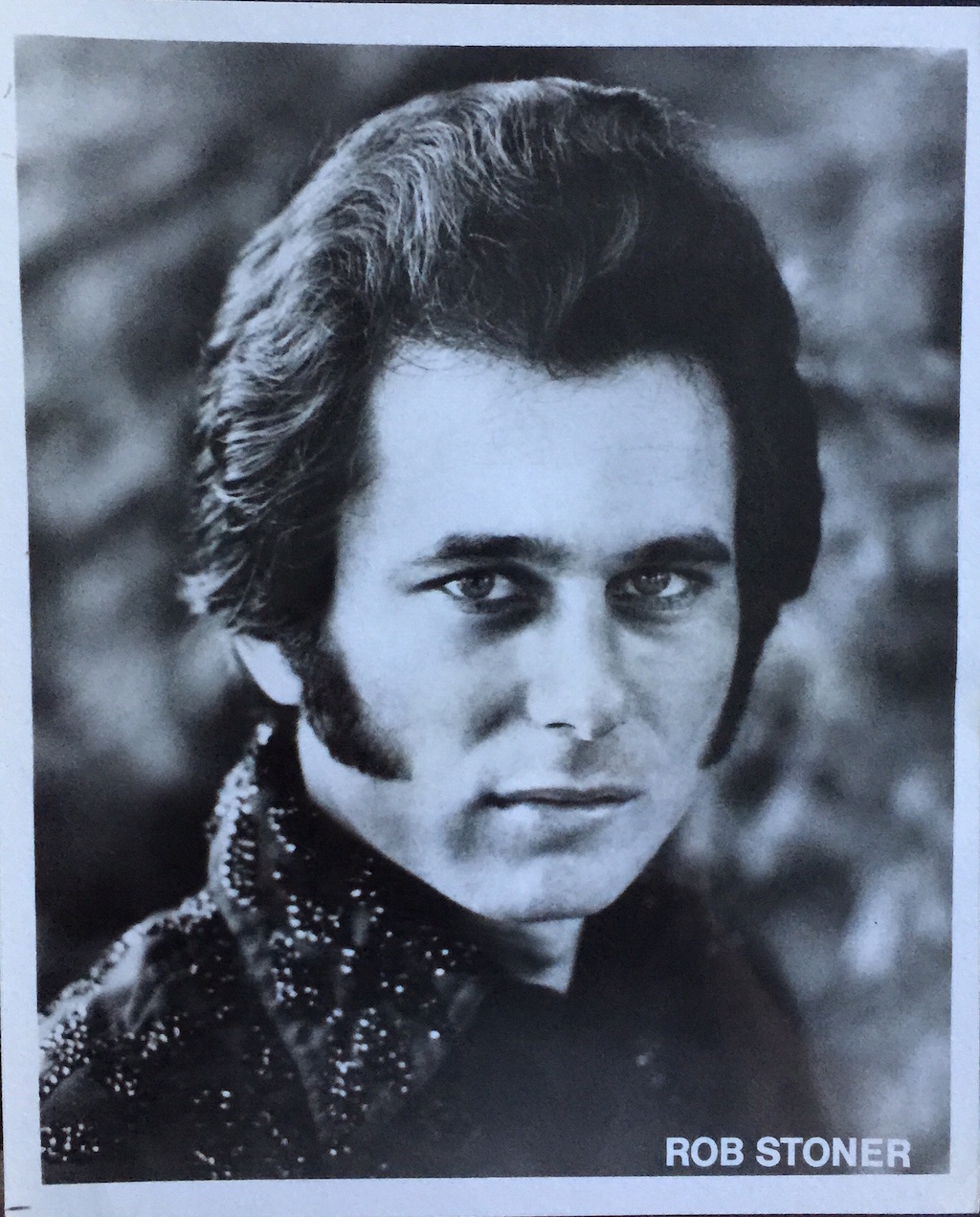

Rob Stoner: A Life of Music

Few musicians can claim to have opened for the original Jeff Beck Group in ‘68 (with Rod Stewart, Nicky Hopkins and Ronnie Wood), backed Don McLean on his perennial hit and album, American Pie and then helped Bob Dylan reinvent himself (again) in a series of albums and roadshows in the mid-‘70s—in what is now recognized as a peak of creativity for that mercurial troubadour. Rob Stoner did all that by the time he was 27 years old. Stoner didn’t stop there: he played with guitarists as legendary as Chuck Berry and Link Wray, as great as Mick Ronson and as talented as Chris Spedding (I’m leaving out Clapton for now, he comes later) and worked with vocalists as diverse as Roy Orbison and Joan Baez.

Anton Fig, Link Wray, Robert Gordon, and Rob Stoner

Rob Stoner’s performing and recording credits– as a bassist, guitarist, keyboard player and vocalist—read like a Who’s Who of 20th century popular music.

The measure of Stoner’s talent comes not from the fame he has enjoyed throughout a long, storied career, but from his enduring recognition as a “go-to” musician by almost everybody else in the business. They all know him, seem to have played with him and respect him. Spend time with Rob and you’ll be involved a discussion about Charlie Christian’s early use of the amplified guitar as a solo instrument in the big band era, or the evolution of rock and roll in England before the “skiffle” craze that led to The Beatles: Stoner’s knowledge of music is vast, deep and encyclopedic.

I though readers might enjoy being part of that discussion with Rob, who was kind enough to give us some time:

You started playing professionally at a young age.

RS:I was 14 when I started making money as a gigging musician while in junior high school; by the time I got to college and moved to Manhattan, I was working regularly. One of our regular gigs was as an opening act for bands that were touring for the first time in the States. We opened for Jeff Beck, Sly and the Family Stone, Deep Purple and many others. My college band had steady work at Steve Paul’s Scene, Cafe Wha’ and the Electric Circus. We were signed by Lieber and Stoller for publishing and production, so we were pretty plugged in at a young age. Our group used to rehearse in one of the rooms in Lieber and Stoller’s suite in the Brill Building. By 1970, I was getting noticed for my playing and singing which led to some session work.

