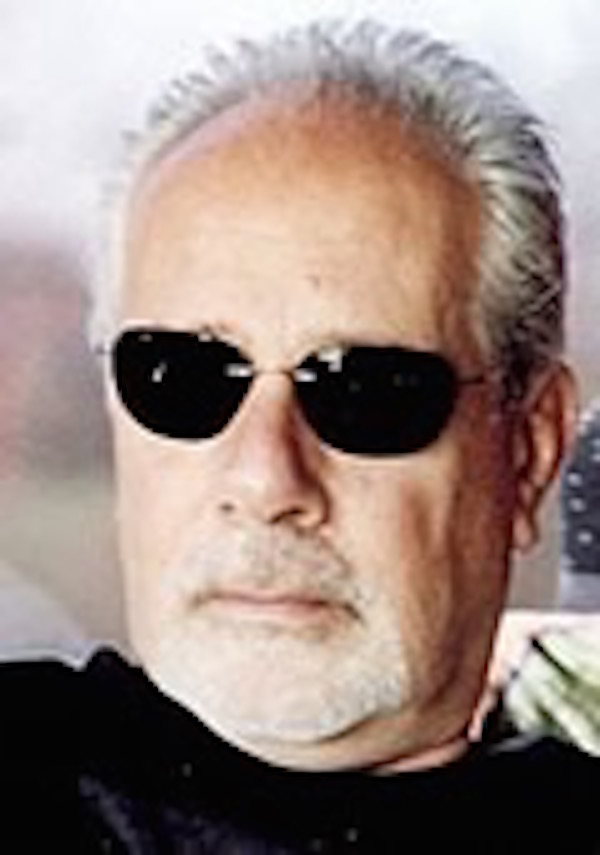

Skip Taylor, who managed Canned Heat during the band’s classic era, produced the albums discussed here and is still working with them today, was gracious enough to share some insights. Skip’s story is itself the stuff of legend, as you will see:

How did you get involved with Canned Heat?

Skip: When I joined the band as manager, and eventually got involved in producing their records, I knew nothing about the blues; I was a rock music guy; the band was really detached from the modern rock scene for the most part, except for Bob Hite, who worked in a record store, collected records and was more plugged in to the current music scene than the others.

I helped start the rock division at William Morris Agency. I had a friend, Gary Essert, who was the head of film school at UCLA. His students included Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek, as well Frank Cook (the first drummer for Canned Heat).

Gary told me “there are these two bands that are getting a buzz- they are playing at a frat party- you should hear them- it was The Doors and Canned Heat. I went and was blown away by both bands- Morrison was reciting poetry to minimalist music. The Doors were “preppy” compared to Canned Heat; I heard the potential of Canned Heat, even though I wasn’t really versed in blues history.

Over the next couple days I had both bands in my office- The Doors already had demos- so I made a deal for them with Jac Holzman of Elektra. I also started working with Canned Heat.

How did you go from agent to producer/manager?

Skip: I left William Morris with John Hartmann who was in Morris’ television department. John was responsible for booking talent on TV and was also interested in this “new” music.

At the time, William Morris was pretty formal and stodgy. The company had no interest in pursuing the San Francisco bands that I was focusing on; bands that were starting to drive the rock/psych/blues movement in the mid-‘60s.

I got called into the CEO’s office one day- I knew he already took a dim view of my interest in the San Francisco scene, and wasn’t eager to put any resources into pursuing those bands or setting up an office there.

When I walked into his office after being summoned, the CEO had nothing on his desk but a couple of joints.

I asked him, “What are those?” He said “we found them in your desk over the weekend.” I quit on the spot. Aside from the intrusion of routing around in my desk over a weekend, it was pretty clear that we weren’t on the same path.

John Hartmann left with me and we opened the Kaleidoscope, a “Fillmore”-type club in L.A. in the old Moulin Rouge location on Sunset Blvd.

I had the sense to include what later became a common clause in the contracts I had done with talent while I was at William Morris; a “key man” clause that allowed the artists to terminate if I left the company. Many of those artists eventually followed me.

Canned Heat and Buffalo Springfield played at the Kaleidoscope regularly, as did The Seeds, Spirit and Kaleidoscope.[1] We were making record deals and producing as well as running a venue. Big Brother (with Joplin) played four shows in two days at the club. But, we were also having “issues” with the owner of the venue, who wanted half the action. (He was the kind of guy you don’t refuse). By doing double shows, we could keep our share, but I couldn’t devote all my time to the club, with management, production and deal-making duties as well. John stayed with the club, and I shifted to management and producing full time. John and I remain friends to this day.

So, what happened with Canned Heat?

Skip: “On the Road Again” went to #1 in every city even though that was not reflected on national charts; the band was hot, and knew how to play. These guys were really skilled musicians, and they were playing all the time. When Boogie With Canned Heat took off commercially, it gave us the chance to focus on what we were doing. The band was aiming for what they considered the big time- their target for success was the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, which was a great band, and successful, but not as successful as some of the big rock acts became. I had my eye on that kind of success for the band. I may not have had the deep knowledge of blues that these guys did, but I knew how to help them become more commercial while staying true to their blues roots. “On the Road” was proof of that. There was huge “crossover” beyond the traditional blues audience. As the band continued to develop, its fame in those days spread far beyond their expectations- they never really thought in terms of being “rock stars” but they did achieve that level of recognition in their heyday.

