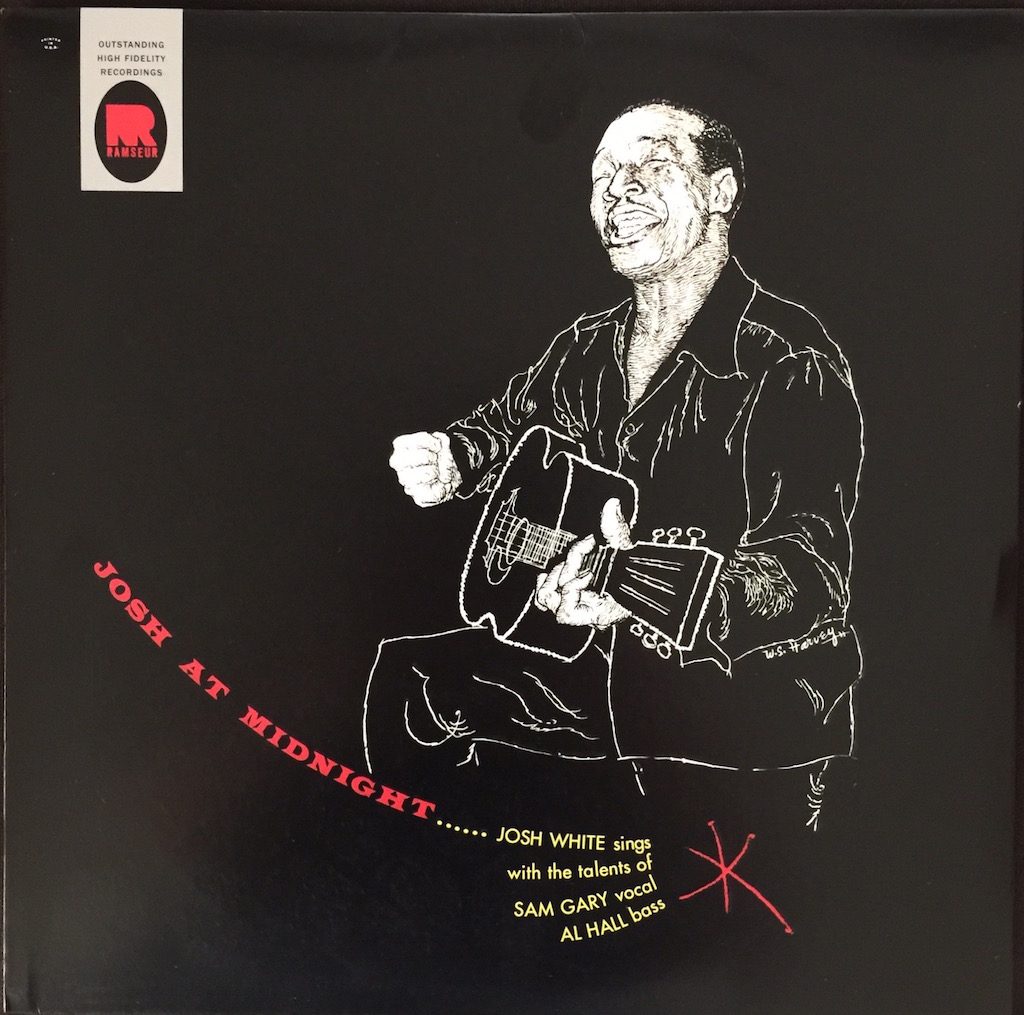

Blues is both some of the simplest and hardest music to play: I don’t care if it’s played on a Les Paul pumped through a stack of Marshalls or a beat down acoustic guitar from an old ’78—it isn’t the notes, it’s the feeling, the tone and rhythm that convey the emotion, not pyrotechnics. Josh White is somewhat of an enigma to me- he was around in the earliest days of the rural blues, learning his chops from street performers in the South where he grew up. White helped popularize a regional style of “Piedmont blues,” known for its distinctive fingerpicking and alternating bass line. It is rural blues, but of a different sort than that associated with the “Delta” – more “country” and less ominous, with flourishes of ragtime and “old time” string band sounds.

