The Finish Line for Your Phonograph Stylus…

By Mike Bodell, May 23, 2019

Based on an informal survey of friends who predominately play vinyl records, I believe the most neglected part of their audio system is the stylus on their phonograph cartridge. The stylus is a key component in an audio system and is subjected to the most wear. Yet when I asked folks in my network how many hours of play their cartridges have seen, they could not tell me with any accuracy; all ventured educated guesses. I’ve been there too. Given the value of records today, particularly rare and collectible jazz records, it is astonishing that more care is not given to understanding the condition of the diamond stylus. That recognition led to this article, where I will examine the critical issue of stylus wear as it pertains to useful life and the potential for damage to records.

In his 1954 booklet The Wear and Care of Records and Styli (Climax Pub. Co., New York, pp.56), babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015017575856;view=1up;seq=5 (courtesy of HathiTrust), Harold Weiler states that research shows the majority of listeners were damaging their valuable record collection through continued use of worn styli. He goes on to suggest that listeners were introducing considerable distortion into otherwise excellent audio systems. He writes, “It was a revelation to discover that even those who had acquired expensive fidelity reproducing equipment, were not entirely aware of the important part played by the stylus in record reproduction and record wear.” Honestly, little has changed.

My research on stylus wear was driven in a large part by a desire to better care for records in my own collection, i.e., to do no harm with a worn stylus. Unfortunately, I’ve discovered that no consensus exists within the vinylphile community, nor even among manufacturers of phono cartridges on how many hours of play wears a modern natural diamond stylus to the point where it should to be retipped or replaced. In my research, I found that some experts say stylus lifetime depends on stylus shape, tracking force, and the condition of the vinyl among other variables, while other experts claim that tip shape makes no difference to stylus life. We are talking about the fundamental physics or at least empirical evidence of wear by a shaped diamond at a tracking force sliding in a vinyl groove at variable speed. The physics—the physical processes and phenomena of this particular system—should be well known. Yet in my survey, I’ve seen estimates of stylus life ranging from 300 hours to well over 3,000 hours of play. I know someone who has at least that upper number of hours on his cartridge without a retip; he tells me it still sounds great.

It is important at this juncture to distinguish between stylus wear that causes barely audible distortion, and more significant wear that damages the record grooves. All styli cause some level of distortion due to their inability to track the record groove exactly as the record-making cutting stylus created it. As stylus wear progresses, this distortion increases, and eventually rises to a noticeably higher level than when the stylus was new. Some vinylphiles will replace their stylus at this early point, while others are less sensitive to these minor distortions and continue using the stylus until the distortions are much more obvious. Unfortunately, at that later point the stylus is likely causing damage to their records. Perhaps the optimal time to replace the stylus is sometime between these two points, and this may explain the wide discrepancy in stylus lifetime recommendations from cartridge manufacturers and other industry experts. This article attempts to find that optimal point.

The maximum number of play hours for advanced stylus shapes that most folks suggest from my reading of dozens of audio forums and many on-line resources is approximately 500 hours on the conservative side and 800 to 1,000 hours on the aggressive side. These non-scientific estimates are significantly lower than the 1,500 to 3,000 plus hours touted for advanced stylus shapes, even among current prominent cartridge manufacturers. Ortofon, for example, publishes on their website that the maximum life for their Shibata-tipped stylus is 2,000 hours. I called Ortofon who cautioned me that by 1,000 hours the cartridge should be examined. Clearaudio recommends in their owner’s manual checking the stylus tip for wear at 500 hours. They also write that the stylus should be replaced after approximately 2,000 hours of use, or sooner if excessive wear and tear is suspected. Audio Technica recommends for their micro line tipped cartridges replacement at 1,000 hours. Nagaoka, a well-regarded Japanese cartridge and stylus tip manufacturer is blunt on its elliptical and line contact options, “…for general use at home, the reference time is between 150-200 hours in which the stylus begin to wear and the tone quality deteriorates. Recommend replacing the stylus as early as possible to enjoy clear tone…and not to damage the disc grooves.” Other well-known manufacturers make no mention of stylus life for their cartridges on their websites and even in user manuals I surveyed.

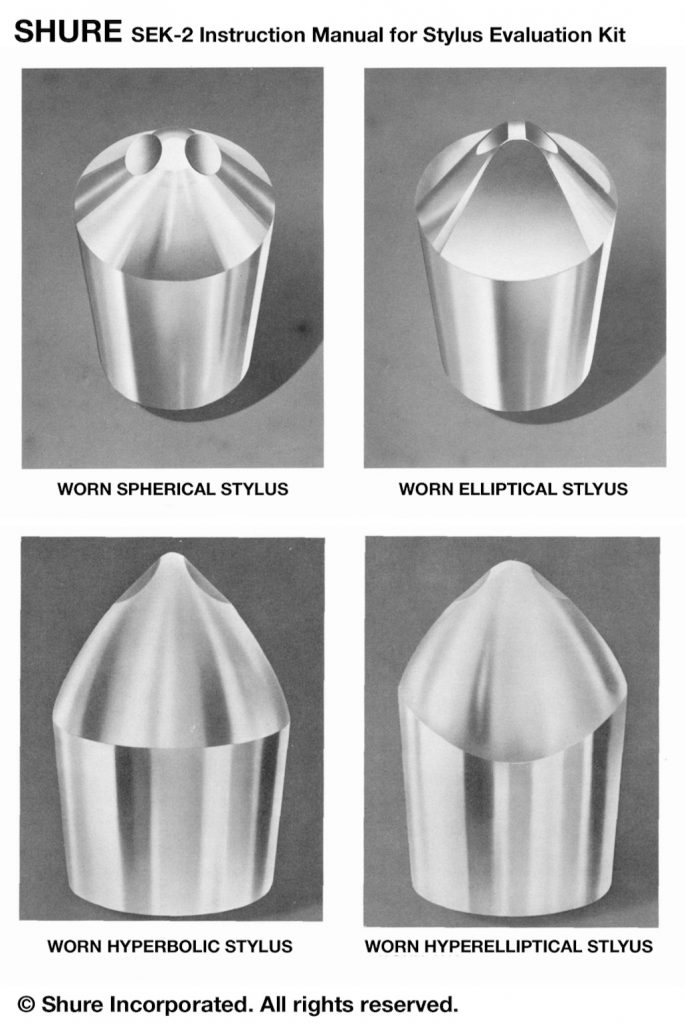

I’ve seen photographs and illustrations of severely worn styli that take on a chiseled profile at the sides of the stylus tip. As the stylus tip ultimately develops a flathead screwdriver shape it in turn begins to damage vinyl grooves but the needed data to understand when that occurs is not readily available and is sometimes even considered confidential. Manufacturers by and large are silent about critical stylus wear, so the burning question remains: when does that occur?

