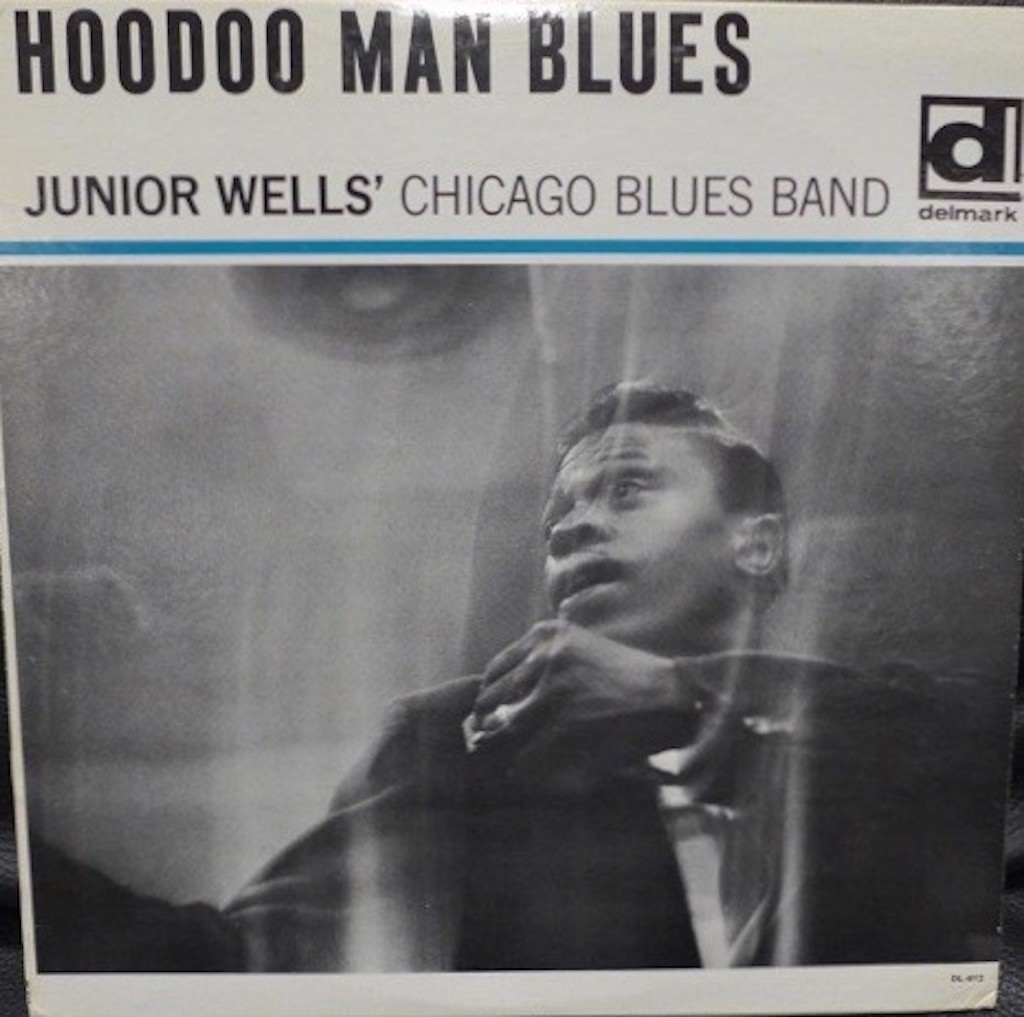

I had the privilege of writing an essay on Hoodoo Man Blues for the National Recording Registry of the U.S. Library of Congress. (You can find the text of the essay here, along with a link to the National Registry where it is officially published).

Bob Koester, the founder of Delmark Records (which released Hoodoo Man Blues) and producer of the album, was gracious enough to provide a first-hand account in that essay. (His views lent a far more authentic and interesting voice than any third-hand account I could write fifty years after the fact).

