Inside A&R Studios in its Heyday-Glenn Berger Recounts the Golden Era Working with Phil Ramone

This is the rare “insider” book on the rock music business in its heyday: rare because unlike the name-dropping, image-burnishing autobiographies of many fabled artists and engineers, often told from the vantage point of age and (sometimes faded) celebrity, we are in the studio—Phil Ramone’s to be exact—witnessing the performances and engineering craft of the best in the business through the eyes (and ears) of a young intern/apprentice/assistant engineer. The author, Glenn Berger, managed to get in the door of A&R studios as a “schlepper” and then to “assisting” assistant engineers before he worked his way up to a fully-fledged recording engineer in his own right. Along the way, he attracted the attention of Phil Ramone, the incredibly talented (and demanding) studio boss who had already achieved legendary status in the industry. Ramone’s studio, shabby and tired, yielded some of the greatest popular music recordings ever committed to tape.

Berger’s perspective – that of a young, earnest kid from Brooklyn, nervous, attempting to hide his awe and quickly learning the “moves”—from the position of the faders on the console to the politics of handling star performers—is refreshingly honest, and told without guile. For Berger, it was a mixture of wonder bordering on terror, as he bears witness to the creative process of some of the greats –Dylan, Paul Simon, James Brown and Frank Sinatra, while performing yeoman’s tasks in the control room assisting other engineers, including Phil Ramone himself.

We get a little of the “dirt” but that isn’t Berger’s aim. Instead, Berger is attempting to chart the “magic” of the creative and engineering process; why some of these recordings were so musically and sonically special when released and why they remain so, forty odd years later.

One reason Berger can so clearly voice what happened is that he did not remain in the “biz”- he isn’t putting a gloss on the narrative because he is not still dependent on industry relationships to make a living. In fact, before reading this book, I had no idea who Glenn Berger was—he is now a “shrink” in Manhattan; the passage of years and accumulated experience have not made Berger more jaded or nostalgic, but afford him with real insight into the crazy organized chaos he participated in during the mid-‘70s.

And those years were wild. New York was dirty, dangerous and bankrupt. The music business was booming.

Drugs and sex—which always seem to feed these tales—were less lurid and more about self-medication: to keep running through brutal overnight marathons, to release tension or simply to escape the relentlessness of the work. But the constant here is not the excesses: instead, it is the disciplined, far more finely honed commitment by the artists and engineers to craft something that captures the emotion and moments of inspired genius that are so ephemeral and so easily lost.

The engineer’s job is to memorialize the artistic process on tape (then the native medium of the studio), without interfering with the artist’s momentary, often elusive inspirations. At the same time, the engineer is hardly passive- the process involves some mindreading (really anticipation of where the artist is heading) and some “on the fly” re-jiggering of temperamental equipment to make it all work. A moment lost from the tapes is lost forever. And the basic tracks are just the beginning. Then comes the work of comparing takes, melding pieces together, mixing, overdubbing and adding assorted studio wizardry. As Berger so well recognizes, “What came as a revelation was when I came to understand just how much artifice was required to make something sound ‘real’.”

We read about the mysterial Bob Dylan, creating Blood on the Tracks in a raw outpouring of emotion, dismissing session players with the wave of a hand when they failed to follow his unrehearsed changes in direction. The sessions captured at A&R were replaced in part on the commercial release—a great record to be sure, but different than the one Ramone (and Berger) recorded.[1]

Sessions with Paul Simon make you realize how much of a perfectionist the man is—Berger’s account isn’t very flattering to Mr. Simon, but Simon’s single-mindedness almost jumps off the page. Even the “great Ramone”—who could be a manic terror– seemed cowed by Paul Simon.