But White’s name is missing from the usual rank of favorites from the pre-War era; perhaps because they are typically associated with the darker themes of Delta blues, which later drove the popularity of electric blues (and blues-rock). He also became a well-known film, radio and theatrical star and civil rights activist in the era immediately before and after WWII, but seems far less well known today than his contemporaries, or those who were inspired by him. There are a number of explanations for this, according to Doug Yeager, Manager and Archivist of the Estate of Josh White, Sr.: after experiencing a career-threatening injury to his picking hand in 1936, White returned to the New York scene in 1939 with an altered guitar style (not as fast, but more dramatic), while his overall performance had become more refined to a polished, “uptown” style as his fame and popularity grew. Though White had considerable recorded output from the late ‘20s and early ‘30s, and a popularity exceeding that of Robert Johnson, his popular image at the height of his fame in the 1940s was not the rough, repetitive sound of the Delta blues, but a far more eclectic mix of country blues, New Orleans jazz and international folk music blended with spirituals and protest songs. White’s blacklisting during the Red Scare at the height of his fame, also contributed to his diminished popularity in later years.

White was gradually relieved of taint of the McCarthy years, even appearing during the Kennedy era in a performance broadcast on network television.[1] However, his failing health, and more mainstream folk orientation did not attract the same attention that Robert Johnson, Skip James or Muddy Waters did, when the Brits (and a few others) seized upon the “Delta” and Chicago electric blues styles. According to Doug Yeager, the blues revival in the ‘60s was searching for the more primitive styles as more “authentic” blues and electric guitarists such as Muddy Waters were more readily adapted to the harder rocking electric blues that followed. Yet, says Yeager, White still influenced a significant number of later artists, despite being overlooked as an early blues innovator and notwithstanding his being blacklisted from established media outlets and record companies in the United States.

White remained a star in Europe, where his work helped kick-start Lonnie Donegan’s interest in American music—and the development of early rock and roll in Britain. (Donegan, of course, was the pioneer of “skiffle,” the musical style that shaped the sound of the early Beatles). Even Elvis Presley acknowledged Josh White’s influence on his performing style. The “House of the Rising Sun” by the Animals—a staple of blues-rock– was inspired by Josh White’s earlier recording of the song.

This record, originally recorded in 1955 and released by Elektra in 1956, is one of his great ones, made after White was blacklisted during the McCarthy era and was already suffering a decline in his fortunes (and eventually his health). Jac Holzman, the founder of Elektra, had the courage and foresight to record White in this period, producing a mix of rural blues and spirituals that don’t fit neatly into a single “style.”

Although it drew from traditional sources, it is folk music as much as it is the blues.

The original record is long out of print, and was only reissued a few times in the years immediately following its release. Josh At Midnight helped revive Josh White’s career after being branded a political pariah.