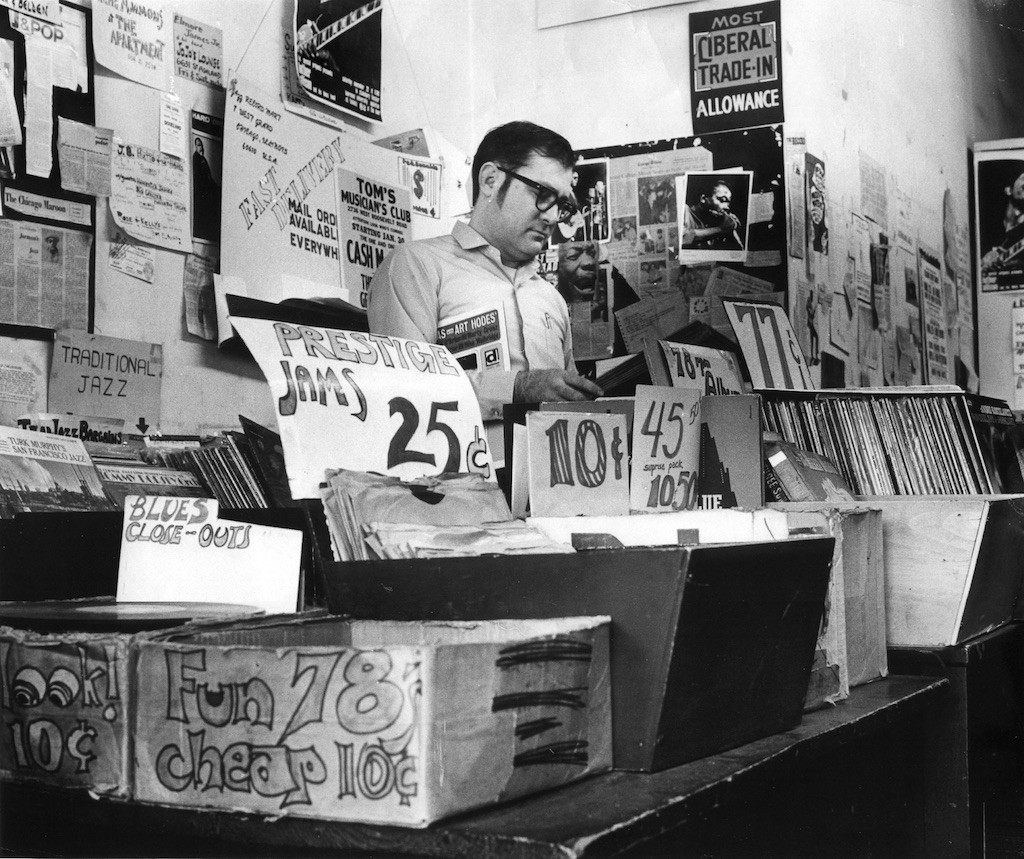

Koester is a virtual encyclopedia of the blues, having lived, worked in and contributed to this field of music for over sixty years. He is a vital part of that history.

What follows is an interview with Bob Koester, about the blues, the Chicago music scene in the day and a look at the emergence of the electric blues and where it is going. We owe a debt of gratitude to Mr. Koester for keeping the flame alive all these years.

Bill Hart

August 14, 2015

This interview is not part of the Library of Congress essay and does not represent the views of the Library of Congress.

(Images courtesy of Delmark Records and Bob Koester)

You founded Delmark in 1953. What got you into the “record business” and was Delmark always blues-oriented from the start?

BK: No, my main interest was traditional jazz (I hate the word Dixieland – it always seemed slightly racist to me for some reason). The first Delmark (#101) was by the Windy City 6 (named for the type of traditional jazz they played). They were in St.Louis. A few months after 101’s release they got a new leader and changed the name to the Mound City 6. This didn’t help sales. I then recorded trombonist Sid Dawson and acquired some masters by the great George Lewis band of New Orleans, which really helped us get distribution because Lewis was touring all over the place. I started recording Speckled Red and Big Joe Williams and J.D.Short soon after and printed 10″ LP covers for Red and Joe’s albums but over one weekend the industry discontinued 10″ LP’s which were standard for pop, jazz, etc. and switched to 12″ which had been mainly for classical and show biz.

When I characterized Delmark as one of the “original” Chicago blues labels in the context of “electric blues,” you pointed me to the long history of blues coming out of Chicago from the dawn of recorded music.

BK:Well, not quite the dawn of recorded music. Partly because I don’t think there were recording studios in Chicago until the late teens or early 20’s. Before Mamie Smith the only black artists who were recorded were spiritual quartets and a very few orchestras. Paramount was one of the more famous labels (based in Milwaukee with a Chicago-based publishing house) and Okeh. There were also significant records produced in Chicago by Lester Melrose for Victor and Columbia (i.e., Bluebird, Vocalion, and Okeh). Okeh was indie until 1926 when it was sold to Columbia. Both had studios in Chicago at the time. As did Victor.

Chicago (and Milwaukee), being closer to the south, was where a lot of down-home blues were recorded from the early 20’s. So when electric blues came along that’s where it mainly happened.

Electric guitar and electric blues bands did exist elsewhere. But the two guys who handled blues for the 3 major labels (Victor,Columbia and Decca) didn’t appreciate the blues band sound. Neither did Chess until Little Walter recorded for another label (currently on Delmark #648).

Some of the blues-oriented labels mentioned in the Registry essay about Hoodoo Man Blues were actually started by former employees of yours.

BK: That’s right. Alligator Records was formed by former Delmark employee Bruce Iglauer. Michael Frank, who formed Earwig, worked at the Jazz Record Mart in Chicago, which I also own. A British chap whose name I forget, Peter something, had a reissue label when he went back to England.

At the time you started Delmark, was the “electric” style in full swing or did that really come later?