Industry Experience

In the 1960s, the director of Disc Research at CBS Laboratories, Arnold Schwartz, had a team studying the effects of worn styli on playback distortion (from his article “The First Component Of Your Hi‐Fi System—Your Phono Stylus,” published in 1972 by Micro-Acoustics Corporation). Columbia Records had a quality control (QC) procedure to play one record from each spindle of newly-pressed records to ensure the stamper had not been compromised nor developed a defect. In the process, QC testers discarded a stylus when it no longer sounded “right,” allowing them to focus on stamper quality.

On examination of these discarded styli, Mr. Schwartz was surprised to discover that only very minor flat spots had developed on the sides of the diamond tip. Under a microscope the stylus wear—seen as small bright “cat’s eyes” in reflected light—was barely perceptible, even with sophisticated microscopes. He therefore was quite skeptical that these styli were actually worn out, regardless of what the QC testers said. The record pressing plants typically had no mandatory visual inspection process for rejected styli; QC testers developed the practice based on what they heard. But new styli meant higher QC costs.

Since visible stylus wear was minimal, Schwartz decided to interview the QC testers. To his credit, he understood that when the job was to listen to records all day long and pick out those that don’t sound right, listeners developed an acute sensitivity to deterioration in sound quality. The QC issue was either in the stamper, meaning the potential to ship a poor-quality record, or in the stylus, which could be replaced.

One QC tester provided Schwartz with a convincing demonstration with a discarded stylus he brought back to the plant. Without this tester looking, Schwartz swapped numerous times a good stylus with the very slightly worn one. Each time, by the presence or absence of distortion, the tester could instantly tell which stylus was installed. By the end of that session Schwartz himself could readily tell the difference. He was hearing high frequency distortion, as manifest in a worn stylus.

When asked when to replace a stylus (and/or today to get a cartridge retipped), Schwartz said, “…when you hear distortion.” Honestly, that is not particularly helpful to most of us. Few can remember how a brand-new stylus sounded compared to after 500, let alone 2,000 hours of wear. Distortion develops as an extremely slow incremental change. This change is so progressive that few among us have the auditory memory to appreciate the difference until it has become so severe that damage to records is already occurring. Therein lies my issue. I don’t have perfect pitch golden ears, yet wish to avoid reaching the point where damage has been done.

Stylus Diamonds Are Not Forever

In his 12 April 1996 New York Times article “Stylus Diamonds Are Not Forever,” Hans Fantel also suggested listening for playback distortion to indicate the time to change a stylus. He recommended playing the inner grooves of a pristine record of specifically a female vocalist with clear diction. If the old stylus made the singer seem to hiss and spit, that ‘sibilance’ is the earliest possible evidence of a worn stylus. What makes that marker a bit tricky is that some music was poorly recorded in the first place, and sibilance is on the recording.

Mr. Fantel goes further, noting that microscopic studies show noticeable wear on a diamond stylus after about 500 hours of playing time. The amount of damage that level of wear inflicts on records is minimal initially, according to Fantel. Yet the damage caused by continued play of the same record with only a slightly worn stylus is cumulative and soon becomes noticeable as a “harsh, gritty” sound. After about 1,000 playing hours, Fantel asserts, the rate of destruction to the vinyl accelerates, as eventually the diamond is honed to form edges that ream the record groove “like a plowshare.”

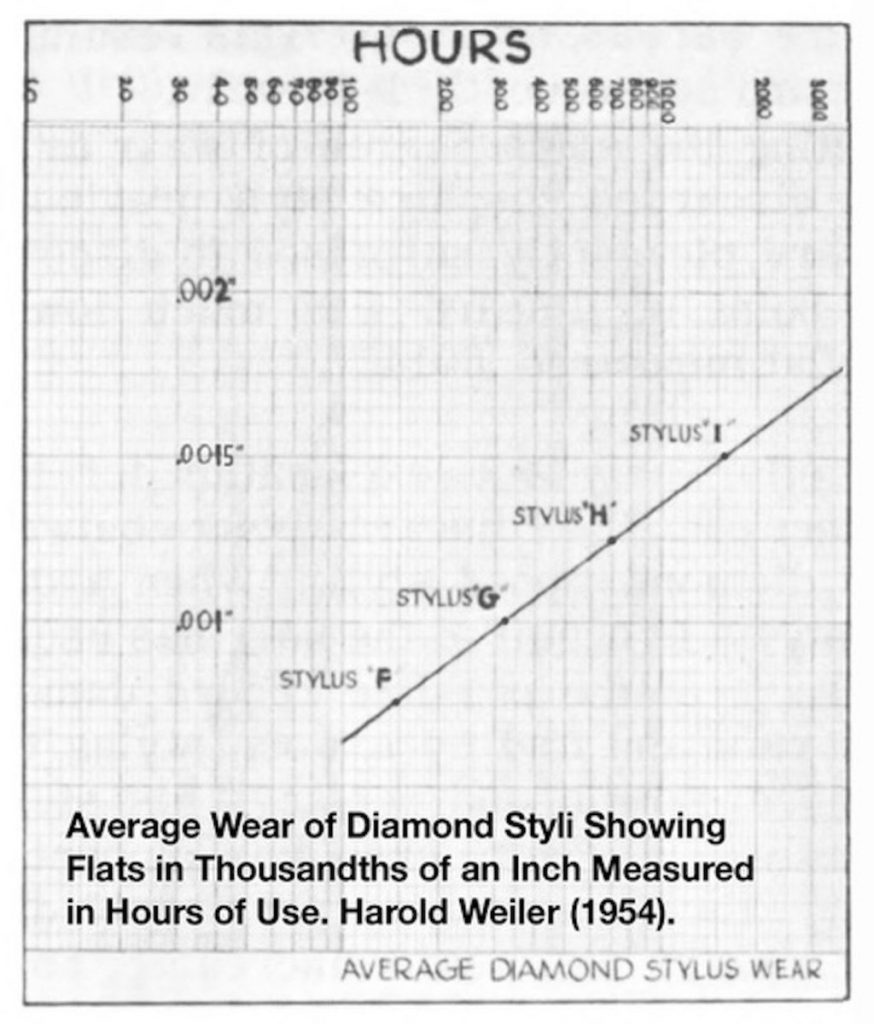

In The Wear and Care of Records and Styli, Harold Weiler illustrates wear as seen through a microscope on spherical (or conical) shaped diamond styli, versus hours of record play. Based on his experiments, Weiler determined the rate of wear of a diamond stylus to the point of extreme groove damage. He tested on 12-inch vinyl records introduced in 1948 in mono and played at 331⁄3RPM (stereo came in late 1957). The standard mono stylus at the time measured one thousandth of an inch (1.0 mil) at its longest radius. All of his empirical tests were conducted at 7.0 grams of vertical tracking force (VTF). He calculated that this high VTF applied to the small contact area of a spherical stylus was up to 26 tons per square inch. Arguably, this early work is dated, yet Weiler’s methodology is still sound. To be sure, modern advanced cartridges are designed with greater initial record groove surface area contact and typically use much lower VTF, ranging from 1.5 to 3.0 grams.

