Hooker ‘n Heat by Rebecca Davis

Known for their musical dedication to primal electric blues, 1960s stalwarts Canned Heat are also noteworthy for their support of actual blues men. In various settings, they frequently provided musical backing – and commercial connections – for the elders who had inspired them artistically. Canned Heat founder Alan “Blind Owl” Wilson had started his recording career this way, accompanying Delta legend Son House on his 1965 “comeback” for Columbia. Guitarist Henry Vestine had been involved in the rediscovery of Skip James, and vocalist Bob Hite was a veritable encyclopedia of musical information, traditional blues lyrics, and lore. All three were keen record collectors.

Later blues men associated with Canned Heat included Albert Collins, Gatemouth Brown, Sunnyland Slim, and others. As well as providing public exposure for the older musicians, these kinds of projects were immensely satisfying for the members of the band. The high point of all this remains Hooker ‘n Heat, recorded in May 1970 with John Lee Hooker and a modified version of the “classic” Canned Heat lineup.

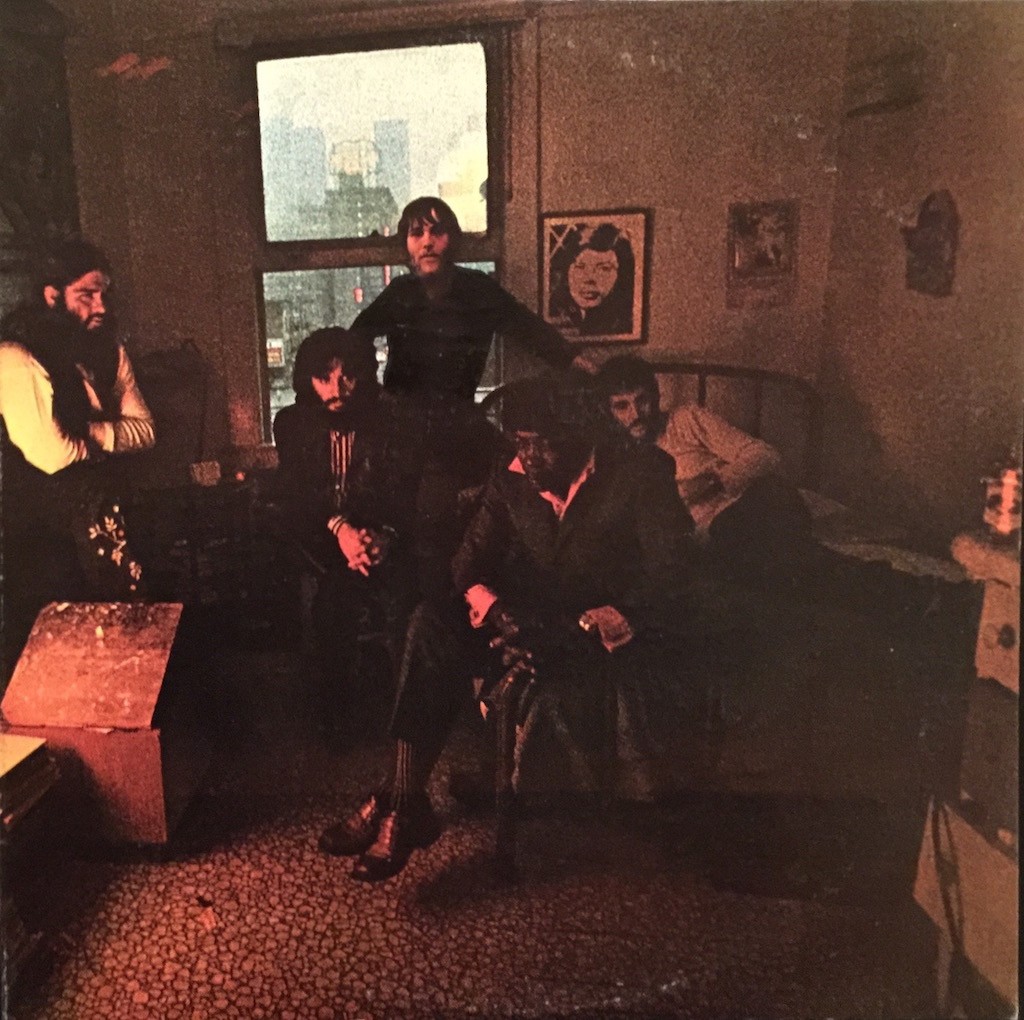

Bob Hite took a pass on Hooker ‘n Heat so that Hooker’s vocals could claim primary attention. The remaining core of the group consisted of singer/harmonica player/guitarist Alan Wilson, guitarist Henry Vestine, and drummer Fito de la Parra. They were supported by bassist Antonio de la Barreda, whose Canned Heat career did not last particularly long. The band usually featured Larry Taylor on bass, but at that time he and Vestine were not getting along.

