As usual, I came to this party late. While the States was enjoying a folk revival in the mid-sixties that led to a range of new sounds from artists like Bob Dylan, the UK folk scene developed a little differently. Joe Boyd, who is credited with helping Dylan “plug in” at Newport, was working the London club scene with bands like Pink Floyd and managed to sign this new folk group—Fairport Convention– to capture some of that American folk sound: what resulted was eventually quite different, and led to a series of albums that saw the band develop a far more distinctive sound based on traditional English folk music.

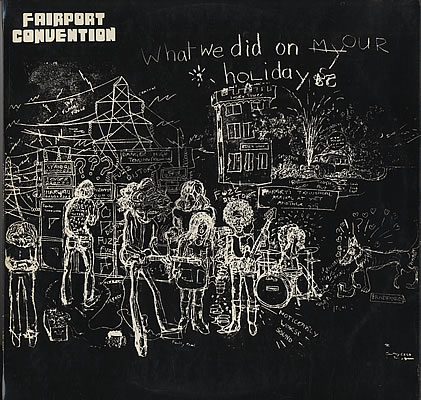

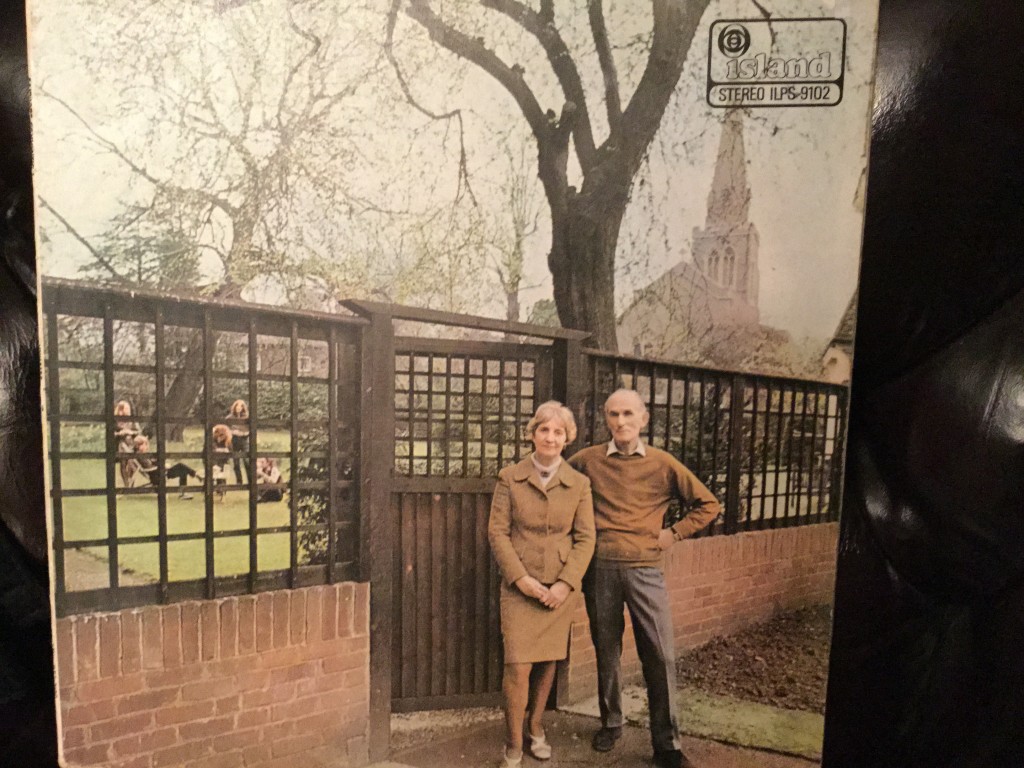

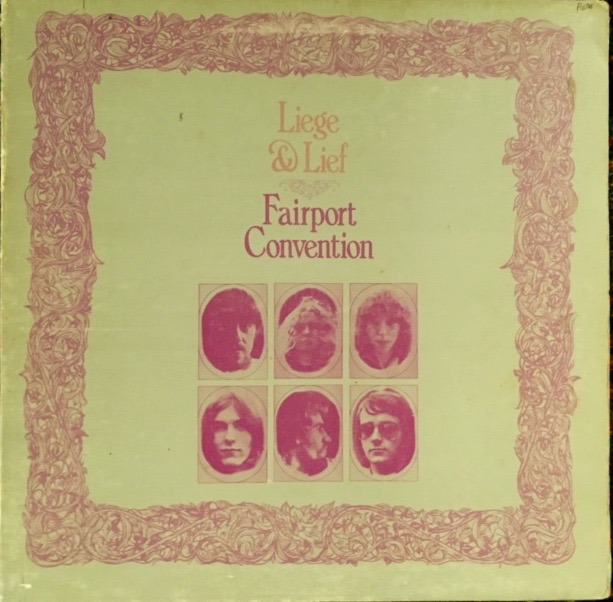

The band signed to Island early on (their first, self-titled album was on Polydor). What followed was a series of albums that defined a special place in the coalescence of “nativist” (in the sense of perpetuating a tradition) music, which evolved from an American “sound” to one that was not only distinctly English, but altogether unique in style: a young, but highly-skilled Richard Thompson wrote and brought a sophistication to his guitar playing that belied his years; coupled with the heavenly voice of Sandy Denny and a group of talented band members, three essential albums resulted: What We Did on Our Holidays, Unhalfbricking and what is considered to be their peak work, Liege and Lief.

In the midst of these records, a road accident killed the drummer and Thompson’s girlfriend, injuring several other members of the band. Although Unhalfbricking may have been a popular album in the UK at the time, Liege and Lief, the album that followed (the road accident) is, in retrospect, considered the more influential, because it reflects the group’s almost complete transition away from an “American” folk orientation. Denny is often credited with this shift in focus. She left Fairport shortly after Liege and Lief to embark on a variety of experiments, including solo work, before returning to the band in 1974. Sadly, she passed away in 1977 at the age of 31.[1]

Thompson went on to a long career as solo artist after departing from Fairport in 1970 and the band went through various personnel changes thereafter.

At least that’s the textbook version of the story.

I wasn’t much of a “folkie” growing up in the States in the sixties (I was only ten years old in 1965), though as time went on, I certainly became familiar with some of the traditions- the work songs, the protest songs, and the lilting, story-telling ballads. When I finally got around to hearing some of the Fairport records from the Denny-Thompson era, I was struck by something that transcended all of the elements with which I was already familiar; there was something haunting about Sandy Denny’s voice, and the band wasn’t just strumming through another tired old ballad. The key to this record, and the band’s sound was something that gave the whole band an otherworldly quality: Denny’s voice was often characterized as “ethereal,” but it is more than just that voice; and it wasn’t just well-played folk-rock, either. Instead, I think it was raw talent, leavened, tempered and forged into something different- my guess is that the band members were changed by everything they went through in very short time.