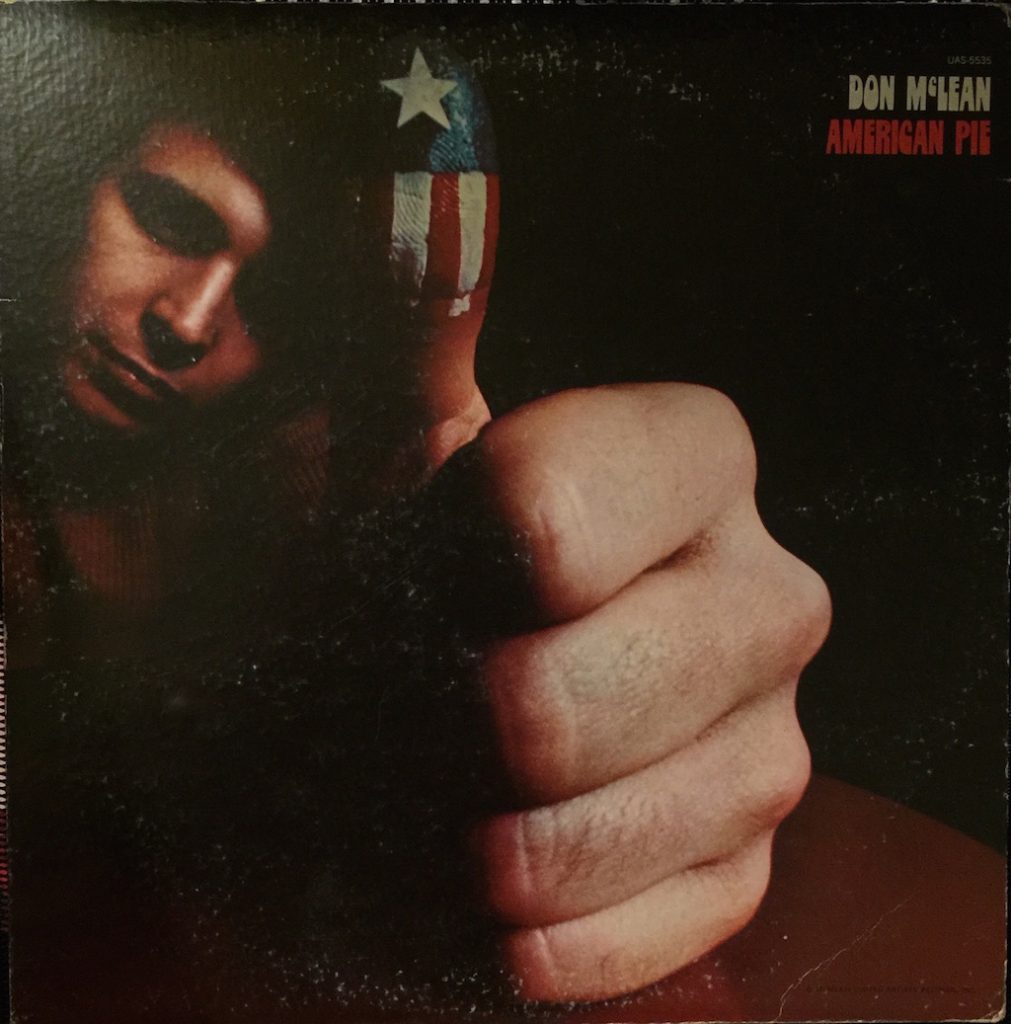

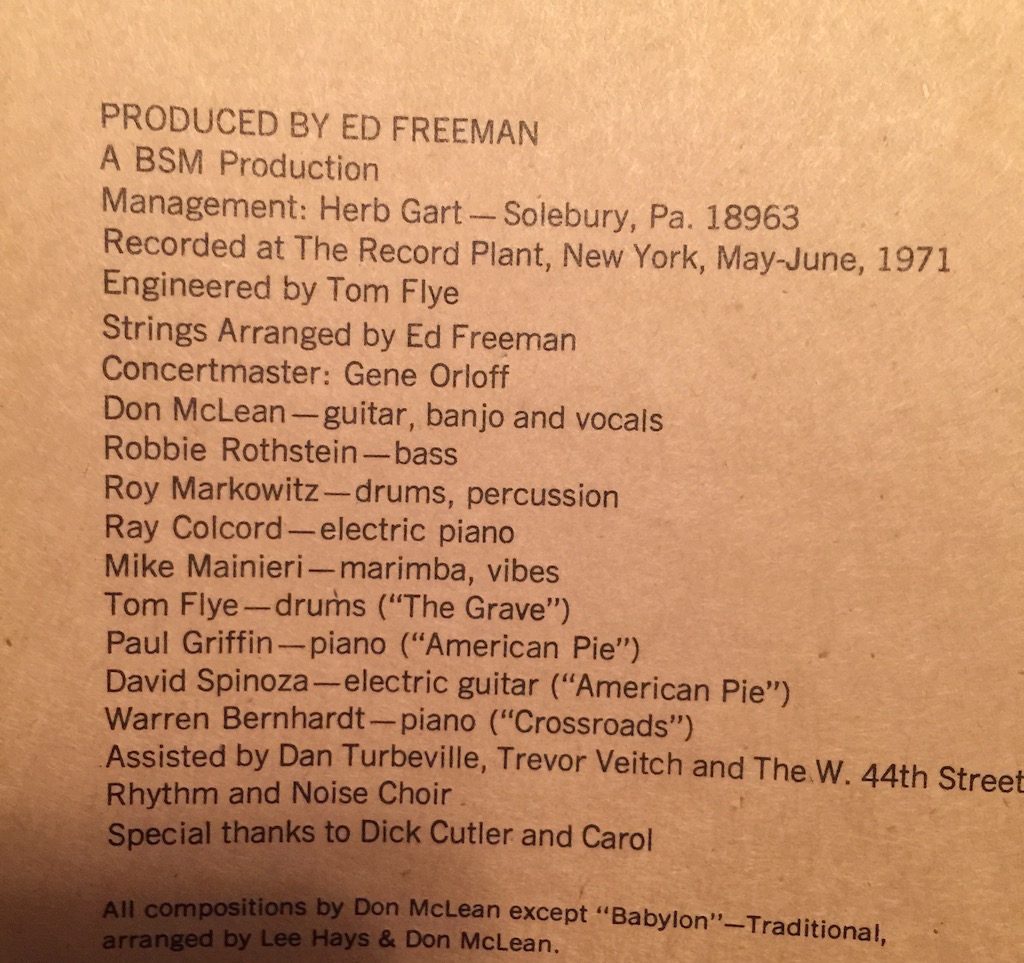

How did you wind up working on American Pie?

RS:Producer Ed Freeman hired me to play and sing backup on Don’s first album, Tapestry, and I was called back for American Pie. At the time, I had been working in the folk scene in New York- Pete Seeger, Ramblin’Jack Elliott, and Tim Hardin were among the artists I played with at that time. The success of American Pie made McLean a huge success that transcended the folk scene and led to more work for me.

Midnight Special, Don McLean and Rob

You are credited as “Robbie Rothstein” on American Pie. How did you become Rob Stoner?

RS:We’re getting a little ahead of ourselves, but when I was signed to Epic as a solo artist, they conceived of me as a “country” act. Ethnic names weren’t really part of the Nashville scene then. “Stoner” was an anagram of “Redstone” which is the translation (from German) of Rothstein. My cousins and I had a group called the Redstones in the early 60’s. What’s funny is that the word “stoner” didn’t carry the same meaning it does today. The term wasn’t in the lexicon yet.

It was just a cool sounding name I chose. Coincidentally, my birthday is April 20. And that now happens to be “National Weed Day.” Sometimes, truth is stranger….

So, what happened before you headed to Nashville?

RS:After I finished the McLean gig, I began working with John Herald, a serious bluegrass player who had crossed over into the college market. His band consisted of top tier players such as Frank Wakefield and Alan Stowell. Each of us would get featured during a show. I first met Bob Dylan at one of these shows in L.A in 1972. Dylan was an admirer of Herald’s work with the Greenbriar Boys. Some of the earliest instances of public recognition for Dylan resulted from a laudatory write up he received from Robert Shelton of the NYTimes when Bob was the Greenbriar Boys’ opening act. The Shelton piece previewed a first glimpse of what Bob Dylan was to become in the public’s eye: https://www.nytimes.com/books/97/05/04/reviews/dylan-gerde.html

Herald was a little known but transformative figure—he channeled the Stanley Brothers and Woody Guthrie in many ways—and in turn, influenced Dylan.