Harold Weiler (1954) repeatedly played phono cartridges with a spherical-shaped diamond stylus to gauge cumulative wear. He noticed that flat areas developed on the sides of the stylus tip. As hours of play rose, the flats increased in diameter and the tip began to lower in the record groove. As flats developed, distortion in playback began, initially at the high frequencies. At some point, the flats were large enough that the tip was no longer constrained by the record groove. That caused damaging record groove wear.

Through detailed research, Weiler found that after 145 hours of play (~430 record sides), flat spots of .00075 inches were worn to each side of the diamond stylus tip. These flats would increase in size to .001 inches and .00125 inches after about 300 hours and 700 hours of play, respectively. The flats would reach .0015 inches at ~1,500 hours of play, or play of ~4,500 record sides. According to Weiler, flats of that size resulted in overall reduced tonal response, high noise level, greatly increased distortion, and considerable record groove wear.

Correlating flat sizes with playback performance, Weiler noted that with flats of only .00075 inches distortion, while barely perceptible, had already begun. Flats measuring .001 inches from just over 300 hours of play resulted in noticeable distortion on a violin solo, a soprano, a flute, and in higher pitched instruments. By this point flats were well-defined and prominent enough to be seen under a decent microscope. The flats were large enough at .00125 inches—700 hours of play—that the stylus could not be controlled by the sides of a vinyl groove.

As the flats enlarged with wear, more of the stylus tip surface area was exposed to the record groove, thus lowering the loading force per unit area. The tip, however, would begin to develop a chiseled profile and start to ride the bottom of the groove. The bottoming out by the tip caused much greater groove wear and considerable distortion in sound reproduction. Weiler concluded, “We can now definitively state that a certain number of hours of play on the equipment used resulted in a specific and predictable degree of stylus wear.”

Granted, the studies performed by Weiler involved larger spherical styli, but this same stylus wear on modern equipment is seen clearly in a series of WAM Engineering photomacrographs in Michael Fremer’s twin articles “Stylus Wear And What to Do About It” from 25 July 2012 and “What Does Stylus Wear Look Like?” from 28 August 2012 published on website Analog Planet. From the “front-on” images in those articles you see wear on a variable-radius line contact nude diamond. A critically worn modern stylus tip still descends deep into the record groove, risking at some point groove damage. Obviously, turntable, tonearm, and phono cartridge designs are more sophisticated today than they were in the mid-1950s when Harold Weiler was figuring out how ruby and diamond styli wore with increasing hours of use, yet the same physical processes are involved. As a consequence, Mr. Fremer advises that clean records are critical to minimize record wear and to optimize stylus life. In this case, at 1,000 hours, the stylus tip was overdue for retipping.

“We can now definitively state that a certain number of hours of play on the equipment used resulted in a specific and predictable degree of stylus wear.”

Nearly 60 years earlier Weiler offered that the primary cause of stylus wear was dirt embedded deep in the record grooves. According to his analysis, this dirt consisted of 12% silica particles, 35% diamond dust worn from the stylus during use, 40% miscellaneous particles that included soot, undefined grit, and particles worn from the record groove itself. The remaining 13% consisted of fibers and lint. Today, both vacuum and ultrasonic record cleaning machines allow vinyl lovers the best possible options to remove dirt from grooves to maintain clean records.

Several classes of improved stylus tip shapes have been developed since the classic spherical tip tested by Weiler. Today, stylus tips come in elliptical, hyperelliptical (e.g., Shibata, line contact) and Micro-Ridge shapes. A modern spherical stylus tip generally has a ~0.7 mil radius for a smaller contact with the record groove wall. This shape is the least expensive and still the most widely used today. The dual radii elliptical stylus shape makes greater contact with groove walls for more precise tracking and improved frequency response. Hyperelliptical tips are an improved elliptical design for even greater groove contact. When properly aligned, these styli offer superior high-frequency response, improved tracking, reportedly longer tip life and reduced record wear. The computer-designed Micro-Ridge tip resembles the cutting stylus on the lathe used to produce acetate master disks in vinyl record production. When aligned correctly this shape is capable of the best high-frequency performance with reportedly extended stylus life and the least record wear.

For an excellent primer on the pros and cons of stylus tip shapes, see “Stylus Shape Information” published by SoundSmith under the ‘How To’ tab at www.sound-smith.com/articles/stylus-shape-information. SoundSmith is a well-regarded phono cartridge designer and manufacturer. The firm is also one of the few U.S. companies to offer stylus retipping services. Another in-depth discussion on stylus tip shapes is on Vinyl Engine, Board index, Hardware, Cartridges and Preamps, see the thread “Advanced Stylus Shapes: Pics, discussion, patents.”: www.vinylengine.com/turntable_forum/viewtopic.php?f=19&t=22894.

Advanced stylus shapes are specifically designed to increase record surface contact to trace high frequency details without bottoming the stylus in the groove. An excellent on-line paper, “Gramophone styli and groove geometries,” by Richard Brice, published by Pspatial Audio, under Help topics, Historical and Theoretical Background (pspatialaudio.com/stylus_grooves.htm) deals with the technical aspects in the evolution of stylus tip design. Moreover, the paper addresses the forces exerted by advanced tip shapes on vinyl and why these shapes require a very clean record. To optimize performance and stylus life, the advanced shapes also require more precise cartridge and tonearm alignment to set up properly. Another downside to most high-end ‘moving coil’ cartridges is the stylus must be retipped or replaced since they are not designed for simple plug-in replacement for primarily ‘moving magnet’ types. Notwithstanding these limitations, the question of hours of stylus use before a cartridge should be retipped or replaced remains largely unanswered.

