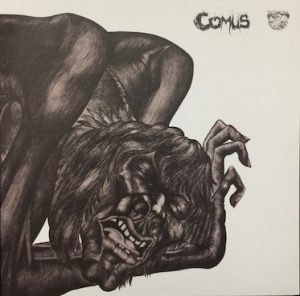

Roger Wootton drew the cover art in ballpoint pen

Given the price of an unmolested original pressing,[1] I opted for a Rise Above Relics reissue, circa 2010, pressed at GZ. Likely taken from a digital file (something I’m trying to verify), the record surfaces of the Rise Above reissue are immaculately quiet, and the nuances of timing, decaying harmonic overtones and spatial character of the original recording are not lost or flattened into a cardboard imitation of music.

It is a high quality reissue, with a two-sided insert sheet, and at the time of the reissue various versions, including a deluxe package, were offered, see note 2, below.

The band released two albums in the ‘70s, but First Utterance is the one with the real following—an album that has been rediscovered by other artists, including Mikael Åkerfeldt of Opeth, a fellow who can appreciate strange dark music better than almost anyone. First Utterance is an eerie, odd assemblage of pastoral motifs, munchkin voices and the sounds of madness, amplified and rearranged for aural consumption.

It may take more than one listen to fully appreciate how intricately woven the textures are here between the vocals, the instrumental interplay and the stark beauty of the thing. It is a very visceral album without sounding too raw, and it all fits together in a way that is impossible to imagine as you are listening to it for the first time. Repeated listening yields greater rewards, but the album remains unpredictable even to those familiar with it.

A first listen will probably leave you a little mystified about what you just heard. Once you get beyond that, you will hear amazing musical versatility, gorgeous guitar tones and the use of strings (violin, viola, and slide bass) in interludes and counterpoints that run from classical motifs to dissonant tones, to frenzied sawing of the bow; the woodwinds tease, offer pastoral themes and almost jazz like excursions; atop it all ride the vocal parts, eerie falsetto voices, choruses and chants, and the tempos vary, with meter measured by hand-struck drum heads and choppy rhythmic beats; if all of this sounds like chaos, it isn’t—it is more like a guided descent into madness.[2]

The contrasts are everywhere on this album, from the dark to the light, the major and minor, the harmonic and dissonant, the intricate and primitive; all of these shifts are occurring not only as the compositions unfold, but at the same time, coinciding with each other- lyrical passages are interrupted by edgy strings and abrupt drum beats or dissonance carries within it a melodic theme.

The album did not sell well when it was first released, but has gained a following over the years as well as a reputation for being a challenging listen.

The group disbanded, reformed and released another album in 1974 but parted ways again until 2008, when they regrouped for a festival appearance. A new album was released in 2012 (Out Of The Coma), consisting of three new songs and an unreleased recording from 1972. Comus maintains a website at https://comusmusic.co.uk.

∞

This is a stunning, strange and at times almost disturbing album that has rightly been recognized as a peak of performance and composition. It defies categorization and has proven enduring, more cherished now by a wider range of music lovers than at the time of its release more than four and a half decades ago.

Part II: Interview with Members of Comus About the Album.