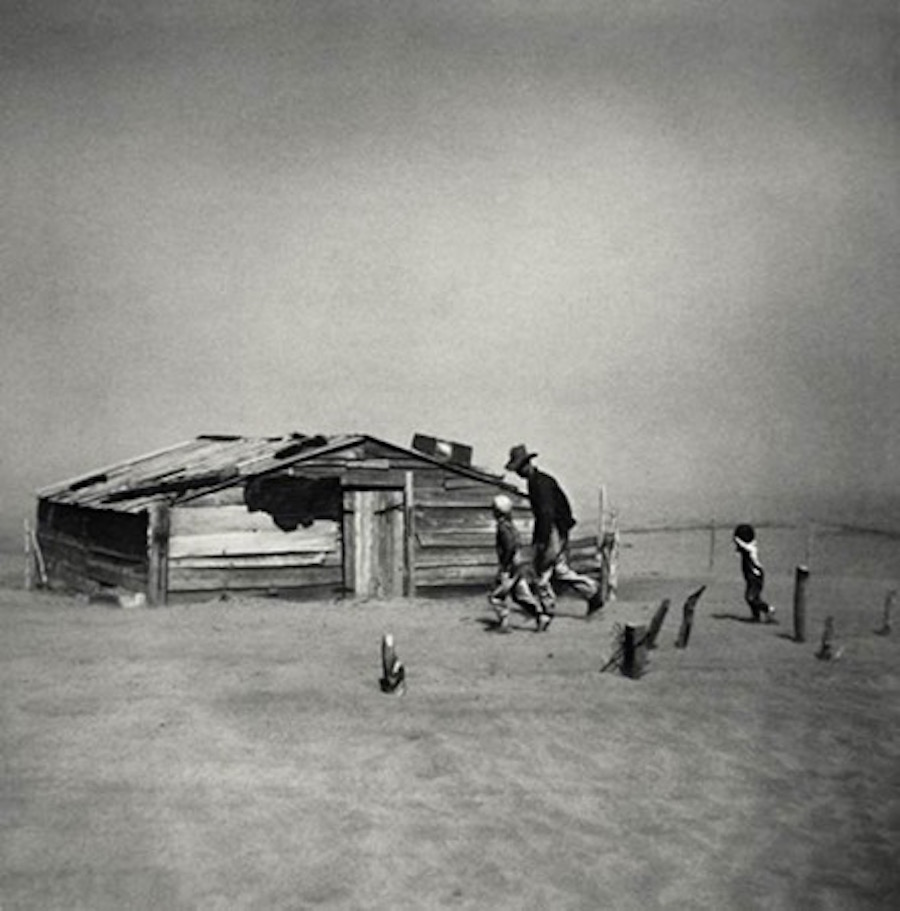

Editor’s Note: There is a “small world” aspect to this too. Woody Guthrie’s first album, Dust Bowl Ballads, recorded in 1940, and later released on Folkways Recordings, also featured an iconic image of the dust bowl—a photo taken by Rob’s father, Arthur Rothstein, whose images taken during the Great Depression for the FSA are considered an important part of our cultural legacy.[1]

Dust Storm, Cimarron County Okla. 1936

RS:I had put together a band, “Rockin’ Rob and the Rebels” which included Howie Wyeth, my brother, Dan Rothstein, Ken Pine from The Fugs and a steel guitar player from Staten Island named Hank DeVito, who later achieved great success as the songwriter of “Queen of Hearts” and other country hits. We had regular gigs at Max’s Kansas City, Folk City on West 3rd Street and other venues up and down the East coast.

RS:I lived on Charles Street, so I met many movers and shakers on the Village scene during this period. Tom Werman, who I knew from college (and later went on to produce Motley Crue and other heavy metal acts) and Gregg Geller (responsible for many Elvis Presley re-masters after Elvis’ death)– were doing A&R work for CBS/Epic at this time. Those are the guys who brought me into the Epic family in Nashville.

