The Art of Recording: A Conversation with Brooks Arthur

Janis and Brooks at the board-Between the Lines sessions, courtesy Peter Cunningham

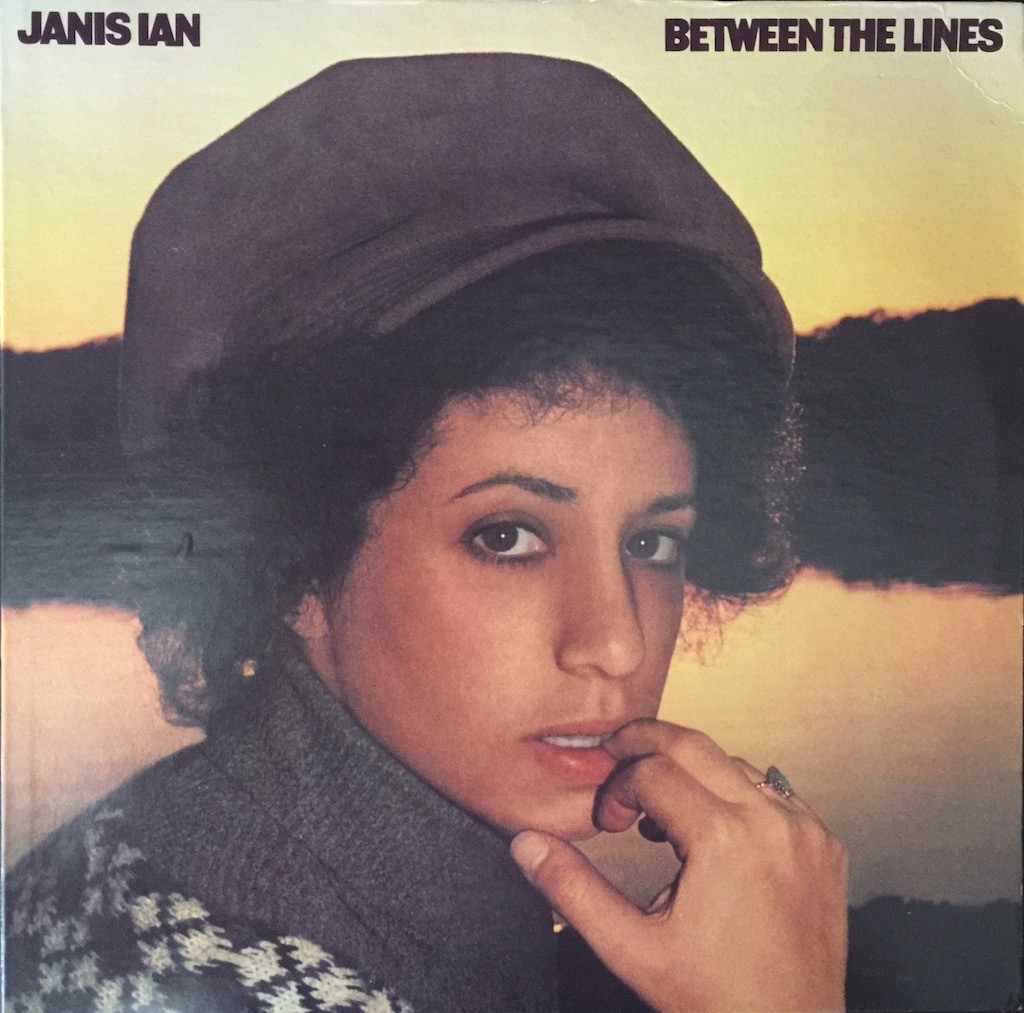

Brooks Arthur still dreams of the little studio he owned in Blauvelt, New York in the early ‘70s; a converted gas station on a suburban highway next to an all-night diner in “upstate” New York. 914 Studios (pronounced: “nine-one–four,” the telephone area code there at the time) may have been one of the best sounding rooms Arthur recorded in. He ought to know: a songwriter and performer with ties to the Brill Building era, Arthur has engineered many famous records, including Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, created the audio frame-work of some of Springsteen’s earliest, best work and enjoys hundreds of technical and production credits over more than fifty years: from Phil Spector-produced pop and early Van Morrison, to early Springsteen, Janis Ian and Neil Diamond, to mainstream artists like Liza Minnelli and Bette Midler. Brooks’ business partner for a time- Phil Ramone, who produced and engineered some of the best records ever made –recruited Brooks for his “ear” and skill. Over the years, Brooks Arthur has worked with everybody, from legends like Dusty Springfield and Marvin Gaye to Peggy Lee and Marvin Hamlisch. One of these records—Janis Ian’s Between the Lines—has been a perennial of mine since it was first released in 1975. Between the Lines is a touchstone for me, musically and sonically. [1] It was recorded at 914 Studios.

The fact that this studio was located just a few miles from my New York house has also fascinated me ever since I moved to Rockland County in 2003. It is a bit of an urban legend in these parts. By the time I got here, the studio was long gone- there were pieces of its history on the web, and mentions of the place in album credits. A flurry of press about the studio appeared recently: the Rockland County Historical Society has formally recognized 914 Studios as a landmark of our American musical heritage.

I’ve been chasing Brooks Arthur for an interview for a few months- not that he is elusive- he’s just really busy! My aim: to get an understanding of why a great recording sounds great, from the man who produced and engineered it. At the time of the recording, Arthur had a longstanding creative relationship with Ms. Ian and had built the studio where the recording was made. I figured this might help provide me (and readers) with some insight into the process of making a great recording. Interviewing Brooks is also fun- he’s smart and there is a joy he communicates across the telephone line from the West Coast that transcends time, distance and the vicissitudes of life. He’s a charmer, warm, funny and quick-witted.

Why Blauvelt, New York?