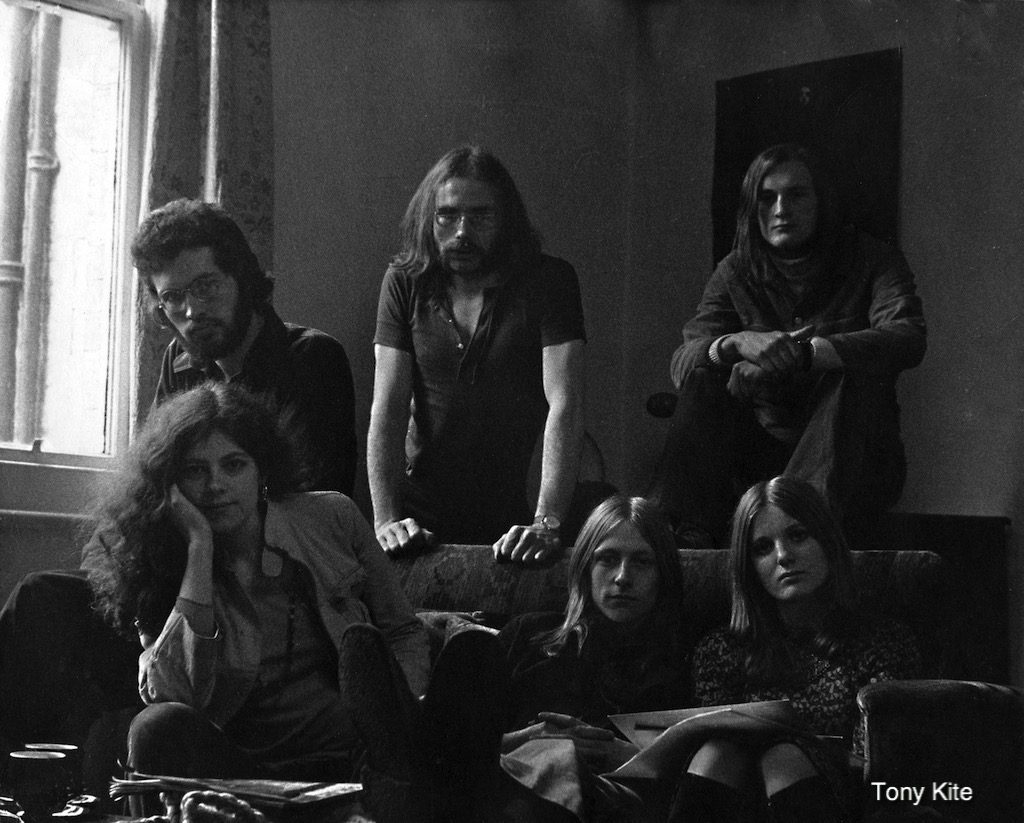

Lindsay Cooper,* Glenn Goring, Bobbie Seagroatt.

back row – Roger Wootton, Andy Hellaby, Colin Pearson

The band was gracious enough to answer a few questions:

TVP:This is one of those albums that sounds like no other. At the time of release, what was the reception, artistically and commercially?

Bobbie Seagroatt (née Watson): Not brilliant, as I think it was just too weird for the market – there was nothing like it really – so that also made it unplaceable, so difficult to review. I think Pye didn’t know how to promote it.

Andy Hellaby: Not very well as far as I can remember.

Colin Pearson: Basically, the student population of England loved us, and, in general, the established media hated us. VIP Music Journalist Penny Valentine felt it was like listening to a cat being strangled. The influential John Peel didn’t like it either, but I think that had as much to do with our political incorrectness than anything musical – we weren’t working class, and didn’t comply to any accepted standards in terms of line-up or what the lyrics were talking about. We guested on his BBC live radio show and I remember him making negative remarks. I always felt our peers steered clear of us because we were just too weird and/or aggressive. It was rather the rock and heavy-rock bands who were more appreciative. I remember Ritchie Blackmore and Ian Paice (I think) visiting us in our dressing room (a white-tiled shower room), to regale us with hilarious recollections of touring in the USA. Years later I was speaking to Ronny James Dio who remembered us from the road, although I don’t think he was with Deep Purple [Ed.Note: Rainbow, Sabbath or Dio? ]at the time. ‘You could play!‘ he said; high praise from a brilliant singer. Commercially the album sold out the first pressing but wasn’t repressed. There were other factors that combined to sound its commercial death-knell, but the others in the band, and our manager, can say more about this, and more accurately.