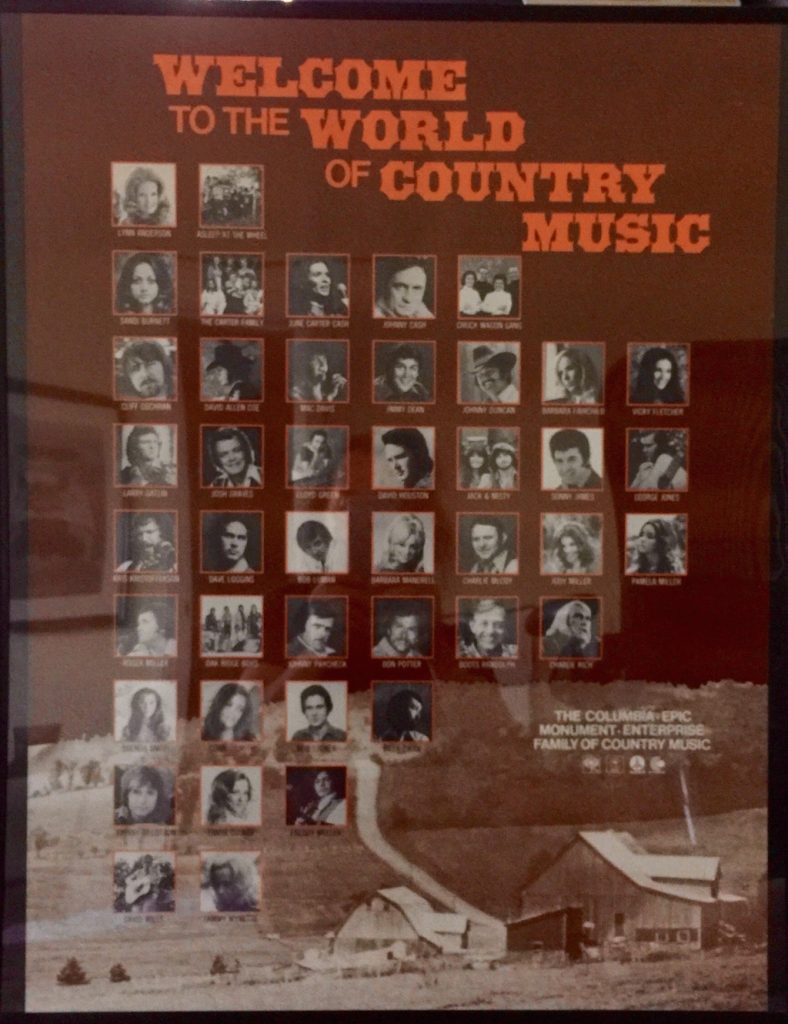

The Epic “Country” Roster in the early ’70s

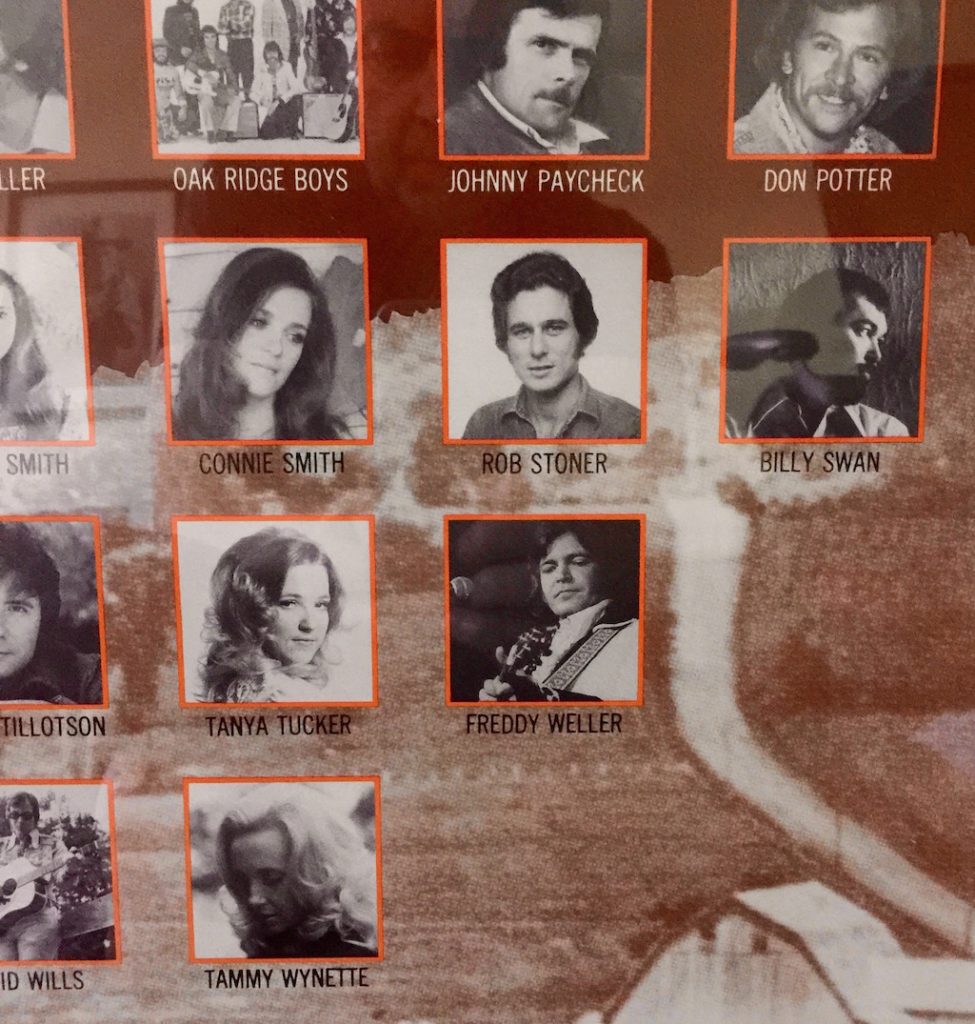

Close-up, with some of the “usual suspects.”

I guess Hank DeVito’s steel guitar playing made them categorize you as “country”?

RS:Yeah, but country music and rockabilly were a novelty in NYC in 1973, so it wasn’t a bad career move for me.