What did you do to achieve that?

Skip: These guys were already top players. The question was getting their sound on record. We spent a huge amount of time in studios, experimenting; we tried out different studios, just to hear how the songs sounded. It wasn’t like these guys needed to improve their playing; it was more about how we could record it in a way that captured their sound on a recording. And, they were constantly touring.

Can you give us an example?

Skip: “Let’s Work Together” [from Future Blues]- sounded best as a mono mix which had real “kick” so that’s how we left it after much experimentation. (Note that this track is in mono even on the stereo album). As a side note, Wilbert Harrison wrote the song a number of years before, but not much had happened with it; we had recorded it and were about to release it when Harrison’s, the original, started getting airplay; Bob Hite wanted to stop our release out of deference to Wilbert, so Liberty held off releasing the single in the States for several months.

I’ll bet the record company wasn’t happy….

Skip: Liberty Records actually gave us a lot of latitude. We were successful. And, we were able to release these longer tracks, like “Parthenogenesis” because of that success, and because the emerging FM stations would actually play full sides. [It gave the disc jockeys more time away from the board, so they were happy too]. In this era, it wasn’t “marketing” that sold bands, it was a buzz created by live performances that led to record sales and more radio play. That’s how Canned Heat became “famous”- they put on incredible shows, the radio play gave them greater exposure and the albums sold well. Each aspect (record sales; radio play and touring) fed the other. And word of mouth was very effective too.

How effectively did the records convey what the band really sounded like?

Skip: I think the records do give you a sense of what these guys were like. Most people think of the Dead as the original jam band, but Canned Heat was doing the same thing at the same time. Live shows were often jam sessions. Most people don’t realize how constantly these guys were playing- formal shows, charity events, biker club get-togethers, and festivals, whatever. They were always playing. They wanted to play. They still do. And their fan base was devoted; from hardcore blues fans to people that just wanted to boogie.

I have early Liberty pressings of these records; they are very impressive sounding in their straightforward production- good clarity, dynamics, and tone. Can you tell us anything about the production details of any of these albums?

Skip:

I got pretty anal about trying to get the most out of the recordings; not only trying different studios, but also listening to the tapes over the car radio. The Record Plant back then had some of the best equipment, and I got some of the best sound from them; I used Doug Sax for the mastering on some of the albums; we worked really hard on making sure the albums sounded as good as possible. When the mastering was done, I would inscribe phrases like “don’t forget to boogie” into the deadwax. At one point, I had a lot of acetates that we didn’t release for one reason or another. We were pretty obsessed.

What is Canned Heat like today?

Skip: I’m still going out on the road with Canned Heat- they are still incredible. There have been a couple of different line-ups in the last few years. Fito, Larry, Harvey Mandel (on and off, due to health issues), Robert Lucas (now deceased), replaced by Dale Spalding (who played with Ray Charles); and (JP) John Paulus (who played with Mayall and had played with Canned Heat earlier). The camaraderie is amazing. At the end of a show, we all go out together and have an IPA!

These guys—the earlier members and the current line-up—all share the same attitude: none of them ever really cared about their public image; they are what they are- incredible musicians having a good time playing.

You’ve had a pretty amazing run yourself—having promoted many of the top early rock bands, including the Airplane, the Doors, Janis Joplin, Steppenwolf and The Cream, among others.[2]

You have continued to work with Canned Heat, Harvey Mandel, curated additional Canned Heat recordings, Alan Wilson recordings[3] as well as John Lee Hooker material. You also managed Kim Wilson and The Fabulous Thunderbirds.

Are you surprised by the durability, the longevity of some of these bands, not just as an “influence” but for the original material that new generations seek out?

Skip:

I am. One of the most intriguing things to me is all the young people in the audiences for Canned Heat. Some of the young fans were led to the group because their parents were fans and had the records. These younger audiences are also pretty seasoned- they’ve been to many festivals and get how good the players are in Canned Heat. I think the band is better than ever, and I’ve been with them for fifty years!

⌘

My profound thanks to Skip Taylor for his insights. One of the things I love about talking with the people who were directly involved in the music making from this era, is that they still have the passion and enthusiasm for the magic that they helped create. So, an additional, personal thanks to Skip Taylor for “keeping the faith.”

Bill Hart

Sept. 28, 2015

_______________________________

[1] Kaleidoscope, the band, featured David Lindley, one of the most gifted stringed instrument players I have had the pleasure to hear.

[2] Skip Taylor maintains a website which gives more detail on his amazing career.

[3] Skip turned me on to a relatively new release, Alan Wilson, The Blind Owl, on Severn Records, Inc. It’s a great compilation of Wilson’s work.