Brooks Arthur (“BA”): I was working with Phil Ramone, who brought me into the A & R Studios “empire” where I became his business partner. Like most major cities, Manhattan is fast, expensive and unforgiving, only more so. It wasn’t very conducive to artistic contemplation, though- and there were a number of things happening at the time that made going “upstate” a sensible move. A lot of artists did not live in Manhattan; they were in places like Woodstock, where Albert Grossman’s studio was a center of gravity for musicianship at the time. I also wanted to experiment with a different model for recording — an “artist’s workshop” approach — which was the exact opposite of the fast moving, big metropolitan studio business scene.

What did that mean in terms of your working with the artist?

BA: Time, money and food – I wanted to slow the pace, give the artists some breathing room, keep the costs down and give them an opportunity to work in a more relaxed environment. I found this garage building on Route 303 in Blauvelt that was the right size- it obviously needed to be built-out as a studio but one of the keys to success- and this sounds silly- was its location. Next to a 24-hour diner. Musicians like to eat, just like real people. Given the work schedule of composing or recording or mixing—it isn’t easy to get food at any hour. The diner was a constant in our lives there.[2]

The location today. A plaque is to be installed by the Rockland County Historical Society recognizing the historical and cultural importance of 914 Studios.

So, you built the studio pretty much from scratch?

BA: Yes, we sealed up the double bay garage door area, laid new flooring and did the necessary acoustic isolation and treatments. It was essentially a concrete shell with a floating floor- ideal for a recording studio design. The garage bay area became the session room, which was big enough to bring in a large piano, timpani, set up a large string session; there was a set of double doors on the side that allowed us to move larger instruments in and out of the room easily.

We also had access to a lot of resources through A & R- they had connections to top acousticians, had an interest in the company that manufactured the mixing board (a SUBURBAN SOUND INC 16- track board) and we brought in a number of good tape machines and other ancillaries.

Though this was a small studio in the country, I went to the trouble to get it right. A friend test-played a variety of Steinways to pick “the one” we bought for the studio. The goal was to get a good sounding room with the right gear without being unnecessarily extravagant.[3]

What I wound up with was a really “pristine” sounding room. You could hear anything that was “off”: a noisy, or lower quality sounding guitar amp was immediately obvious. The room was revealing, but it wasn’t cold or bright sounding, it was intimate and since I knew every inch of it, I could control the sound I got there- with reverb units I could get spaciousness, and make it sound like a huge room.