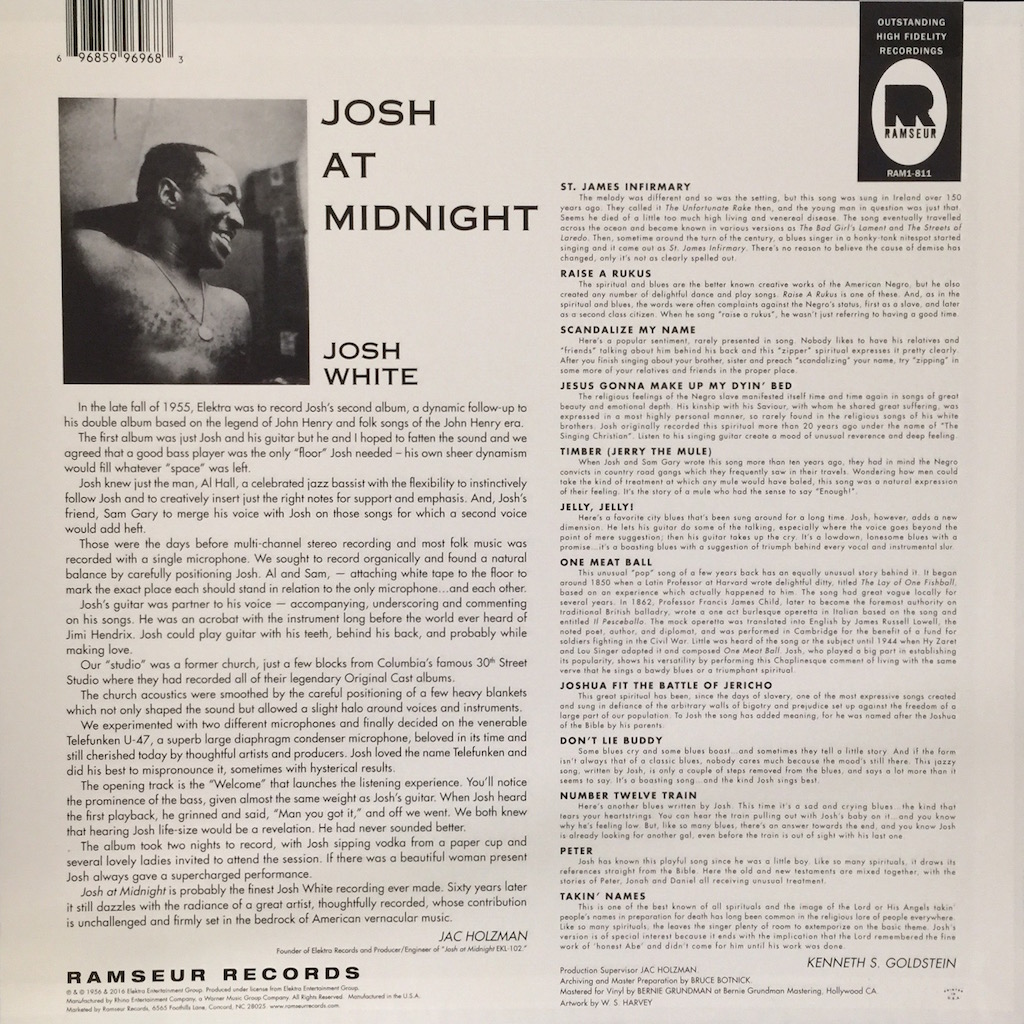

Ramseur Records, a small independent label based in the Piedmont region of North Carolina, took on this record as a labor of love: it was mastered by the redoubtable Bernie Grundman, with archival preparation credited to Bruce Botnick (who worked with The Doors and co-produced Love’s Forever Changes with Arthur Lee) and pressed at RTI.

Bernie Grundman doing his magic.

It is sourced from digital file, but don’t take that as a negative. Bruce Botnick was kind enough to explain:

We did use the original master tapes. Being that they are quite old and fragile, it was best to transfer them to 192/24 wav without any processing in order to realize the analogue lacquer master. No digital processing of any kind, leveling, EQ, dynamics, noise reduction, etc. were used in the archive. We mastered directly from the 192/24 files at Bernie Grundman mastering using their custom digital to analogue convertors and then into their totally analogue mastering system. Great care was taken to realize all of the music and to actually out perform the original vinyl release from 1956, which proudly we know that we did.

(More about that later, in a comparison with an early pressing on Elektra).[2] Dolph Ramseur, the driving force of the label bearing his name, even enlisted Jac Holzman to provide some additional liner notes for this release. Holzman knows more than a little about the recording- he not only founded the label on which the record was first released, but supervised the production of Josh at Midnight as EKL -102.

The record, not surprisingly, is in mono, and as Holzman tells us in the liner notes, in “the days before multi-channel stereo recording… most folk music was recorded with a single microphone.” The mike used here was a Telefunken U-47, a legendary piece of gear that has been used on countless famous recordings.