Ramone is an essential part of the story—a “star” in his own right, but also fighting his own demons, gruff, mercurial and gifted. Berger’s description of Ramone’s genius in a moment of crisis is inspiring: with Allen head screwdriver in hand, Ramone is realigning the azimuth of a tape head of a recording deck on the fly, moment by moment, during playback of a an entire album’s worth of material; the original master tape, representing months of work, had been fouled by a series of technical mishaps. Hard against the deadline to rush the finished, mixed-down tape to the West Coast for mastering and production, Ramone engaged in a bit of improvised technical alchemy to avoid a major professional disaster.

Everybody was working beyond their limits- physical exhaustion, lack of sleep, the demands of a studio running 24 hours a day, finicky equipment— and the toll it took on these guys behind the glass becomes obvious. There was glory in it, but for most engineers –who, unlike producers, did not get a “piece of the action”–the price was high and the rewards were more psychic than financial. (The reward was also more work, because a hit attracted more clients). By this time, Ramone had long been recording top tier artists and transforming himself into a producer as well as engineer.

One of the more touching chapters recounts the sessions with Phoebe Snow (née Laub) an awkward, ungainly young woman with a strong New Jersey accent who could deliver poetry with her sweeping range and unconventional vocal style. The session musicians for her debut were first tier, as was the recording. (That record has enjoyed a lot of time on my turntable since it was released and still gets played here). Berger captures his own muse in his homage to Snow:

What was it in Phoebe that engendered such fierce loyalty among her adoring fans? Of course she was a natural singer. She had a voice like no other, and when she opened her mouth, a sound came out that was joy burnished with pain. She was all contradiction: a jazzy, folky, bluesy, rockin’, funky Jewish chick from Jersey. But it was more than that. Phoebe was an oddball.

I understand this misfit thing. I’ve always been drawn to these types. I guess I’m one myself….

I think those among us who are different have a little less of a psychic immune system than everyone else. They are a little closer to the source. They don’t quite make it in this world, and they feel the pain a little more acutely than the rest. But they bring us a gift we all need to know and feel….

Phoebe touched this sensitive, longing, part of us. There are plenty of misfits in the world. Maybe there is a misfit residing in each of our secret hearts. I can picture all the lonely freaks out there, sitting alone in their bedrooms in 1974, listening to “Poetry Man,” and feeling some solace because they knew that she knew…

That’s what the artist does— sees for us —suffers for us, because we’d rather not go there ourselves. So, we live through them emotionally, yet vicariously….

Never Say No, pp. 107-8.