Though a fine vocalist in the “blues shouter” mode, Hite showed his devotion to pure blues over showmanship by stepping back into the control booth. His voice can be heard offering encouragement and banter between songs. Wilson shines up front along with Hooker, their synchronicity making the album a truly collaborative effort. It is a far cry from the awkward, cliche-laden “special guest” appearances so often used as commercial props. This was, rather, a true meeting of musical minds, with the rest of the band laying down the groove in a quintessential support mode.

For Alan Wilson, the creative genius behind classic-era Canned Heat, the recording sessions became the expression for a musical affinity of uncanny, spiritual depth. Hooker’s perspective was well documented by Charles Shaar Murray in 2002, in the book Boogie Man: The Adventures of John Lee Hooker in the American Twentieth Century. He makes it clear that this feeling of musical kinship was mutual, exalting Wilson’s intuitive blues sensibilities that enabled him to effectively accompany Hooker as few others could. And even beyond, Hooker seems to have connected directly with Wilson on the heart level.

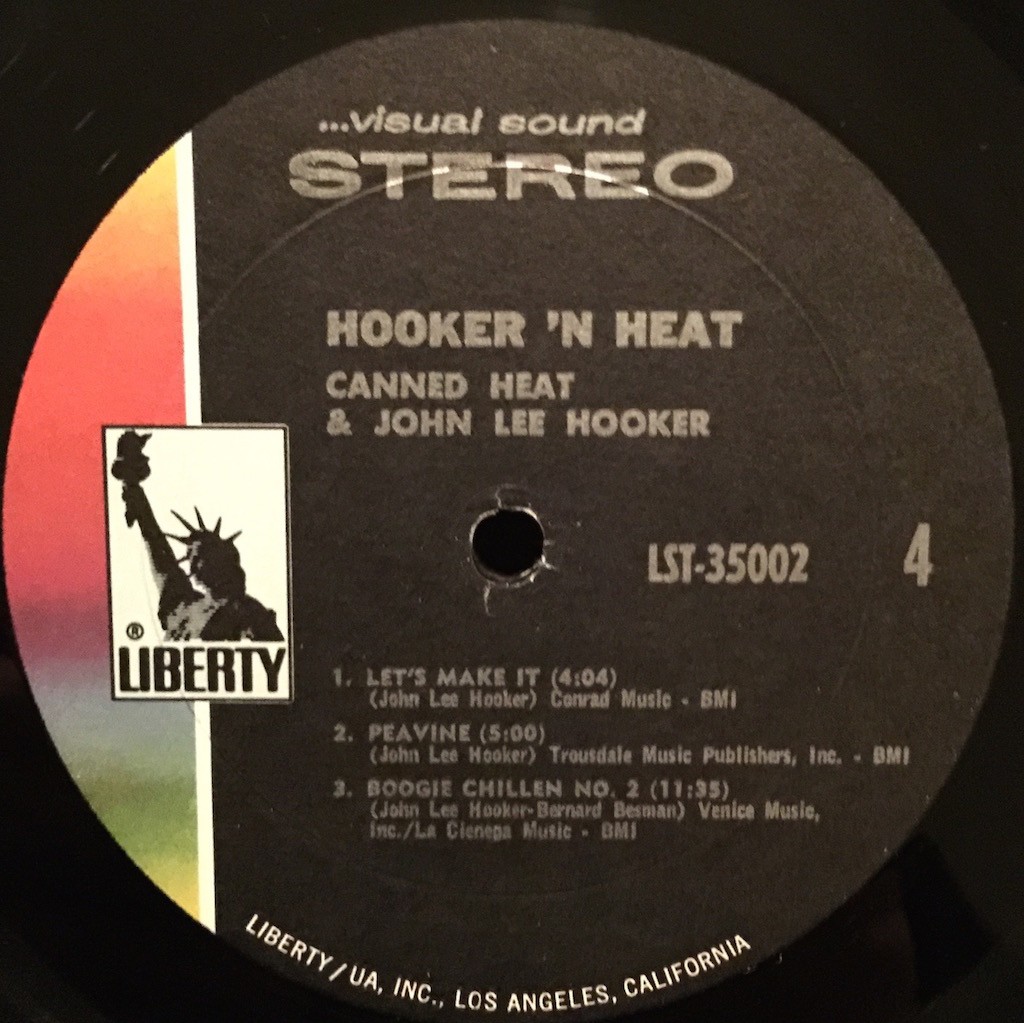

The release ended up being a double album, with the entire first LP side being taken up with Hooker solo performances. Here, then, is Canned Heat’s agenda: first and foremost, they wanted their fans to hear John Lee Hooker. Alone, with his electric guitar, is how Wilson wanted Hooker to be presented. In 1968, he told an interviewer, “Perhaps a forward stage of evolution is getting into patterns based on just breathing. And not that rigid. So that’s one thing – that’s actually why I think soloists have it over the bands, because the patterns are more flexible, because people don’t get hung up trying to follow each others’ patterns. Guys like Hooker.”