Glenn Goring: At the beginning as at the end everything about Comus was a slow-but-deep burn. If I remember correctly, the reviews to the album were mixed. Nobody really knew what they were listening to or what the hell to call it. Was it Folk? Rock? R&B? No one had a pigeon, they were shaking their heads in dismay about the whole thing, or find a category that was entirely satisfactory and neat. ‘Acid Folk’ then Psych Rock’ I can’t remember them all. But while the pundits were desperately seeking the correct nomenclature we were gathering a strong audience through live gigs. You could say we were ahead of our time, but in a way that sounds conceited. However, it might explain why there was a delayed reaction to the band.

TVP: If you look deeper into the so-called psych folk movement, there are certain others who fit under the umbrella. But you are pretty removed from the sound of say, a Donovan album or The Incredible String Band. What were you (collectively) hearing that led to this album? Can you identify any “influences” that helped shape what you were striving for on First Utterance?

Bobbie: Roger was the main songwriter at first – see his answers.

Andy: I don’t think there was any collective influence. We all individually had our own influences from folk, classical, rock, blues etc.

Colin: This was highly individual. I was a John Milton fan. I listened to classical music. Outside classical music I listened to the commercial music of the day, principally The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Yes, Pentangle and the British Charts. My fellow band members listened to entirely different stuff, most of which, when I joined the band, I‘d never heard of.

Roger Wootton: We were influenced by the first Velvet Underground ‘banana’ album, though the Incredible String Band were important. There was a strong classical influence introduced by Colin Pearson and Rob Young, who were classically trained. So Stravinsky, Messaein and Shostakovich were in the mix.

Glenn: I was brought up on Nat King Cole, Glenn Miller etc. (who my parents named me after) and tons of musicals around at the time. When I started my playing was influenced by Donovan, then, at art school age 17, where I met Roger, we got listening to a lot of Avant garde Jazz and stuff like Stockhausen. Later, as the band was developing people like Renbourn and Jansch were strong influences on our playing styles but the String Band were there as models of what could be achieved in a kind of orchestral sense. Jefferson Airplane and Beefheart (who we saw at different times, perform in London in the early seventies) were like the Gods descended. Beefheart and the Magic Band, I guess the original lineup at the time, played in this dingy backroom of a pub in a suburb of London called Croydon (it used to be in the county of Surrey but got swallowed up). Roger and I were knocked sideways and speechless by the monumentally atmospheric and quirky performance; totally captivating and original. I could never shake that night off. I taught myself to play slide on top of that dizzying experience.

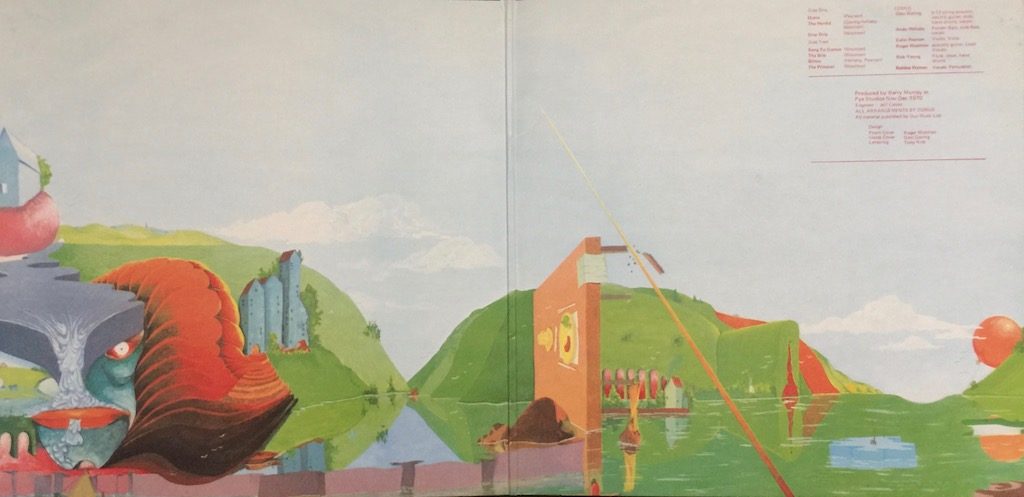

Due to public service disruptions, power was cut to the studio and Glenn “was pretty much forced to paint the majority of the centrefold surrounded by candles”

TVP: Although Andy Hellaby and Colin Pearson are credited (in allmusic) as composers, the band is credited as a whole for all of the arrangements. How did these pieces come together?