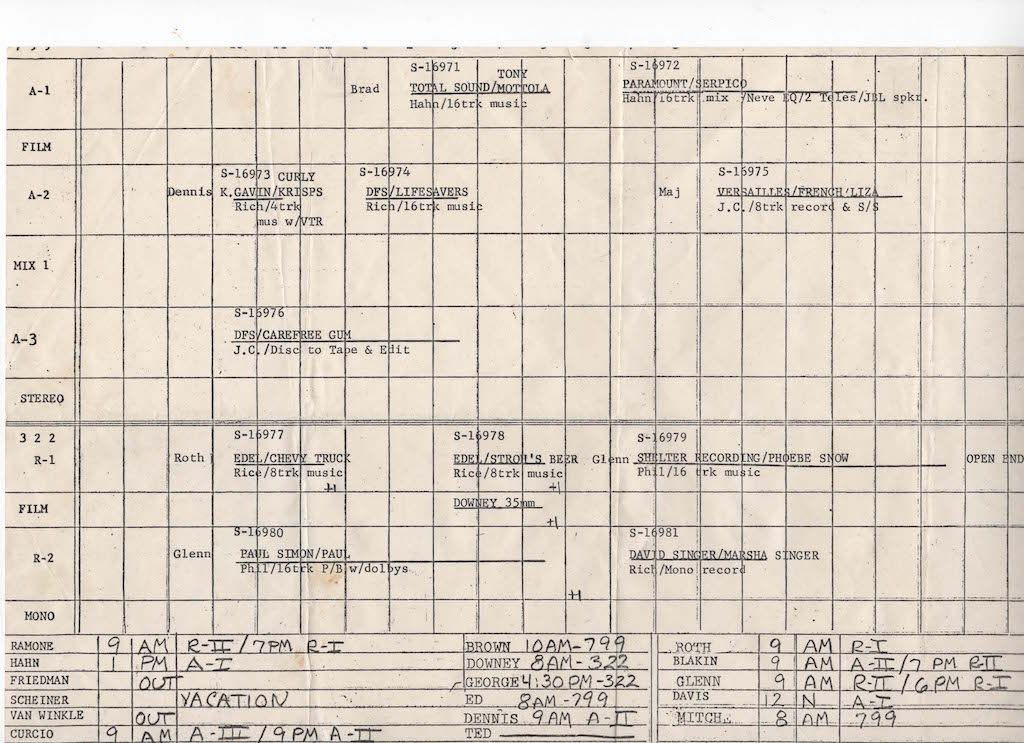

There are many, many familiar, famous names here: the sophisticated wit of the team of Becker/Fagan a/k/a Steely Dan; the funkiness of James Brown; the talent and taste of Judy Collins (who, according to Berger, helped discover Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen); take sheets with names like Paul McCartney and Burt Bacharach; mix and overdub sessions with Mick Jagger. And that one word name- Sinatra- that makes even the biggest stars go quiet.[2]