Debate continues to rage within the vinylphile community on the impact of stylus shape on record and stylus wear. Literally opposite claims persist in regard to record wear from spherical styli due to their limited initial contact area of the diamond tip. Oliver Read and Walter Welch unwittingly address this debate in their 1976 book, From Tin Foil to Stereo: Evolution of the Phonograph (Howard W. Sams, Indianapolis, IN, pp.550). The book features highly detailed electron microscope images of record wear between different spherical and elliptical styli at varying tracking forces. Those images came from Dr. J.G. Woodward, et al. in work performed at the RCA Laboratories (see “The Role of the Scanning Electron Microscope—A New Tool in Disc-Recording Research,” published by Audio Engineering Society [AES], Vol. 16, pp. 258-265, July 1968). The research showed that spherical styli, with their limited contact to the record groove walls, produced the least damage to records under lighter tracking forces. Using the same technique, Mr. G. Alexandrovieh showed how a Shibata-tipped (line contact) stylus is capable of creating a unique type of damage, if the tip itself is damaged. That finding was presented in his paper at the 58th Convention of AES on Nov. 4-7, 1977, “Role of Scanning Electron Beam Microscope in Disc Recording.” With these conflicting results, I am now officially confused.

Shure Can Pick ‘Em

Shure Incorporated, founded in 1925, pioneered numerous cartridge designs beginning in 1937. Shure products aimed to maintain maximum stylus contact with a record groove while using a lower tracking force to ensure record preservation. Shure made phono cartridges until 2018, when the company exited that product business. For a period, Shure was the largest manufacturer of phono cartridges in the U.S.

Shure offered that with in-home use a stylus is worn out in 600 to 800 hours. Without differentiating tip shapes, Shure recommended replacing a stylus when total playing time was over 500 hours. Shure also recommended stylus replacement if audio quality was poor, meaning the advent of distortion. Moreover, Shure recommended replacing any stylus showing serious wear when examined under a microscope.

The company made available to its dealers an evaluation kit that included a microscope with 200x optical magnification. They provided dealers with instructions on how to test customer systems, specifically in stylus inspection, seen here: Shure Stylus Evaluation Kit(pubs.shure.com/guide/SEK-2/en-US.pdf). The guide included diagrams and photomicrographs of both good and worn tips for spherical, elliptical, hyperbolic and hyperelliptical tip shapes. Unfortunately, in the Amazon age that brick & mortar shop is all but gone, so what’s a vinylphile to do?

Harold Weiler (ibid.) noted that diamond styli developed tip wear that he called flats that ultimately introduce playback distortion and eventually record wear. He learned that styli have a useful life based on number of hours of play.

During the time of Weiler’s research, Shure was fast becoming the largest U.S. producer of phono cartridges. Shure developed increasingly sophisticated stylus tip shapes that increased surface contact with the record groove and lowered the required tracking force for proper playback. The company also noted the impact of tip wear on a record groove and developed a kit for their dealers to gauge the level wear on phono cartridges. Dealers would use a microscope to check for the chiseled shapes of critical wear on a customer’s stylus.

To support their recommendations, Shure conducted comprehensive research on phono cartridges, specifically on stylus wear for various advanced tip shapes. Shure presented their phono cartridge research in a technical seminar in 1978 in New York City. The seminar proceedings are available here: www.shure.com/en-US/support/find-an-answer/high-fidelity-phonograph-cartridge-technical-seminar. Research by B.W. Jakobs and S.A. Mastricola from 1972 to 1977 is compiled in their paper, “The Stylus Tip and Record Groove—The First Link in the Playback Chain.” The researchers conducted many tests to estimate stylus tip life and to evaluate the effect of various parameters on tip wear, including evaluation of spherical, biradial (i.e., elliptical), and hyperbolic (i.e., hyperelliptical) classes of stylus tip shapes.

This work revealed two important findings on stylus wear. Firstly, they found that stylus shape had very little effect on the rate of wear of a stylus tip. You read that correctly. To quote the paper, “A comparison of styli with long contact tips and styli with biradial tips revealed no significant difference in the rate of wear between the two groups as a whole, although there were differences between individual tips.” Secondly,they found that tracking force (VTF) is a major factor in tip life, regardless of tip shape. Their results reveal a faster rate of wear as VTF increases, particularly above 1½ grams. For example, they determined that compared to double the VTF at 3 grams, a stylus tracking at 1½ grams would last 20% longer.

Based on this research, Shure recommended that at 500 hours, a stylus needed to be evaluated since it likely needed to be replaced. This equality of critical stylus life regardless of tip shape is counter-intuitive. But Shure’s research offered that it is due to the incredible variability in the groove on stereo records. These grooves undulate back and forth and up and down, in a groove that is also constantly changing its relative width based on the recorded music. The record groove exposes the stylus to continuously variable wear across portions of the tip. Furthermore, the stylus contact to the groove walls is longer with advanced tip shapes, therefore, the impact of wear abrasion from embedded dirt, including from diamond dust itself, is actually greater.

My Experience

Over the last six months, I’ve been conducting a blind A/B evaluation of two company’s RCA interconnects, two sets as installed between my phono preamp – linestage – amplifier. For the listening line, I use an Ortofon Cadenza Black MC phono cartridge mounted on Pete Riggle’s The Woody unipivot tonearm, on a modified JA Michell GyroDec SE turntable. The tracking force I use is 2.3 grams as recommended by Ortofon, and I dial-in a precise Baerwald alignment. Of the five reviewers involved in these interconnect evaluations, one is a musician and the only woman. Straightaway she noticed slight distortion in the woman’s voice on a folk record that was one of the four titles every reviewer listened to. For months, I had noticed a touch of introduced sibilance. One other reviewer noted that too. Since I can vary the stylus rake angle I fussed with it to no avail on limiting sibilance. I suspected something might not be perfect with the stylus, yet I kept using it.