Was the gear mostly solid state given the time period?

BA: It was an assortment that was probably common to the era; we had tube compressors, used some tube microphones, including the most delicious sounding Telefunken U-47- it was an ethereal sounding mic and the one of choice for Janis’ vocals. We also had a few other gems- Telefunken U-87s, which were very rich sounding and perfect for strings. I also had a “secret weapon” I used on drums and toms: Altec “Salt Shakers.” I have been using these vintage Altec 633s since the day I started engineering at Dick Charles Demo Studios in Manhattan.

We could mix and match to get the “warmth” of tubes. The Suburban Sound board was not tube, but it had a unique sound; Neil Muncey, who built them, used Melcor op amps.[4] That board had a sound of its own.

Photo of Suburban Sound board featured at 1970 AES Convention, Dub Magazine, Nov. 1970.

Combine that with the sound of the room, those tube mics, my ears and help from two young assistants (who went on to be all-star engineers), we had an enviable formula. Since we were recording to tape, which has a characteristic warmth and sonic pliability, we achieved a lot in a relatively small studio: we had a 16 track Scully 2 inch machine and a 4-track Ampex. I attached the 4-track through my patch bay to the EMT chamber to create a slight echo delay reminiscent of the Columbia Records studios. The sound was elegant and smooth but still brilliantly contemporary as echos go. I also used a pair of 2-track machines which were the real workhorses: I used them for mix-down and for “slap-echo,” a sound that you’ll immediately recognize from those captivating, traditional ‘50s era country records.

Can you tell us about the sessions?

BA: I knew Janis from Society’s Child. She is a great songwriter, a great performer and is a perfectionist. Carole King’s Tapestry— probably the most popular female singer-songwriter albums of the time, had gone off the charts. That was a truly great record, but Janis was very different: she had the writing chops and was a truly gifted talent, but inspired a whole different mood than Carole King.[5] I also felt like I had been kicking around for a while- doing good, notable stuff, but I think there was this feeling that Janis and I shared- that this was “our time” to really knock it out of the park.

We worked on the album for several months. Janis would sketch out a song and we would have these pre-production meetings to decide what songs to use.

Ron Frangipane, who was responsible for the string and horn arrangements, was part of the team. But I babysat every chart. I didn’t want to lose Janis’ folk-like quality by over-orchestrating, but I was a sucker for a romantic or telling string line. Janis was also involved in the arranging and had a lot of input on the record, for obvious reasons. We laid down the basic tracks, and each night, I would do a rough mix to get a sense of where we needed to go next.

Janis, Brooks and Larry Alexander, engineer (and percussionist on the album), courtesy Peter Cunningham

What made this recording “sing” like it does?

BA: Some people I know joke that it was all “the room.” But I worked hard on the recording to get it to sound intimate and spacious at the same time. A lot had to do with microphone placement and the mix, including decisions on panning: where the drums were placed in the mix, which guitar was panned to what side to give the recording dimension. I would do similar panning tricks with echo. That’s where my rough mixes each night paid off; to guide me to the next step. It’s a fairly complex recording, and we wanted it to sound intimate, have the benefit of instrumentation without sounding cluttered.

What about overdubbing?

BA: Sure, we took advantage of that, the string parts were overdubbed later, and the horns were overdubbed even one step after the strings. I treated the string section of 20 plus players as if they were a single instrument, like a human voice. That gives you a little insight to what I was listening for when we were recording and mixing these parts.

Keep in mind that we “only” had 16 tracks. That forced certain decisions about how to design the sessions and the mix because eventually, we would run out of space. So, we would pre-mix certain elements; at that point, we were committed. It required some experience, some decision-making and a few prayers! I had enough confidence and skill to do this well but it was another aspect to recording that could be challenging: to know how those pre-mixed sessions would fit into the overall mix and take account of that.

The record has a lot in it, in terms of instruments, horns, strings, but it doesn’t sound overproduced, the way some records do.