Bobbie: We rehearsed them acoustically, and although Roger or Colin had the basics of their songs, we just played / sung what seemed to be appropriate, and had the right feel for the song as we went along. The Herald was a bit different as Roger had the basic verses and ‘chorus’, and then individual solo parts followed each other in sequence.

Andy: We all arranged our own parts to the songs so the overall arrangements came about organically.

Colin: There was an agreement to share the compositions because writing the songs was very much a collaboration of all of the members. Most of the songs grew out of jam sessions. For ‘In Pursuit Of Diana‘ I had the basic idea, some of the chords, and most of the lyrics. Roger did the rest, the amazing chorus was his idea…he just started singing about Diana kicking her feet up! I‘m not sure how I ended up as sole writer… These songs were not put together anywhere near a recording studio. Recording contracts were rare and hard to get. We were told by one producer to go away and play on the road for 6 months and then come back. We were a successful live band, but recording proved to be a problem for us. In retrospect, the album would probably have been much better, and a far more accurate reproduction of our live sound if we had played the tracks in live. As it was, we tracked it, adding overdubs, which, when you don’t have a central rhythm section or a drummer, proved very hard for all of us in terms of feel and timing. Part of the problem was the producer, who didn’t identify the need for a live, collective recording process. We tried to break the songs down into tracks, and, my personal opinion is we were unsuccessful. Our recording engineer Geoff Calver did a great job in difficult circumstances, as he basically, and again in my opinion, took over the producer‘s role.

Roger: A lot was achieved through improvisation….

Glenn: Roger was the most prolific writer in the band. He would dive into his soul and mine the rough jewel-stones of worldly experience, and bring them to the surfacewhere myself and the rest of the band would hone and polish them and bring them fully alive. Often Roger and I would work for hours, just the two of us, re-working chords, slowing down, shortening or lengthening passages accordingly, and every member of the band contributed their own original parts to create the whole.