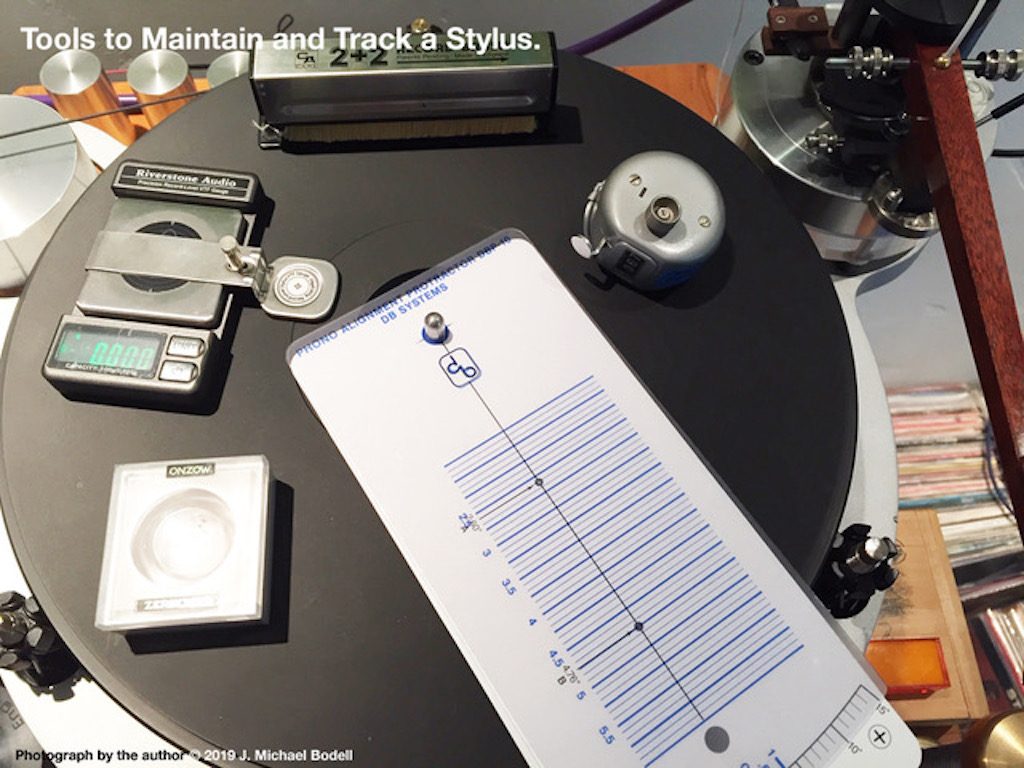

No vinyl record ever visits my turntable unless it is first cleaned and re-sleeved. I use a VPI17 vacuum machine with cleaning solutions from AIVS. More recently, I have been cleaning records in an 80kHz ultrasonic tank. Sometimes I use both machines to clean a record. Prior to any play, I clean the stylus with an Onzow ZeroDust cleaning pad. Religiously, I track every side of record play on this cartridge with a hand-held counter. For example, 1,500 sides of play is ~500 hours of use on the stylus. I was at 2,400± sides of play at that point, or ~800 hours. Another way to think about it, the diamond traveled a little over 700 miles in that many hours of record play on vinyl as clean as I can get it.

Due to my reviewer’s comments on distortion, I put the question of wear hours to a well-known U.S. dealer of Ortofon cartridges and manufacturer of vinyl cleaning solutions. He told me Ortofon advised that for a unipivot tonearm, 1,600 hours of play was tops, and for a gimbaled arm, 2,000 hours was the point to retip the stylus or replace the cartridge. Based on my reading, those benchmarks have become conventional wisdom for many vinylphiles.

At the same time, I emailed this same question to James Henriot of Whest Audio in the U.K., the designer and manufacturer of world-class phono preamps. I use a Whest phono preamp and acquired the cartridge through him. He told me that somewhere between 400 to 500 hours, the Shibata-tipped stylus was worn sufficient to create inner groove distortion, and at 700 hours, the worn stylus was capable of damaging vinyl (personal communication, e-mail). He told me the telltale early signs are sibilance and distortion on higher register voices, particularly in the inner grooves. I was surprised because I thought this stylus had another 800 hours of useful life.

People generally believe they know far more than they actually do, and as a consequence, they can be highly skeptical of new information. In my case, I had a hard time believing what Mr. Henriot was telling me, so I pressed him on it. He told me that JICO—a Japanese company—has studied this in great detail. JICO began manufacturing steel record needles in 1959 and modern diamond tipped styli in 1964. They examined in detail the wear on a diamond stylus at different hours of play and measured the resultant sonic impacts to come up with ~400 to 500 hours for stylus life on advanced tip shapes.

Henriot said stylus life is just a matter of frictional wear on a cut natural diamond against vinyl given the tracking force employed, quality of the diamond and the vinyl, and cleanliness of the record. Where the physics gets complicated is in advanced stylus shapes designed specifically to increase the surface area contact with the record groove. I knew diamond—the most common material used in modern day styli—has a rated hardness of 10 on the Mohs scale, the highest value for a mineral. Diamonds have a tetrahedral lattice crystal structure with one carbon atom linked to four other carbon atoms. The covalent bond structure forms a very strong 3-dimensional lattice, which is the reason for the extreme hardness of diamond. In diamond crystal structure, however, hardness is a vector property that varies with its three crystal faces and also with the direction on those faces. That hardness varies materially in a diamond is common knowledge to diamond cutters. From crystallography, the octahedron axis is the hardest. Therefore, a diamond stylus tip manufactured with great care along that axis produces the longest lasting stylus.

To say the least, I was stunned by this shortness of stylus life compared to conventional wisdom and marketing claims. The differences of opinion that I found in a web search were shocking. For anecdotal reporting by users who support the JICO research see the Steve Hoffman Forum, “JICO SAS Stylus”, the post by “rushed again” dated 10 June 2011: forums.stevehoffman.tv/threads/jico-sas-stylus.253426/. Also, see the thread “How Long Does A Stylus Last Before Replacement Is Needed?” started by “desktop” in March 2009 on the audio forum Vinyl Engine, www.vinylengine.com/turntable_forum/viewtopic.php?t=17853. Also on the Vinyl Engine see a 29 January 2011 thread “JICO Rates Stylus Wear” begun by “desktop”: www.vinylengine.com/turntable_forum/viewtopic.php?t=34521. The information gathered by poster “desktop” is superb. The bottom line: The clear-eyed view is a stylus regardless of its shape has a useful life of ~500 hours.

The table below shows conservative stylus life by stylus tip shape and a range of stated life from a multitude of sources. The “Hours of Play” column on the left is derived from research performed by Jico and presented by SoundSmith (see www.sound-smith.com/articles/stylus-shape-information). Apparently, according to JICO, the amount of playing time where a stylus will maintain its original specified level of distortion (~3.0%) at 15kHza is as follows:

Stylus Shape Hours of Playa Stated Life (hrs), Othersb

Spherical/Conical 150 300 – 800

Elliptical 250 500 – 1,000

Shibata/Line Contact 400 500 – 3,000

Micro-Ridge 500 ±4,000

a JICO research as published by SoundSmith (ibid.).

b Estimates from numerous audio forum and company webpages, all without technical support.