BA: Thanks. (Silence)

Seriously, at the time we were doing this, the gold standard (really multi-platinum, eventually) was still Tapestry. It was spare, Carole King is not only a great writer, but knows where to put the emphasis. Between the Lines is really about Janis, her songs, her voice, her sense of emotion, and I didn’t want to overwhelm it with lots of “production.” But, at the same time, we wanted it to be rich and varied. Some of the songs are more “produced” than others, but I think they justified it. And by listening to all of those strings as one instrument, you can better hear where they belong in the mix. I cared enormously about this record (as did everyone who was part of it) and that is reflected in what you hear.

The album was originally mastered by the legendary “RL” (Robert Ludwig). How did that come about?

BA: Bob was already at the top of the game by the time he mastered Between the Lines. I chose him to do the mastering; he was a regular part of the team that A & R used, I knew Bob and I think he was pretty happy with the results. I certainly was, and Janis was too, as I remember.

The standard issue pressing from Columbia sounds fabulous. I mentioned that I have a bunch of copies, including a test pressing.

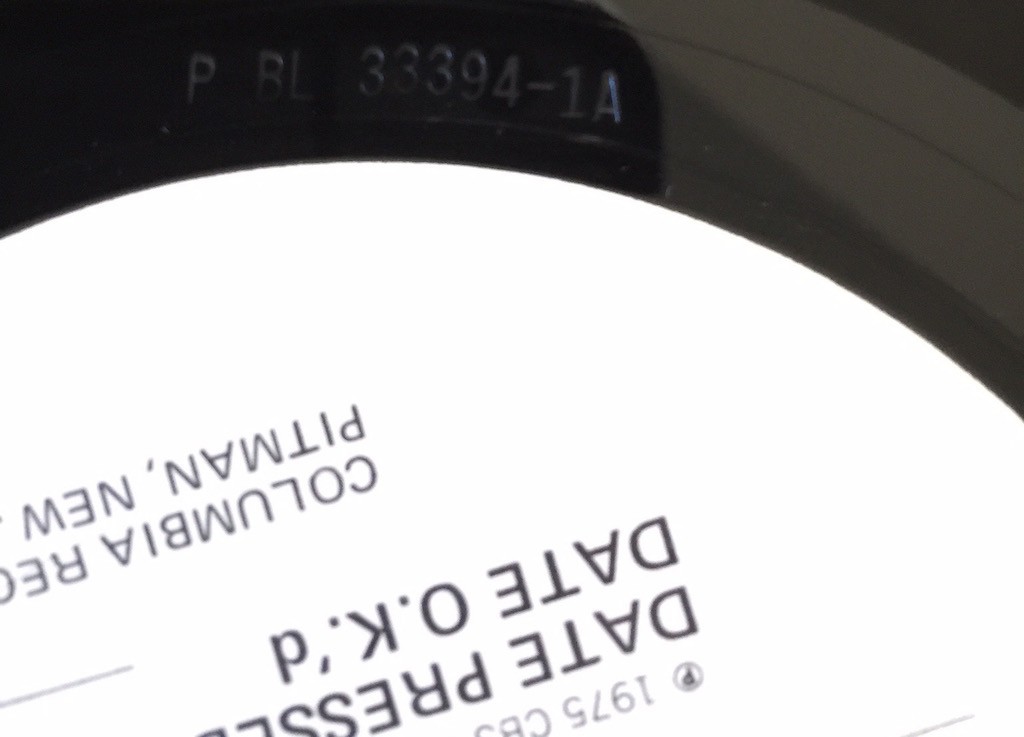

Test pressing of Between the Lines, Columbia, Pitman N.J. plant, inscribed ‘RL’. See deadwax below for inscription, which can also be found on commercially issued copies.

The record you could buy off the shelf basically sounds the same- consistent, neutral but lively, a little of that analog “warmth” but not overly soft, great clarity and lot’s of contrast, texture. It really is, to my ears, an almost perfect recording if there is such a thing.