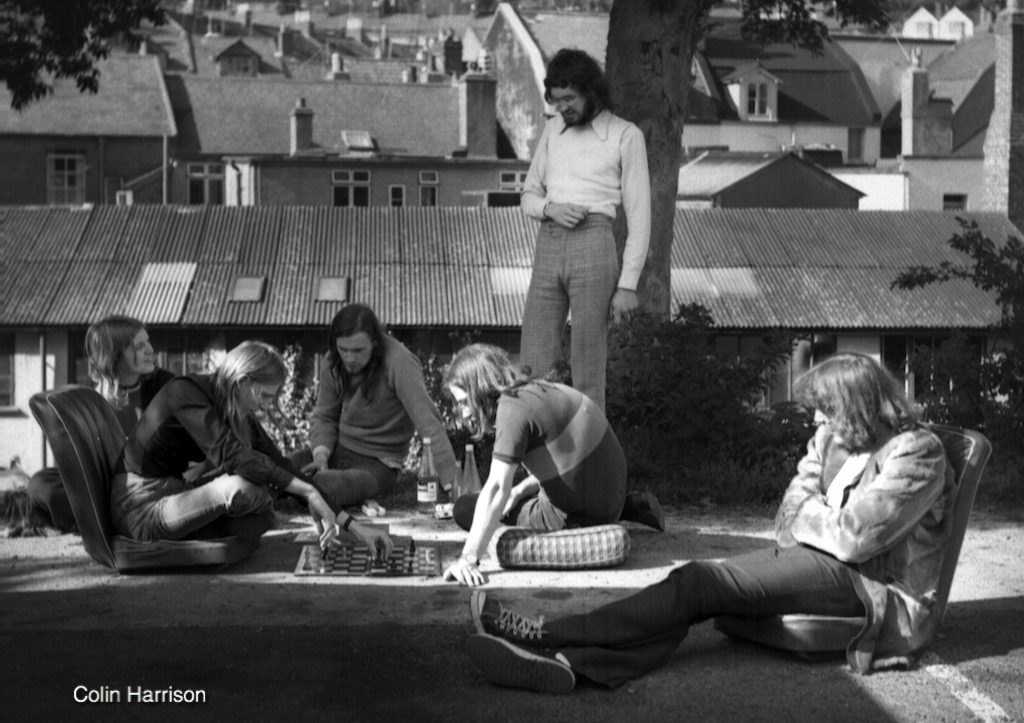

Bobbie Seagroatt, Glenn Goring, Colin Pearson, Andy Hellaby, Roger Wootton (standing), and Rob Young

TVP: Any insight into the recording process- live in studio, how much overdubbing, how many tracks on multi-track, involvement by band in sound as part of production and post-production; recorded at Pye Studios which had by then moved to ATV House near Marble Arch?

Bobbie: We were totally inexperienced at recording, and so weren’t used to hearing stuff back objectively, and so couldn’t make proper judgments about the ’sound’ and could only judge obvious things like bum notes, etc.!

The producer, Barry Murray, was used to recording rock bands with electric guitars, so wanted to put down the bass and drums (!), but I think we just put the guitars down, or maybe guitars and bass, and then put the vocals, and percussion on afterwards.

Roger: We mainly recorded live adding vocals and occasional overdubs afterwards.

Glenn: I always did get lost when it came to those who were pressing the buttons.

TVP: It seems like most of you kept in touch even after the group originally disbanded. What lead to the reunion show? Had any of you been playing or publicly performing together before that show?

Bobbie: Andy and myself (and Glenn to an extent) had been in regular touch since the band broke up, but we hadn’t seen Colin, Roger or Rob Young until a reunion party at our original manager Chris Youle’s house. I hardly recognised them!

This reunion was prompted by the fact that Stefan Dimle (who put on the Melloboat concert in Sweden) had contacted Glenn somehow, and then Glenn told us about it.

None of us had been playing together, although I had had a pretty active musical life since the mid 90’s (NGDE, B So glObal, Drift, The Colins of Paradise), and Glenn had played a bit in duos with a friend. Andy had written synthesizer music for theatrical productions (notable for the Royal Court Theatre in London), so, separately we had being doing things, but not together.

Andy: Not all kept in touch, but our original manager managed to bring us all together not long before the possibility to reform arose.

Colin: I was in Germany working as a producer, and I‘d been living there since 1974, first in Hamburg, then in Berlin. The reunion came about via a Swedish promoter. I‘d stopped playing the violin, so I almost had to re-learn the instrument. Not easy!

Roger: In 2007 we were contacted by the Stefan Dimle for the Melloboat Festival in Sweden. Michael Ackerfeldt of Opeth was a friend of Stefan, who had asked Opeth to play the festival as well. Mikael said that they would only play the festival if Comus were persuaded to reform and do it as well.

Glenn: It was several years after I left the band that I went back to performing, first in an electric ensemble called The Hollow Men and then part of an acoustic duo playing folk/flamenco pieces of our own composition. Andy and I were regularly in touch since Comus split. Lost touch with Bobbie for a time but we were in contact off and on. Colin and Roger had disappeared off the map so it was a very interesting moment when we had the first reunion party at Chris and Gess Youle’s place near Deal on the south coast. There was a lot of doubt about re-forming. I remember saying to my regular barber, who asked me why Comus had not got back together. I said, there was more chance of seeing God than a Comus re-union. In fact, we were playing together longer the second time round as a band reformed than the original band and I had kept in touch before the so called reunion gig on the Melloboat.

TVP: The Rise Above reissue of First Utterance is very nice. How did that come about?

Roger: Lee Dorrian, who runs Rise Above is also a major fan and wanted to re-release it. He attended the Melloboat Feastival at which we played in 2008.

Glenn: Thanks to Lee Dorrian for his belief and interest in the band.