The recording itself is simple, made in a de-sanctified church with modest acoustic treatment. Al Hall, a well-recognized jazz player, accompanied on bass and additional vocals were provided by bass-baritone Sam Gary to lend “heft” to Josh’s tenor singing voice. Josh played guitar. As Holzman implies in the liner notes, that’s a little like saying Jimi Hendrix played the guitar. There were Josh White branded guitars and even a guitar instruction method bearing his name in the ‘50s.[3] Guitarists like Bert Jansch (himself a hugely influential player) and a number of other famous artists—among them John Fahey, Bill Wyman, George Harrison, Ry Cooder and John Fogarty– revered him.

With this lead-up, what does the record sound like?

It’s a marvelous combination of vocals in the caliber of the best—think: Sam Cooke—combined with virtuoso guitar work that instantly changes from old time country to blues leads to jazz. The bass playing is superb, bowed, plucked, sometimes in counterpoint but always in time. Gary’s voice does add weight and balance where needed, but Josh is so good, it is easy to overlook how musical the other two guys are- at times, the vocal parts have an operatic quality, at others they are almost scat singing to a frenetic pace. One oddity- there are no drums on this album and what’s odd is you don’t notice their absence—in fact, they would be superfluous. These guys carry it all.

Let’s talk about the music and sonics at the same time.