BA: Nice of you to say so. Janis won a Grammy for “At Seventeen” and the album reached #1 on the charts. So, I guess we did good. Looking back, Janis should have won “Best Album of the Year” as well. It went to Paul Simon and Phil [Ramone] for Still Crazy After All These Years. It’s funny- Phil and I were glaring at each other and smiling at the same time from our seats in the theatre. Paul and Janis were exchanging glances and dreams in the seconds before the winner was announced.

But that was it. Last record done at 914?

BA: Not exactly, but close. There were lots of business issues, the economy was a mess, we were still in the energy crisis, and the business was undercapitalized. Phil [Ramone] was stretched thin- he was in huge demand, and had so much going on. We started work on Springsteen’s Born to Run– the title track was recorded at 914. We also recorded an earlier version of “Jungleland” and a few other tracks at 914 Studios, though when the production moved, those were re-recorded. I think an early version of “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” was done at our studio and another beauty, “She’s the One” that were stunning. But the production moved when Jon Landau took over and most of that was redone, except for the title track. The version of the title track on the album is the one recorded at 914 Studios.

Neil Diamond wanted me to come west to work with him, and the time seemed right. I sold the studio and moved to the West Coast. My last memory, walking out the door of 914 Studios for the last time, was hearing strains of song “Born to Run” being worked on in the studio. It’s not a bad memory!

My thanks to Brooks Arthur for giving us his time and reflections on the making of a truly great record, and to Brooks, Janis Ian and all the folks who made this album so special and enduring. Brooks Arthur’s website is: http://www.brooksarthur.com/index.html (While you are there, check out Brooks’ discography, it is mind-blowing!).

An additional thanks to Peter Cunningham who, running between four cities in three days, still found time to pull up those great photos of Janis, Brooks and Larry Alexander. Peter is a world-class photographer who has captured the image and spirit of many greats. His work can be found at: http://petercunningham.photoshelter.com/#!/index

And a nod to Rockland County, which is, in some ways, a timeless place. It is still the country up here despite its proximity to Manhattan and remains home to generations of writers, performers and other creative artists.

Stained glass artwork of 914 logo by Hallie Coletta, courtesy of Brooks Arthur.

Bill Hart

Nov. 16, 2015

______________________________________

[1] I heard Ian perform in 1975 at the time the album was released. I return to this album often, not only for the music, but also as a reference “check” for my system. It contains all the elements: single female voice, horn parts, string arrangements and a clean neutral sound that is neither too warm nor overly analytical. It has been one of my benchmark records since its release. That Robert Ludwig originally mastered it doesn’t hurt either. More about that below.

[2] The Blauvelt Coach Diner is still thriving. For what it’s worth, the legendary “Sun Studios” in Memphis (actually, Memphis Recording Service), was adjacent to a restaurant where Sam Phillips conducted business meetings because the studio itself was tiny.

[3] Some of the big studios of the era were being built or reconfigured to accommodate more modern (rock) music culture: hot tubs, lounges, and a sort of “luxe” environment that was inviting rather than clinical. That cost money, and added to the overhead of studios operating in Los Angeles and New York.

[4] My fractured history of this era: an op-amp is a type of device that dates back to the golden age of tubes. In more modern applications, these were hybrid or solid state devices. Think of the op-amp as a primitive type of integrated circuit. They are still in use today. See Jung, et al, Op Amp History. Depending on design and implementation, they can have a very vivid, beefy sound without sounding edgy or bright. Any gear-heads that want to weigh in on this and have knowledge of these boards – write to Letters to the Editor here and I can publish your contribution.

[5] Editor: Tapestry has a homespun, spare quality that was so refreshing at the time and remains a classic because of it. Ms. Ian’s work on Between the Lines is darker, more urbane sounding- though King was a Brill Building writer in the golden age, it is more upbeat, California-influenced; Ian captures a different quality; the longing and loneliness take you to a different place. Think of Manhattan early in the morning when the streets are empty. Two very different records by two very gifted singer-songwriters. I do think that Between the Lines is the better recording, sonically.