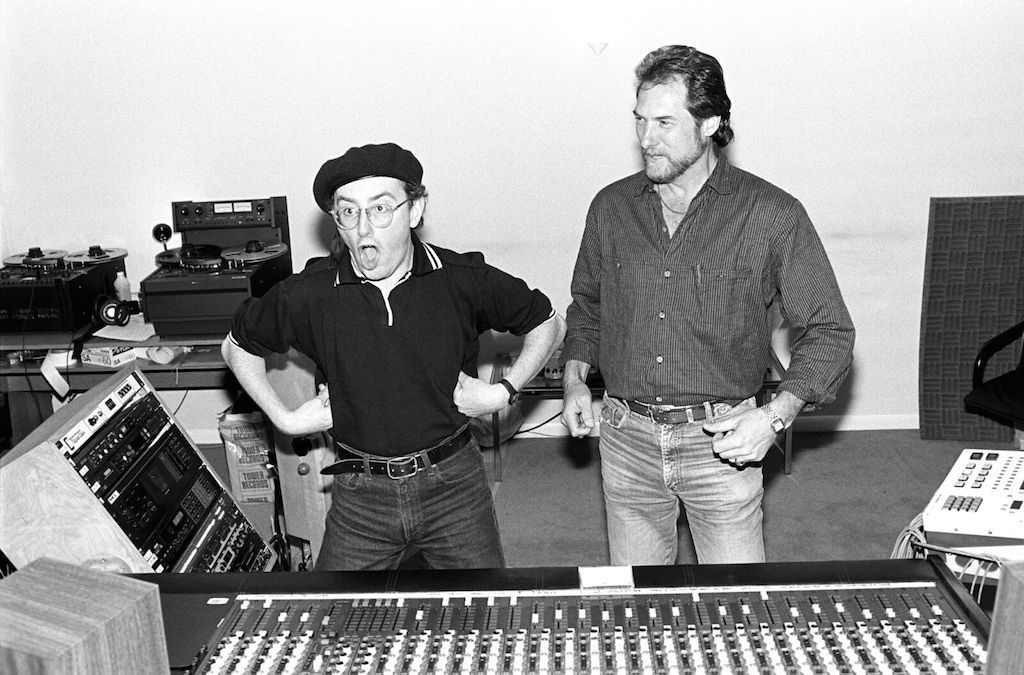

Berger lived some serious music history and helped make part of it. And despite his descriptions of a mercurial Ramone, raging one moment, placid as Buddha the next, Berger rightly recognizes Ramone’s genius, including Ramone’s ability to attract a host of young protégés who went on to achieve legendary status in their own right as engineers and producers. Although Berger and Ramone eventually broke ranks and quit working together as a team, both remained at A & R as Berger “graduated” to a senior level engineer at the age of 21 (and the youngest senior mixer in A & R’s history). He went on to work on sessions with Sinatra and Bob Fosse, eventually leaving A&R to work as an independent engineer, including a torturous stint on the optical soundtrack to the film of Fosse’s All that Jazz, an endeavor which went beyond the limits of the technology as well as Berger’s sanity. He also recorded Steve Cropper, one of the driving forces of the Stax house band, and Wilson Pickett.

But, the name-dropping and shenanigans aren’t the point. Though the book is a good read simply to understand some basic engineering tricks and techniques from the glory days of analog, (when an edit or overdub was not a mouse-click, but a more grueling bit of mechanical artistry involving tape splices and bouncing tracks among machines), that, too, is only part of the story.

Despite the horrendous pressure, the sleep deprivation and make or break tension that burdened even the “great Ramone,” Berger was still entranced- after a brief respite in Europe, he wants to understand music “from the inside,’ he tells one New York music teacher; “I’m looking for the magic.” Berger (schlepping again, since one never completely ascends a summit, but meets the next one) heads to the Boston Conservatory of Music, only to learn that one of the great teachers there makes a living playing nursing homes to deaf people.

Although he no longer works in the music business, Dr. Glenn Berger, Ph.D. is still searching for the magic. But, I think he’s long known the answer: it’s in each of us. The trick is how to tap into it, and let it flow. That takes more than raw talent, it takes courage.

Highly recommended.

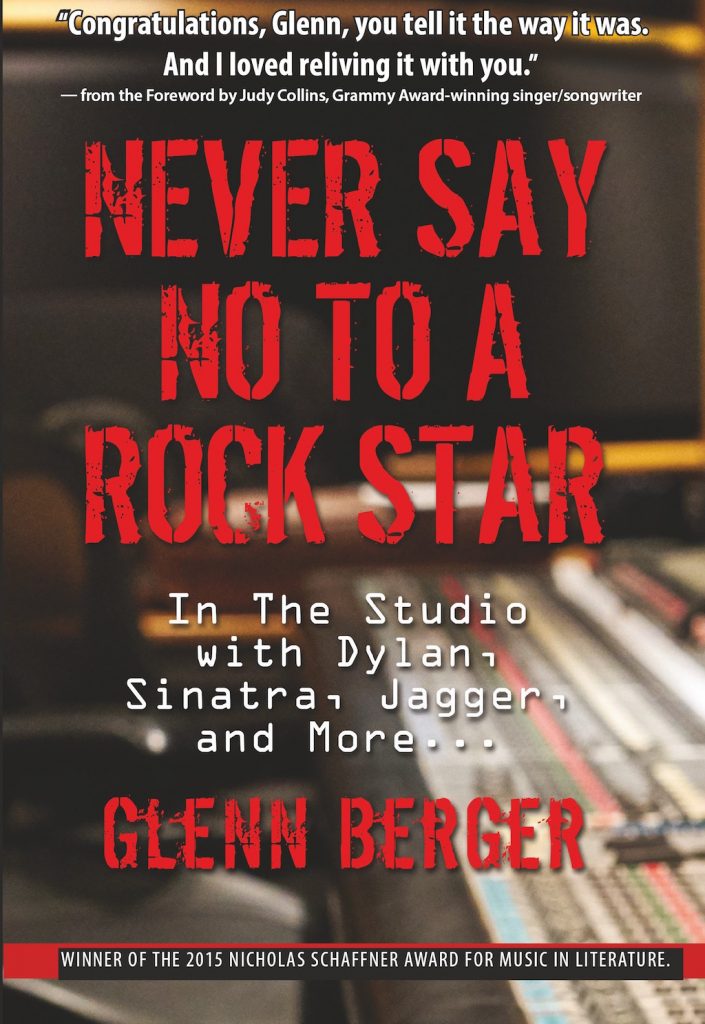

Berger, Glenn, Never Say No To A Rock Star

In The Studio with Dylan, Sinatra, Jagger, and More

schaffner press, 2016.