According to JICO, at 400 hours a Shibata-tipped stylus—as found on the Ortofon Cadenza Black—is worn to the point where distortion at 15kHz is out of spec relative to a new stylus. To put that into perspective, 8 hours a week of record playing is just over 400 cumulative hours per year. These results mirror research published earlier by Shure. In reference to a Micro Ridge stylus, SoundSmith adds that this is not to say that at 500 hours a SAS stylus is “worn out” but has reached the point where distortion at 15kHz surpasses the level specified by JICO for a new stylus, i.e., 3%. SoundSmith then states, “Some manufacturers have traditionally defined a stylus as being ‘worn out’ when it starts to damage the record…in these terms the figures provided by JICO can at least be doubled, and in some cases quadrupled.” The maximum lifeb shown above (right column) for various stylus shapes was gleaned from many sources and claims of higher hours of life were not accompanied by any published scientific studies. Other work presented herein cautions that once distortion is audible, whether we actually detect it or not, detrimental wear shortly follows. Needless to say, the confusion over ultimate stylus life continues.

JICO is rather straightforward. On JICO’s website pertaining to their precision-made premium quality, octahedron face-oriented diamond Super Analog Stylus (SAS) hybrid Micro Ridge cartridge, they state, “On average the stylus lasts two or three times longer (about 500 hours) than the average diamond tip stylus.” I read “lasts” as maximum life or near it, particularly since JICO qualifies that this “life” should take into consideration various playing conditions. What JICO recommends for various stylus shapes as published by SoundSmith is a salient guide for when to have a stylus checked. The question of stylus life regardless of its shape has become in my opinion a bit like asking “how long is a piece of string,” answered in riddles, and that makes this an important issue for vinylphiles as it pertains to the potential ‘risk’ of damaging valuable records with a worn out stylus. Unfortunately, an obvious and significant gap in verifiable knowledge persists, from the conservative analyses by JICO to the extremes of unsupported end of useful life, with no meaningful published data in between.

Steve Leung of Vinyl Audio Science (VAS) has been making and repairing phono cartridges for over a decade and has experience in almost every type of problem with a phono cartridge. For diamond stylus retipping Mr. Leung noted that the stylus may “work” technically for up to 2,000 hours and will still be on the cantilever, but the cartridge will not sound like when it was first broken in (personal communication, e-mail). From his experience, he sees two main takeaways: firstly, a stylus will last 500 to 700 hours and that will be the end of optimal play and good sound; and secondly, 2,000 hours represents the end of physical life of the stylus. Several manufacturers suggest replacing the cartridge or stylus by 2,000 hours.

When I finally recognized distortion on my Shibata–tipped cartridge, Mr. Henriot recommended in no uncertain terms Expert Stylus & Cartridge Co. in the U.K. to retip the Ortofon. He added that Expert makes diamond stylus tips that last a bit longer because the firm aligns the diamond tip along its strongest axis, just as JICO does for its SAS. Clearly, given the expense of today’s high-end cartridges with advanced stylus shapes, retipping with a high quality diamond is cost effective compared to acquiring a new cartridge. Based on his powerful recommendation, I sent Expert Stylus Company an email.

Expert Stylus Company is one of the world’s largest manufacturers of diamond styli. They supply replacement styli to the Library of Congress, for example. Expert currently produces over 100 profiles of diamond and sapphire styli for all types of phonograph systems. Expert also offers comprehensive stylus replacement service and cartridge repair for all types of phonograph cartridges. They have been doing this specialized service for over 25 years. The company’s laboratories are possibly the most advanced anywhere with facilities to manufacture precision components necessary to repair most makes of magnetic and moving coil cartridges. I arranged for them to examine my cartridge.