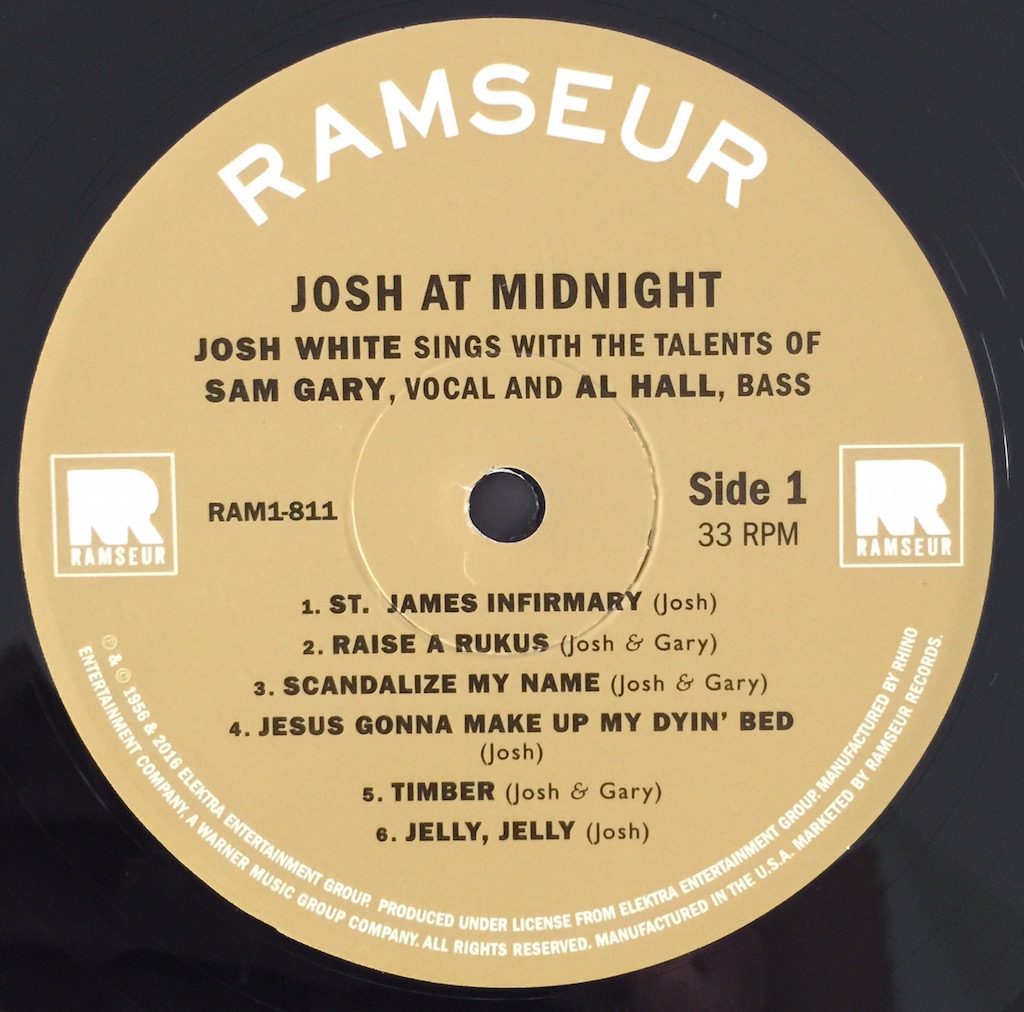

Side One

St. James Infirmary– the old standard, but at a faster, almost upbeat pace. The bass is distinct and tight in counterpoint to the vocal; Josh’s guitar lines are tangy and his voice is honey. The bowing of the bass and jazz guitar licks at the end are a nice finish.

Raise A Ruckus– the countrified side- with an old time spiritual vibe. These guys are spitting out the lyrics to keep pace with the beat.

Scandalize My Name– another spiritual, the interplay between vocals is central here. Josh’s guitar work is subtle.

Jesus Gonna Make Up My Dyin’ Bed– a slow-paced bluesy piece, Josh’s voice carries this, but the guitar fills sound like slide parts played in finger-picking style; the bass is both plucked and bowed. Another jazz guitar lick closes the piece. One of my favorites on this album.

Timber (Jerry The Mule) – a work song about a mule, mixing the “negro spiritual” with almost operatic vocals. Jazzy guitar fills, with a pace that is relentless. It’s on this song I realize there are no drums on this record, and they aren’t needed.

Jelly, Jelly! – an “uptown” blues, suited for a fancy club, but gritty nonetheless. Josh’s voice is gorgeous here, which is a little incongruous for this lowdown kind of tune, but it works. Josh’s guitar work here is again perfectly underplayed- he keeps the rhythm going and adds zippy blues fills.

I compared this long overdue vinyl reissue/re-master (thank-you, Ramseur!) with an old Elektra copy which, based on the label design, appears to be from 1961.

What I heard was counter to my usual expectations (and experience) with digitally sourced re-masters compared to their analog ancestors- rather than sounding brighter, the Ramseur was darker and more polite. This was evident on the “Timber” and “Jelly” tracks. The guitar on the old Elektra sounded hotter and everything was a little more “in your face.”

I don’t run a dedicated mono cartridge and arm- figuring that the Ramseur, mastered on a modern lathe, wouldn’t suffer from that, but who knows? I did adjust the VTA a bit, even though my current cartridges (Airtight for the last number of years) seem far less sensitive to minor differences in record thickness or cutting angle than the Lyras I used in the past. However, the differences between the two records were not entirely consistent. The bass on “Raise a Ruckus” was great- better tone and depth compared to the Elektra and on “St. James Infirmary,” the Ramseur pressing sounded more relaxed; the old Elektra sounded almost frenetic by comparison.