A fascinating interview with Glenn Berger about the book can be found here.

Glenn’s blog has space devoted to his book and you can buy a copy through the links he provides to major online retailers.

Bill Hart

August, 2016

__________________________________________________________

[1] The individual tracks from these New York sessions have been released here and there on other records, but the original record—only embodied in some test pressings and possibly, some promotional copies—has long been fodder for the bootleg community.See http://www.searchingforagem.com/1970s/International018.htm

[2] For those unfamiliar with Sinatra’s relationship with Mitch Miller, the former head of A&R at Columbia, the story is told here.

Photo credits:

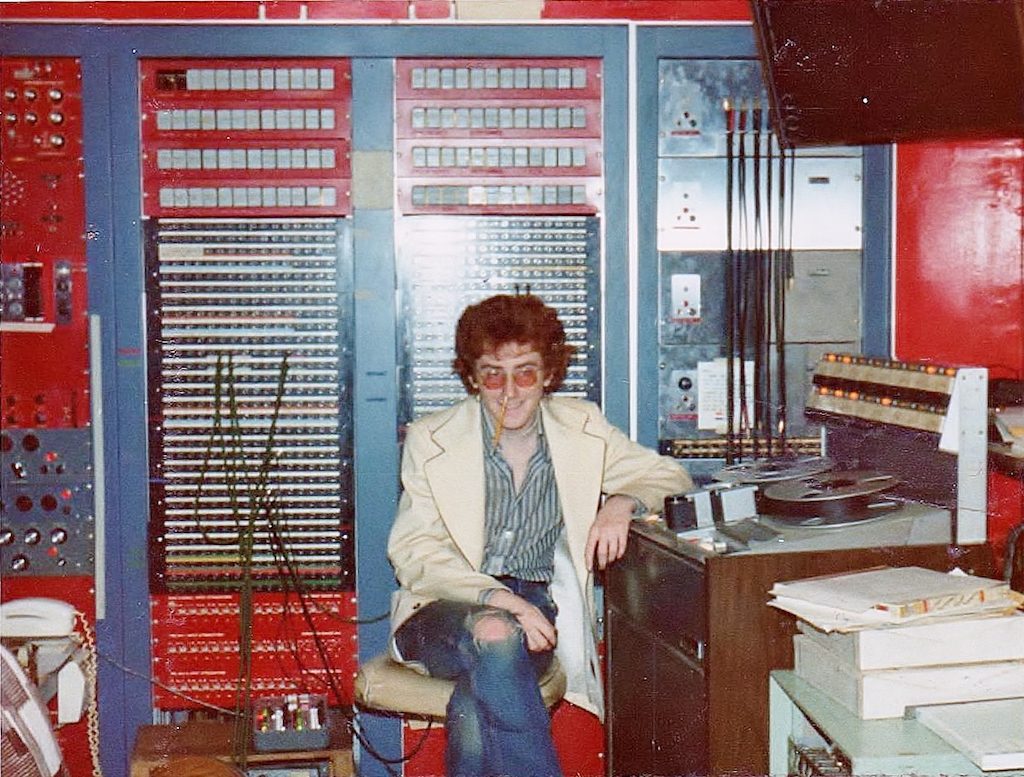

Glenn Berger (with pencil in nose) by Brad Davis at A&R Studios, 1974.

Neumann console photo by Bernie Drayton.

A&R Schedule by Larry Franke.

Glenn Berger and Steve Cropper at Krypton Studios, 1988, by Ebet Roberts.

All photos by permission of Glenn Berger.