The Last Groove

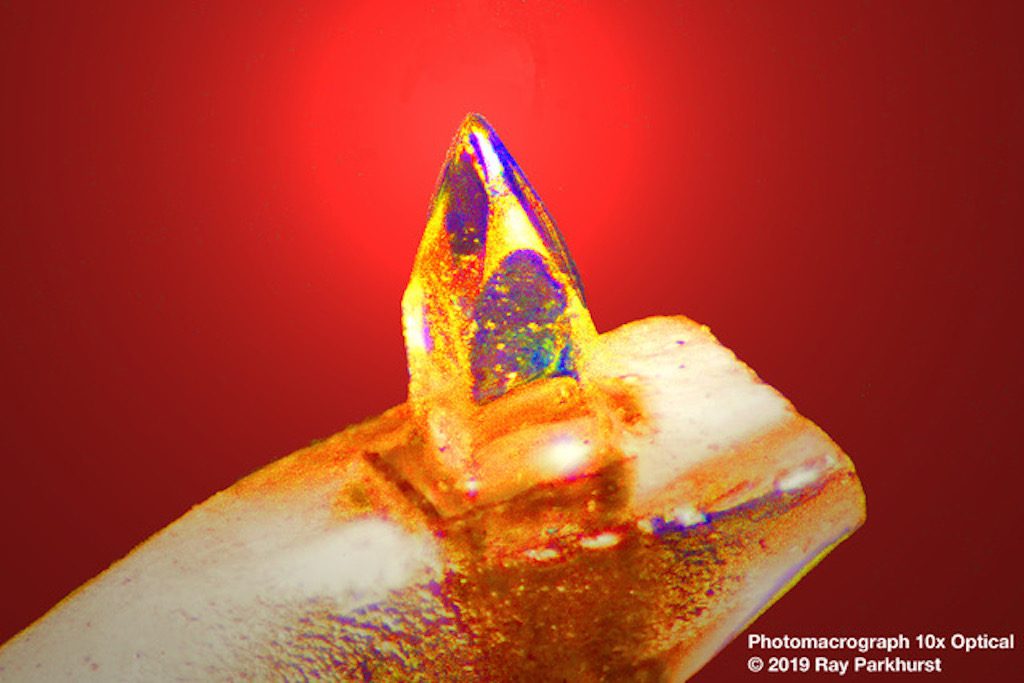

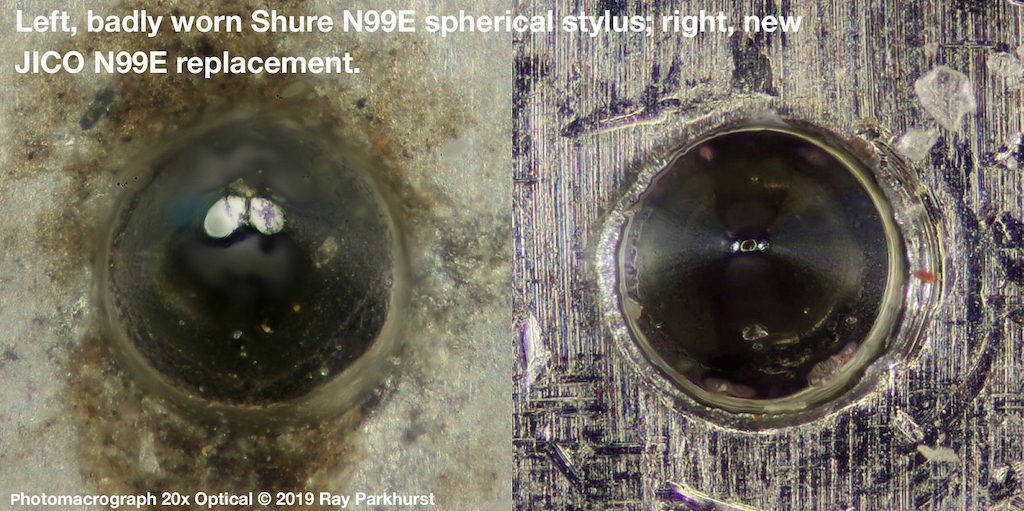

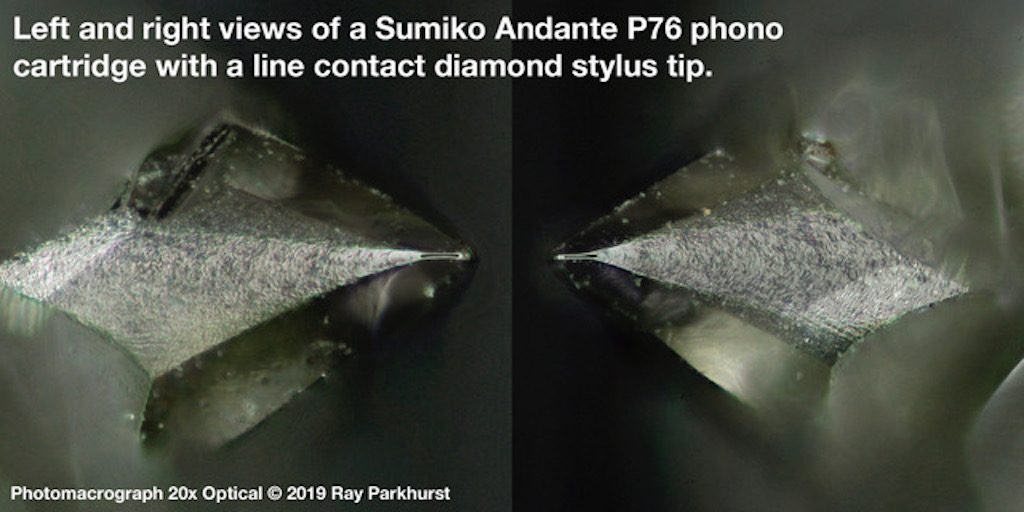

Here is my take. Regardless of its shape, as a stylus tip wears on the sides of a vinyl groove, it facets the diamond to create a worn edge or flat area on the sides of the tip. These so-called flats eventually represent critical wear as described in detail over 40 years ago by Weiler, Schwartz of CBS, and Shure Incorporated. Even for advanced stylus shapes as determined by JICO, these flats are seen clearly as “cat’s eyes” in images by Wayne Grundy in his excellent “how to” article, “Using Macro Photography to Check Stylus Wear,” published on 24 December 2018 on the Lossless Sound website, available here: losslesssound.wordpress.com/2018/12/24/using-macro-photography-to-check-stylus-wear/.

Stylus wear can be seen on a cleaned stylus using a 200x USB/digital microscope; a decent one can be purchased for $250 or less, but the real acid test for critical wear continues to be careful listening for playback distortion and keeping track of total sides played. If you can afford it, having beforehand a replacement cartridge or stylus provides an opportunity for microscopic comparison of a new stylus with the worn one. With photomicrography, one can only really tell if a tip is worn out with repeated periodic imaging for comparative analysis. Alternatively, companies that retip offer evaluation services, along with a few remaining brick & mortar shops in larger metropolitan areas. For superb instructions on procedures and required equipment see the Vinyl Engine audio forum thread “Stylus Evaluation Imaging” begun by Ray Parkhurst, under Board index, Hardware, Cartridges and Preamps: www.vinylengine.com/turntable_forum/viewtopic.php?t=92996.

Be prepared for hard work when you first begin evaluating stylus wear. James Henriot of Whest offers, “Most (99.9%) ‘audiophiles’ have no idea of what the Shibata line contact profile looks like, so to put a worn one under a 200x microscope is like asking your ‘average Joe’ to remove your kidney with precision.” He notes that the wear pattern is visible ‘face on’ (i.e., front-on) yet virtually all stylus tip images published in audio magazines are taken ‘side on’. Henriot elaborates that to appreciate wear on a modern stylus you must know the original tip profile and be able to measure any wear properly against a known reference image. The best way he suggests is to superimpose images of the worn profile against a new profile, precisely as illustrated in Ray Parkhurst’s image of the N99E tip. For these comparative images, Mr. Parkhurst combined focus stacking with a lighting technique similar to the Shure SEK-2 microscope. Comparative images from a microscope or having a stylus checked by an expert will get that done. As Henriot adds, “We are talking about 10 microns wearing down to ‘what’?” That question of ‘what’ Henriot asserts is something only Expert Stylus, diamond tip manufacturers such as JICO, and a few other real insiders know with precision.

I learned along this sojourn that I was not alone in the confusion over the useful life of a stylus or in how to proceed next time around. For a supporting reference that says it all really without the additional material in this article see this 10 August 2012 post on the Steve Hoffman Forum under “What are the symptoms of a failing phono cartridge?”: forums.stevehoffman.tv/threads/what-are-the-symptoms-of-a-failing-phono-cartridge.174323/#post-7970798. Poster “5-String” writes,

“Concerning the stylus lifespan…here is an interesting story from my experience. Everywhere on the internet you read numbers from 800 to 1200 hours or even more before the stylus gets damaged and needs replacement. Not always true.”

“I used to have an Ortofon 2M Black, the one with the Shibata stylus. Every record I played was cleaned with the VPI. At approximately 650 hours of playing time, I took it to my audio dealer to examine it with the microscope. It needed replacement. I verified this with my own eyes, which was actually a fun experience and a great lesson to stylus geometry.”

“Were there any symptoms, like sound degradation, distortion, etc. before I took it to the microscope? Nope, not that I could tell. So here is my advice.”

“Examine your stylus with a microscope. That’s the only way to tell and to be absolute sure about the condition of your stylus.”