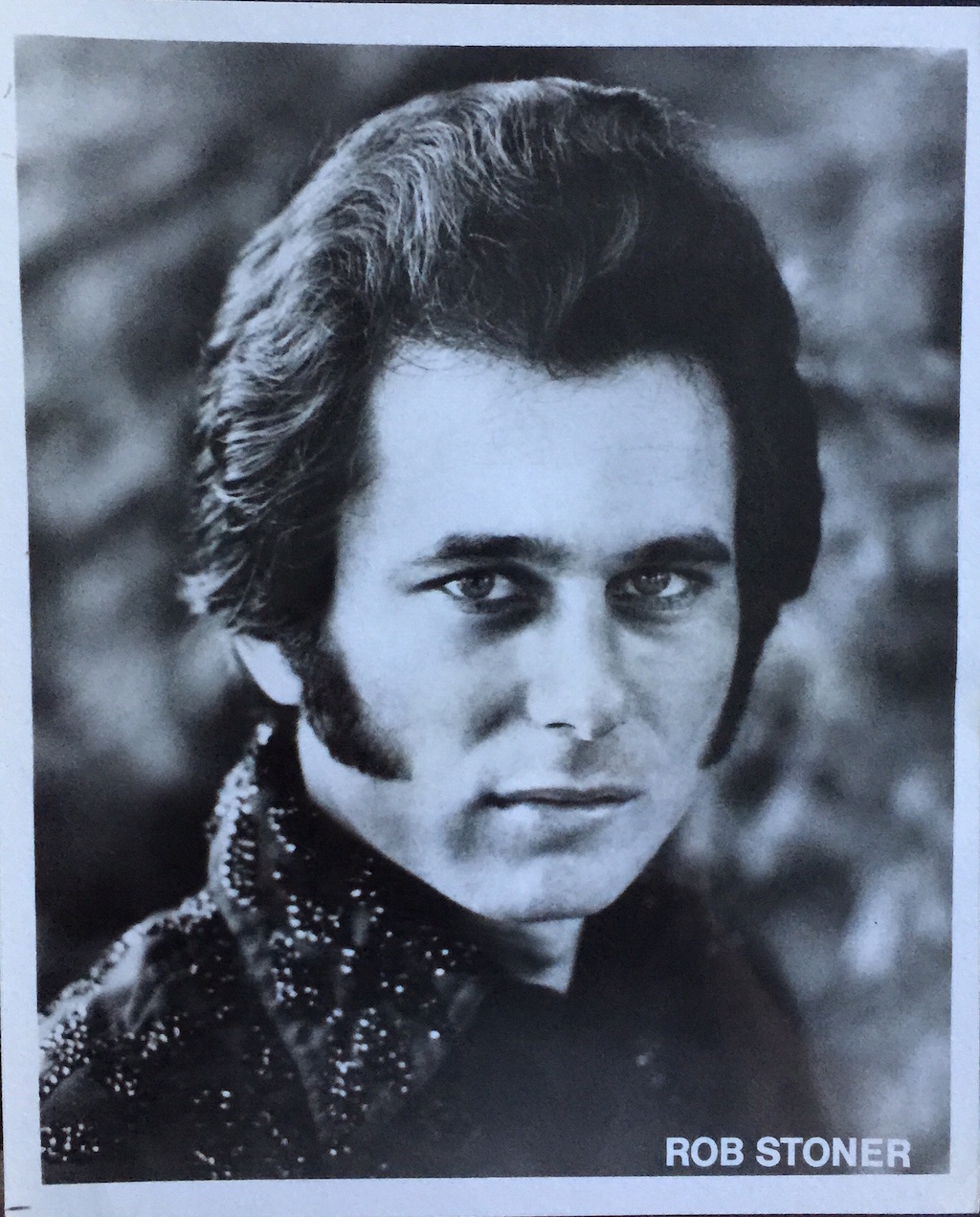

As a “Rockabilly” Artist

RS:I recorded some singles in Nashville, and got some airplay, but it really didn’t change what I was doing on the club circuit with the band.

How did you hook up with Dylan?

RS:Dylan had stayed in touch since we had first met in L.A. in 1972. During the Summer of ’75, Bob was hanging out at the clubs on Bleecker street and trying out new material on unsuspecting bar patrons. He had enjoyed great success with Blood on the Tracks (see text at note 1 of Never Say No To a Rock Star regarding the recording and re-recording of that album). Although there were several releases in this period–Planet Waves, Before the Flood and The Basement Tapes, The Band had quit his employ after finding success on their own. At that point, Bob was searching for something different; he was working with Jacques Levy, a psychologist, playwright and director/lyricist. (Levy had written and directed Oh! Calcutta!) The two had met through Roger McGuinn of The Byrds.

If you remember, that first Byrd’s album covered several Dylan songs and gave Dylan a level of visibility outside of the “folk” scene- he became a “pop” star as a result. Bob would come into a club, and there I’d be, onstage backing up Tim Hardin, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott or whoever. At one point, Dylan asked me if I could do 10 or 20 minutes to open up a show for him, but I didn’t think he was serious. Dylan knew I would be a good opening act because he had seen me “work a room” a few times and keep the audience’s attention. But, everything was left pretty vague; it was like “let’s do something sometime.”

That “something” turned out to be the album Desire and the Rolling Thunder Revue.

(To be continued….)

Bill Hart

December 5, 2016

_____________________________

Photo credits:

Head shot & Rob on TV with Don McLean: Grace Rothstein

Band photo: Arthur Rothstein

Link Wray, Rob and band: Bruce Bennett

by arrangement with Rob Stoner.

[1]See http://www.folkways.si.edu/woody-guthrie/dust-bowl-ballads/american-folk-struggle-protest/music/album/smithsonian. Rothstein père eventually joined LOOK Magazine and was its director of photography at the time the magazine ceased publication in 1971. For more on Arthur Rothstein’s work, see arthurrothstein.com.

_________________________________________________________

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.