Wilson’s feeling of breathing music permeates his harmonica playing, which is introduced partway through side 2 of the first LP. We also hear him on piano briefly, on “Bottle Up and Go” and “The World Today”. These are of course interesting, but he is heard to best effect on harmonica. This and guitar served as his primary instruments throughout his career. Here, his wailing fat-toned harmonica interplays with Hooker’s menacing voice to generate one of the deepest blues atmospheres ever committed to vinyl.

The band is featured on the second record which culminates in a rollicking eleven-minute long boogie. It was based on John Lee Hooker’s hit debut, “Boogie Chillen”, released in 1949. Interpreted in various recorded forms such as “Refried Boogie” and “Fried Hockey Boogie”, it had already become a staple of Canned Heat’s live shows by 1970.

Hearing the blues, the banter, the boogie, it can be hard to imagine what Alan Wilson was going through at the time. Unbeknownst to listeners, after the songs wound up for the day, Alan Wilson was returning not to a comfortable home but to the psychiatric ward of a local hospital. For years, he had suffered from extreme depression, and after a recent suicide attempt had been coaxed into in-patient care.

Canned Heat manager Skip Taylor recalled that the recording studio was in close proximity to the hospital where Wilson was checked in. And the timing was not completely coincidental. Taylor and Canned Heat had been pushing to record with John Lee Hooker for some time, both for artistic reasons and for Wilson’s sake. “That was something that we thought would bring him around,” Taylor later remembered, “because it would give him something… I mean, there he was, playing with an idol.”

Much as these recording sessions must have given Wilson an artistic lift, it couldn’t possibly resolve all of the personal issues that had been tormenting him. His depression was entwined with an insomnia problem and abuse of barbiturate drugs. Some of these were obtained off the street or via other illicit means, and Wilson would have had no way of knowing their strength. His body was found, with traces of barbiturates in his system, in a wooded grove near Bob Hite’s house. It was a devastating, but not completely unexpected, blow to the band. Wilson had been considering leaving Canned Heat for some months, and was reportedly tired of touring; his passing would provide a tragic, permanent escape from the rock star lifestyle that never quite suited him.

The 27-year old Wilson had kicked off his recording career by accompanying House, and it seems fitting that his magical sessions with Hooker serve as his swan song. His career is bookended with the bluesmen who had rooted him musically, the first representing the acoustic, rural Delta blues, the final representing the transformation of that tradition into the stomping electric boogie, perfected in cities like Detroit and Chicago. Canned Heat took that tradition and brought it into the rock and roll era, updating it for psychedelic audiences.

After Wilson’s death, Canned Heat appeared with Hooker occasionally during live shows. One of these, featuring a lineup with Bob Hite’s brother Richard on bass, was recorded for the 1981 album Live at the Fox Venice Theater. After Bob’s death, yet a different permutation of the band recorded with Hooker on his 1989 “comeback” album The Healer. Hooker also guested on the occasional Canned Heat record, having sporadic contact until his death in 2001.

Since Bob Hite’s 1981 death, the band has been led by classic-era drummer Fito de la Parra. Members segueing in and out have included Henry Vestine until his 1997 death, legendary bassist Larry Taylor, guitarist and Woodstock alumnus Harvey Mandel, and many other vocalists, guitarists, and keyboardists. Throughout deaths of various band members, personal tragedies, and the ups and downs of musical trends, Canned Heat has persevered. They boogie on, continuing to record and perform to this day.

Rebecca Davis

© 2015 Rebecca Davis

◊

In 1999, De la Parra released his autobiography, Living the Blues; more information on this and current band activities can be found at CannedHeatMusic.com.

Alan Wilson’s life and death was documented in the 2007 book Blind Owl Blues by music historian Rebecca Davis. Her website is at BlindOwlBluesBook.com; all quotes herein are from Blind Owl Blues.

Fans will also want to keep up with the latest news on Harvey Mandel, who has been battling cancer. Updates and donation information can be found at HelpHarveyMandel.com.