I asked Joe Boyd,[2] who produced the group, to describe what it was like in to work with the band during this, their creatively richest period and what he thought led to the evolution in their sound:

Fairport Convention – like many groups in that era – developed rapidly over the course of their first three albums. The dialectic of Richard Thompson and Sandy Denny was driving them towards becoming a very original and successful band when tragedy struck. Their first impulse was to disband, but decided to carry on while vowing never to play the repertoire they had developed with drummer Martin Lamble, who died in the crash. Music From Big Pink was a huge influence during that traumatic spring of 1969. It both barred the way to any further exploration of American roots music – how could a bunch of English kids possibly compete with that? – and inspired them to look for their own roots in the traditions of the British Isles. This new repertoire was driven by a combination of Sandy’s experience in folk clubs, Ashley Hutchings intense research, the addition of ace trad fiddler Dave Swarbrick, Thompson’s blues-avoiding rock guitar virtuosity and the discovery of strict-tempo dance-band drummer Dave Mattacks who steered them clear of rock clichés.

–Joe Boyd

When you take in this body of work now, it is all the more remarkable that the three albums- What We Did on our Holidays, Unhalfbricking and Liege and Lief were released within a single year, from January through December, 1969, with the deaths, injuries and marked evolution of their style all occurring within this remarkably brief period.

Among my copies are early UK Island pink labels and pink rims; as seem to be typical of my experience with Island’s output during this period, the pink labels are warmer and sound less “reproduced” but the pink rims are quieter.

If you aren’t familiar with Fairport Convention, at least buy Liege and Lief on an old Island UK pressing. These records aren’t terribly expensive. I think you’ll find, as I have, that this leads you to tap into more undiscovered, rich veins from this era of music-making in England. That so much of this material was first recorded on Island tells you just how influential that label was and remains.

[1] Before her untimely death, Denny managed to squeeze in a duet on Led Zeppelin’s ‘Zoso” album (a/k/a LZ IV) as well write “Who Knows Where the Time Goes” (1967), later covered by Judy Collins with great success.

[2] Boyd’s rather remarkable life included organizing European tours of blues and soul artists such as Muddy Waters, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, handling the “sound” at the 1965 Newport Festival (where Dylan ‘went’ electric) and operating the UFO Club, where Pink Floyd developed their sound. His book, White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960’s recounts much of this in detail and is a fascinating read: http://www.joeboyd.co.uk