TVP: Rise Above also released your 2012 album, Out of the Coma.Tell us a little about that.

Bobbie: I was contacted by David Tibet of Current 93, who was a massive fan of Comus. Lee Dorrian of Rise Above contacted us for an interview, and as a result, we split the ‘Out of The Coma’ album between Lee Dorrian for the vinyl, and the CD on David Tibet’slabel.

Colin: I think Bobbie, Roger or Glenn might know more about this. I mostly remember travelling between Berlin and Banbury, UK. Jon Seagroatt did a fantastic job putting the album together.

Roger: Lee Dorrian, who runs Rise Above is also a major fan [as mentioned above].

Bobbie: Jonny (my husband) recorded the whole thing, mixed and mastered it. A lot of it was recorded live in a concert hall at one of the places Jonny works, (teaching music technology), and vocals / flute / soprano sax / additional percussion etc., were overdubbed later in J’s studio here. He’s pretty experienced at all this as he’s been recording since the 90’s, and did most of the recording, arranging, mixing and mastering for the stuff he and I have done together in the bands

“B So gLObal,” “The Drift’ and “The Colins of Paradise,” and his own bands previous to that.

TVP:Any further touring or public appearances scheduled in the near future?

Bobbie: We are still offered concerts, but everyone has to be on the same page in a band, and this seems very difficult with Comus! Some are keen to do them, some are not. “It’s complicated,” as they say…”.

Glenn: “More chance of seeing God…”

TVP: I’ve found that younger people could care less about how a piece of music is categorized- and in some ways, are more open minded about music, even if they don’t necessarily know the history. Are you heartened by the younger generation’s agnosticism toward genre?

Bobbie: Most certainly! I love the fact that young people are so admiring, and are influenced by Comus… I think that there is so much music available, and that younger fans can pick and choose so easily, they don’t have to listen to a whole album and decide whether they like that particular genre – they might just hear a track and decide they like it, whatever it is, and wherever they found it.

Colin: Do you mean “couldn’t care less“? If so, then yes. Like books, genre is a marketing label. But, there is one thing I would say. Today, anyone can write anything and release it, just as anyone can record anything and release it. Artistically this is progress, but it also means real musical gems are lost, buried beneath an enormous pile of musical and literary indulgence. As a consumer, you really don’t know where to go, or know what you’re getting. Artists andwriters today have complete freedom. People used to say the cream rises to the top. Today I think some of it goes sour before it gets there.

Roger: Yes, I was amazed to have such a young following. The age range of fans at gigs is from 15 to 60. I think it is because the music is so original and doesn’t fix itself in the time it was recorded and the instruments are acoustic so it doesn’t suffer from sounding old fashioned.

Glenn: Is this true? If so, being honest, I don’t really care. How long will stand, a stick in the sand?

∇

The interviews of band members in so many ways reflect the recording itself- different viewpoints, different backgrounds, melding into something that coheres but reveals the individual and very unique contributions of each member. My thanks to the band for their insight into what is and will remain a high water mark of eclectic, genre-defying music.

Bill Hart

Austin, TX.

August 2018

_________________________________________________

[1] Released on the Dawn label, an imprint of Pye for underground and progressive music. See https://www.discogs.com/sell/release/899537?ev=rb&condition=Near+Mint+%28NM+or+M-%29

[2] Some CD reissues, such as the current Esoteric Recordings release, include bonus tracks, such as “All The Colours of Darkness.” The Rise Above LP consists only of the tracks of the album as originally issued, although a deluxe package offered a 10 inch single along with a reissue of the original LP. Music on Vinyl (MOV) more recently reissued the vinyl as well.

*Lindsay Cooper did not perform on First Utterance, but joined the band shortly thereafter and was known for her association with Henry Cow and National Health as well as Comus.

Photo credits: band interior shot with Lindsay Cooper by Tony Kite; carpark photo of band by Colin Harrison, both by arrangement through Bobbie Seagroatt.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.