As for the diamond Shibata stylus on my Ortofon Cadenza Black with 800 hours of play on very clean records, the report I received from Expert Stylus stated that its tip was “badly worn” and clearly the cartridge needed to be retipped. My thinking now is that at some point between 400 to 600 hours or 1,200 to 1,800 play sides this advanced diamond stylus regardless of its tip shape would be worn sufficiently to begin high-frequency distortion, depending also on VTF, quality of the diamond, and condition of the vinyl records being played. At 650 to 700 hours the worn diamond tip may begin to wear record grooves at an accelerated rate, and for that reason, a good rule of thumb that I will adopt is to check this type of stylus by at least 500 hours of use, and retip it if necessary. JICO pretty much nailed it on hours for the various stylus tip shapes.

“In an age of increasing sophistication in technical measurements and during this renaissance in vinyl sales, phonograph cartridge manufacturers need to provide users with pertinent information on critical stylus wear and useful life supported by detailed scientific research.”

Keeping track of the number of listening hours or sides of play is important support, and easily done with a hand-held counter. Consider also the effects of VTF on the stylus where higher VTF may cause faster wear and too low a VTF causes permanent damage through mistracking. A properly aligned cartridge using a protractor avoids differential wear. Maintaining clean records with a vacuum or ultrasonic record cleaning machine not only minimizes record wear but also extends stylus life by reducing friction-based abrasion.

Bottom line, based on the sum of my investigations, advanced diamond stylus life is estimated to be near 500 hours, and probably much lower for spherical and elliptical tip shapes as noted by JICO. Play above 800 hours risks progressive and permanent damage to vinyl records, so it is critical to get an advanced stylus tip examined at near 500 hours of use, much sooner for a spherical or elliptical tip. With proper care and careful examination, you will learn for yourself how long a stylus will last.

Debate may rage on whether or not the diamond tip shape makes any difference in the play hours prior to the point of critical wear. Shure, JICO and Ortofon have performed this analysis, but for the most part the data has not been published, not as it was in 1954 with Harold Weiler’s detailed research. Yet based on my experience with the line contact Shibata tip and what I have learned from the experts in my research, it may not matter. I now know a lot more about stylus life. The question on critical wear is simple; we need to see the data.

If this paper convinces vinyl lovers to be more mindful of good maintenance on the part of their audio system that is subjected to the most wear—the stylus tip on a phono cartridge—it will have accomplished my primary objective. None of us want to play our records on a critically worn stylus that risks permanent groove damage to our favorite records. This article deals with how and why that record damage happens leading directly back to an overused and worn out stylus. In this sojourn I examined sales materials and user manuals for many dozens of cartridges offered by most major cartridge manufacturers. The frontend information is fantastic, listing from 12 to 19 technical parameters of their offerings. Yet finding information about useful stylus life was rarely among those details and typically difficult to find. And that in my humble opinion presents to cartridge and stylus tip manufacturers—other than Shure, JICO and Expert—a prime opportunity to set the record straight. In an age of increasing sophistication in technical measurements and during this renaissance in vinyl sales, phonograph cartridge manufacturers need to provide users with pertinent information on critical stylus wear and useful life supported by detailed scientific research. Harold Weiler 65 years ago pioneered a way to convey precisely that needed information.

© 2019 J. Michael Bodell

Acknowledgements

I owe a massive debt of gratitude to a lot of folks. I would like to thank all the folks who before me encountered similar issues and posted their experiences and concerns on audio forums. I read thousands of those posts and quoted Chris Kost (with his permission) for this article. I am in awe of Harold Weiler who approached the subject of stylus and record wear in the absolutely correct manner in the early 1950s, in work that as far as I can tell has not been replicated and made public. It should be. This article emerged as I stitched and cobbled together parts of my discovery; a lot of folks in my network offered suggestions, edited grammar, added essential information, showed me other resources, and simply encouraged me to keep looking. Thank you all. Ray Parkhurst provided images for this article, and as I discovered later, he had a keen eye for detail as an editor. He made this paper much better and for that I am grateful. Bill Hart was instrumental in getting me to write this paper when I shared with him early on what I had learned about stylus wear. He guided me through a few important traps along the way. James Henriot who designs and manufactures very fine phono preamplifiers needs a call out for his direction, which proved crucial in my research. Also, I acknowledge the help of Jeffrey Sorensen, Fred Linthicum, Pete Riggle and Matt Spangler, who read and in some cases re-read the text to help me smooth out the rough patches. Lastly, I want to thank a host of earlier researchers who over the last 60 plus years shed light on the subject of critical stylus wear. All of them have a voice in this article, including those folks who more recently shared essential insights but did not want to go on record. I thank them all, for they moved the text in a needed direction.

Great and very informative article, thanks…

Thank you for taking the time to collect this information and posting it here. I’ll be referring back to this for years to come.

As a broadcast engineer starting (professionally) in 1970, I’ve probably worn-out more diamonds that most people here. Back in those days, just about all small and medium sized market stations played all their music from vinyl (and styrene) records. Top-40 stations mostly 45’s, and album oriented stations from LP’s.

All during the 1970’s the most common broadcast phono cartridge in just about any radio station was the Stanton 500A…A conical .7 mil magnetic. Typical VTF was determined by a combination of trying to keep tracking distortion tolerable, and minimizing record wear. Wear especially to the critical lead-in grooves, because they got double or triple, or more play time compared to the rest of the disk. Cue-burn, especially on styrene 45s was a real problem! And a station may only get one copy of a hot single.

We found that 2.2 grams was the best compromise for the 500A cartridge. At that VTF, even styrene 45’s could usually stand up to several months of getting played (and cued) 4 to 8 times a day without sustaining cue-burn to the lead-in grooves.

Stylus wear was critical to keeping the records sounding good on the air. Not only from record wear, but in terms of how the stylus sounded. What we found was that the .7 mil diamond in the 500A cartridges would begin to sound like it was done-for after about 500 hours of play…unless it was damaged by a ham-fisted DJ sooner.

Interestingly, record wear was usually NOT increasing at that point…But it was clear that the sound quality had degraded by that time. High frequency response would be clearly starting to roll-off, and HF distortion would be starting to increase. An increase in cue-burn of the lead-in grooves would soon follow if the stylus wasn’t replaced pronto.

For 24 hour stations that usually meant changing the styli in both on-air studio turntables every 2 months, and for daytime only stations about every 3 months. It’s a good thing that Stanton only charged about $6-$8 each for replacements! An AM/FM combo would go through about 24 new styli / year.

Of interest is that the new styli needed a “polish run-in” in the production studio for a few hours before installation in the air studio…or else the new styli would quickly cause cue-burn on styrene 45s. I’d use a locked-groove at the end of an LP for this, running at 45 RPM for a few hours. This resulted in much less cue-burn to styrene 45’s from newly replaced styli.

do