BK: No, I heard some electric blues bands in St.Louis and East St.Louis in my early days. One of the problems was that the sound level of acoustic and electric instruments was often not well-mixed live. I suspect Big Bill, Memphis Minnie and others of the older school probably had blues bands at their main gigs. Just that Lester Melrose and Mayo Williams [both notable early publishers of the blues] didn’t like that sound. It probably took some time to get it developed at clubs. Muddy and Wolf were great at balancing their sidemen’s volume levels. I saw Muddy when I first came to Chicago in ’58 and realized how great that band sound could be.

It’s interesting that it took the Brits to rediscover American “electric blues.” The American revival, for the most part, seemed more focused on the folk blues at first.

BK: Yes, that’s true. I think that’s partly because folk music centered in New York and they didn’t have blues bands there. Not much of a blues scene: Leadbelly, Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, Jack Dupree, and very few others. For what it’s worth, the “skiffle” movement in the 1950’s in the UK, which was heavily influenced by New Orleans jazz, was at the root of early UK rock and roll, including the early Beatles. The U.S. interest in blues, and the revival in the early ‘60s, was definitely more focused on folk and rural blues.

You explained to me that Hoodoo is actually unique as an LP for several reasons.

BK: Hoodoo Man Blues was the first time a working blues band went into the studio to record an LP. Previous LP’s were either reissues of single 78’s and 45’s or were soloists, duos or studio groups that did not work together regularly. There was a Muddy Waters At Newport LP on Chess with his regular working band but that was a “live” record, not a studio recording. The other Muddy’s were mostly collections of singles or studio groups usually involving Willie Dixon who was never a member of his working band.

Why did you choose not to include or release any singles from Hoodoo?

To issue a 45 without joining the payola scene back in the day was a waste of money. We actually did press a 45, sold very few and gave the rest away. Another reason is we wished to give the artist freedom beyond limits of a 3 minute single.

You bought the Jazz Record Mart from Seymour Schwartz in 1959 and still operate it today. Was it mainly 78’s and singles then? Who was buying blues records back in the early ‘60s?

BK: I had to move the store to make room for the Auditorium Bldg. Offices I dropped Seymour’s name when we had to move.

We sold old 78’s and LP’s and a very few 45’s. I issued Big Joe’s 602 while we were still there and was surprised when it sold 700 copies the first year. It helped that he showed up in Chicago right after the release date and worked a few folk clubs.

The folk thing was on and some folkies also liked country blues and, if in Chicago, eventually got into electric blues.

It seems like, apart from a hardcore segment of blues aficionados, the mainstream popularity of blues comes and goes in cycles, and each time, something new or different is added by those interpreting it.

BK: Well, the white artists come along and have their following, I think, because young Caucasians can more readily identify with them – then they get into black artists.

And that hardcore segment has grown considerably over the years.

I’ve watched that 1972 film, Chicago Blues, which captured the club scene at the time and contained some memorable performances. Can you describe the scene today?

BK: It’s pretty much the same except that several of the clubs are in white neighborhoods and can pay the artists better money than the remaining ghetto bars. B.L.U.E.S., Kingston Mines, Rosa’s plus, always, several others on the North side do very well. The easy access for visitors has made them a tourist attraction and I think some visitors become blues fans after visiting the clubs.

Some of my favorite recordings are very simple- not polished productions with overdubs. I’d rather hear something that sounds visceral, and captures the emotional essence of a performance than some slick,” flawless” production that loses the ‘soul’ of the music and performance in the process. Maybe that’s one reason why traditional blues is so appealing.

BK: I agree. With modern recording techniques we can perfect any recording but, at least at Delmark, we prefer to think we are focusing mainly on the basic scene. We’ve added horns (and I prefer jazz horns to most blues horns), almost always at the request of the artist and often on only a few tracks. But we come up with, I believe, with what the group would sound like in a club. And some bands do have horns. (First time I saw Otis Rush he had a trumpet, alto, two tenors and a baritone sax. The horn player on his early classics left for a lifetime gig with Duke Ellington).

Hey, Big Joe Turner, one of the greatest bluesman of all time (and an artist who introduced a lot of people to the blues) worked with jazz musicians all the time.

And Ransom Knowling, the great bass/tuba player on so many Lester Melrose dates did his first recording before he left New Orleans, in the ‘20s for Columbia with Papa Celestin’s jazz band.

Are there any great blues LPs or singles that are worth seeking out that are below the radar but aren’t so rare that they are crazy money today?

BK: One of the most unappreciated artists in blues history and a major influence on B.B.King was born in Africa: Peter Joseph Clayton (bet there was a missionary involved at his birth). Not well known or appreciated by whites, perhaps, because he didn’t play a guitar, but was a best selling artist. B.B. told me once he carried a Clayton tape with him on the road. Oh yes, his best known recording name was Doctor Clayton. I think standup singers are generally under-regarded by whites.

Any thoughts about an autobiography? You’ve been a vital part of the Chicago music scene for 60 years and not only have a huge amount of knowledge, but you’ve lived it.

BK: Northwestern U. asked me to do one and I work on it once in a while. I think I’m up to the time I moved from St.Louis. [to Chicago].

∫