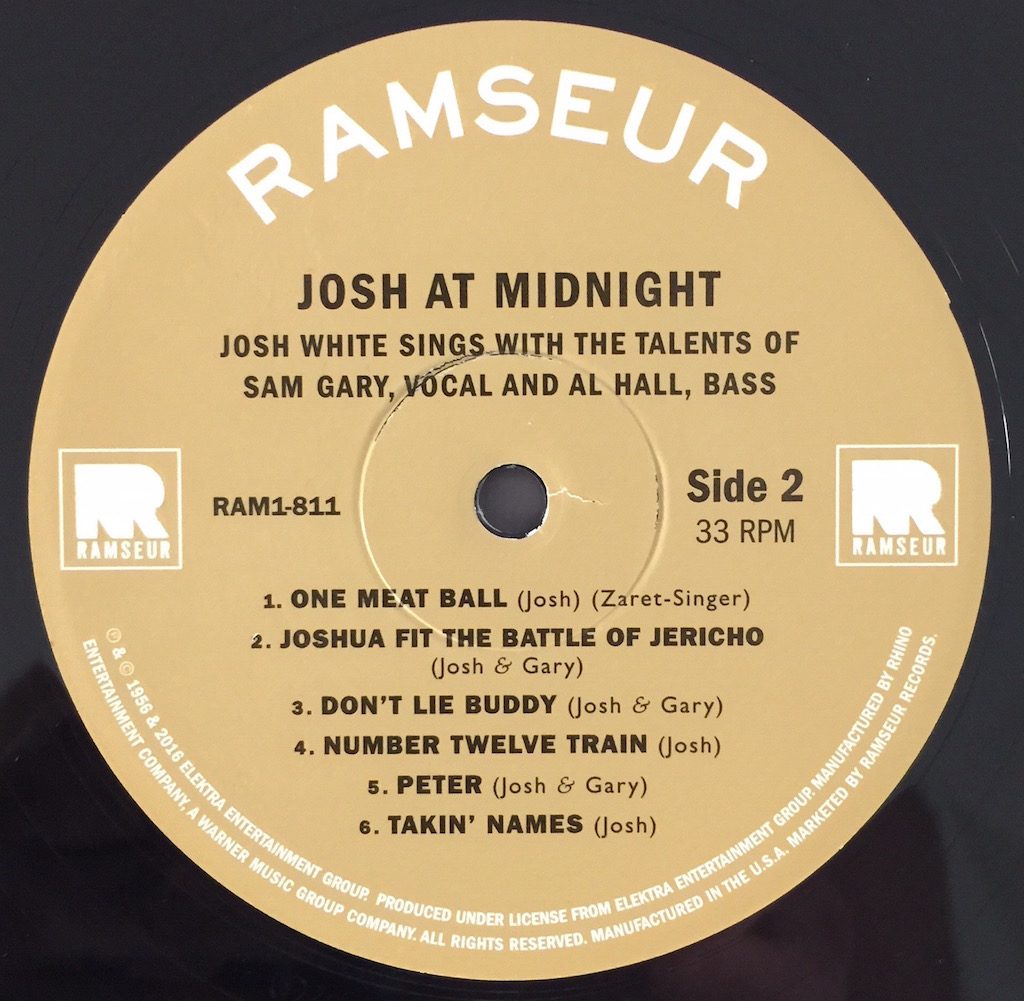

Side Two

One Meat Ball- titles can be deceiving- an old novelty song that is a gorgeous piece of singing by Josh. It carries a funereal character more than St. James Infirmary- another classic that makes this record worth buying.

Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho- this spiritual starts with an almost Spanish style guitar intro, then dueling vocals at a breakneck pace tell the story from the Bible; these guys can turn from operatic to scat in the blink of an eye.

Don’t Lie Buddy- Josh’s voice is beautifully soulful here, and accompanied by a rollicking chorus. You can hear the harmonics of the guitar well on the Ramseur.

Number Twelve Train- a slower, more classic blues, Josh’s voice is so delicious you almost miss the meticulous bass and guitar work, but when Josh breaks for a little guitar solo, you get to enjoy the instrumental work—spare as it is– standing alone.

Peter- another spiritual that seems to speak to Jonah (and the whale) more than Peter, but then Daniel gets added into the story, and we are bouncing between them when Peter joins and then it makes sense.

Takin’ Names- haunting, an old time spiritual sung like “House of the Rising Sun,” but blues-bent. This song is the killer for me and worth the price of admission. I like minor keys, so Josh’s voice – rich gold- sails above the darkness. I think I prefer the tonality of the Ramseur pressing to the old Elektra on this track.

It would be too facile to say one pressing is better than the other; I’m hearing more sometimes on the Elektra but it is also brighter sounding. At this point we are dealing with a 60-year-old recording, so what you get on the Ramseur is a nicely pressed, well-mastered, quiet representation of a set of historical performances that will engage you in a number of different ways. I’m not even sure I care that much about the “audiophile” attributes given how good the singing and playing are here, but to the extent it matters, I think most readers will be delighted with the Ramseur, particularly if you have the ability to tweak your arm height a bit. The old pressings aren’t exactly scarce, though condition is, as always, going to be an issue. White’s legacy – that of an extremely talented artist who was a foundational figure in blues, folk and protest songs with a large body of eclectic work over the decades— is sorely unrecognized by modern audiences, yet he still endures. Through this new issue on vinyl, a new generation of listeners can appreciate why this man is so important, not just for the sake of history, but for pure musical enjoyment.

♦

I had a chance to speak with Dolph Ramseur about the project:

Why this record?

I grew up in the Piedmont area of North Carolina. In 1978, I saw Steve Goodman on the Austin City Limits television show- just him and the guitar. My dad was watching with me and he was laughing and crying at the same time. I didn’t fully understand why he was so affected by that performance. Around this time, a local radio show out of Charlotte was broadcasting programs dedicated to the Piedmont blues. Virtually everything they played was one man or woman and a guitar. I don’t why, but it just fascinated me that these people were fingerpicking. (Reverend Gary Davis sounded like five people playing at the same time). It made me think about that Steve Goodman show I watched with my father. One day the Charlotte station played some Josh White tracks- I used to go to the local library or record store and get the records I heard on the radio. So, I started buying Josh White records. There was something about Josh that jumped right off the record to me- you could detect traces of Josh’s influence in Nat King Cole’s work. I started researching Josh White –I was probably 13 or 14 years old at this point – he was a great guitar player, but he was the voice of Piedmont blues, and to me, his work remains unmatched. He was something special.

When you enlisted Jac Holzman to write additional liner notes from a contemporary perspective, you must have had one of those “I’m not worthy” moments, no?

Jac is a legend and one of the most brilliant people I know in this business. I think Jac was so pleased that there was renewed interest in the record, because the record was important to him when he recorded it back in the day.

Did you attend any of the sessions where Botnick or Grundman did their magic?

I was there with Jac, Bernie and Bruce (Botnick) when the vinyl was cut. It was not only a great experience because of the people involved, but because of the importance of the recording itself. Seeing it being cut on a lathe at the hands of a top mastering engineer was one of those special moments in life for me—I know Bernie has done a lot to improve the mastering chain since the “old days,” but the reality is, we were (re-)cutting a very important record using essentially the same type of technology that was around when the record was first released 60 years ago!

You represent talent, in addition to running a label. How many different recordings have you released?

So far, 41 releases. More to come….

Are you planning to do more remasters?

Yes, I’d love to do more- this all comes from the music I love.

Dolph Ramseur listening at home.

The Ramseur Records website is: http://ramseurrecords.com/

You can buy the Ramseur re-master on vinyl directly from Ramseur online or from the “usual” online sources in the States.

Bill Hart

August 10, 2016

Photo credits: Image of Josh White, courtesy of the Estate of Josh White, Sr.

Photo of Bernie Grundman at work, courtesy of Dolph Ramseur with permission of Bernie Grundman.

Photo of Dolph Ramseur listening at home, courtesy of Dustin Peck.

Many Thanks to Dolph Ramseur, Doug Yeager and Bruce Botnick for providing some of the history of Josh White’s career and the backstory of this recording.

_____________________________________________

[1] White had performed at the White House for FDR in 1941. For a more in-depth examination of Josh White’s life and music, see Wald, Elijah, Society Blues, http://www.elijahwald.com/josh.html.

[2] Ramseur also told me that the resolution of the transfer supervised by Botnick benefitted from more modern tape heads in the process.

[3] Yeager advised that Josh was the first African-American guitarist to have a signature guitar mass-produced, first by Zenith in Europe in the ‘50s and then by Ovation in the ’60s. The latter was Ovation’s first commercial guitar.