Rock music has always been dangerous; its precursors, from secular black music and the blues in the decades before WWII, to rockabilly and rock and roll of the 1950’s- music that spoke to the travails of the world, of carnality, crime and pain, and all those indecent thoughts and pleasures of life- posed an obvious threat to social conventions.

It wasn’t just a battle between the sacred and profane; it was the fear that the sex, drugs, politics and other uncomfortable subjects would influence and seduce the young. That fear is certainly nothing new- it can be traced to the dawn of recorded music- “race records” didn’t “cross-over”; even among black performers there was a separation between more acceptable forms of “church” music (gospel) and the dirty blues.[1] Elvis Presley represented the same threat, as did punk, metal and “rap” in later decades.

But when the Beatles got all mystical, and indulged in mind-expanding substances, it was as pacific as a suburban yoga class. The Stones were the anti-Beatles, whose early drug busts, founding member’s death and sexually charged performances represented a much darker side. That image was reinforced by the events at Altamont, where an increasingly restive crowd, a group of Hell’s Angels and the violence surrounding the stage are now firmly cemented into pop culture as the death of the “Woodstock Nation.” So much has been written about these subjects there seems little worth adding.

I was reluctant to read a book about the early days of the Stones for other reasons- I had little interest in the salacious aspects of their lives and even less interest in celebrity name-checking. In fact, I don’t even consider myself much of a Rolling Stones fan.

But, if I had to pick a single song that represented the best of that band’s work, and perhaps late 60’s at large, it would probably be “Gimme Shelter” (the song, not the film), which still conveys a sense of danger more than four decades later. (Merry Clayton’s vocal part still gives me goosebumps). It is a glorious piece of music even if it doesn’t conjure up memories, real or imagined.

A recent online discussion about the violence of the Altamont show led me, not to the Gimme Shelter film (whose surviving maker, Albert Maysles, died just a few weeks ago), but to Stanley’s Booth’s book: “Dance with the Devil: The Rolling Stones and Their Times” (1984), republished as “The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones” in 2000.

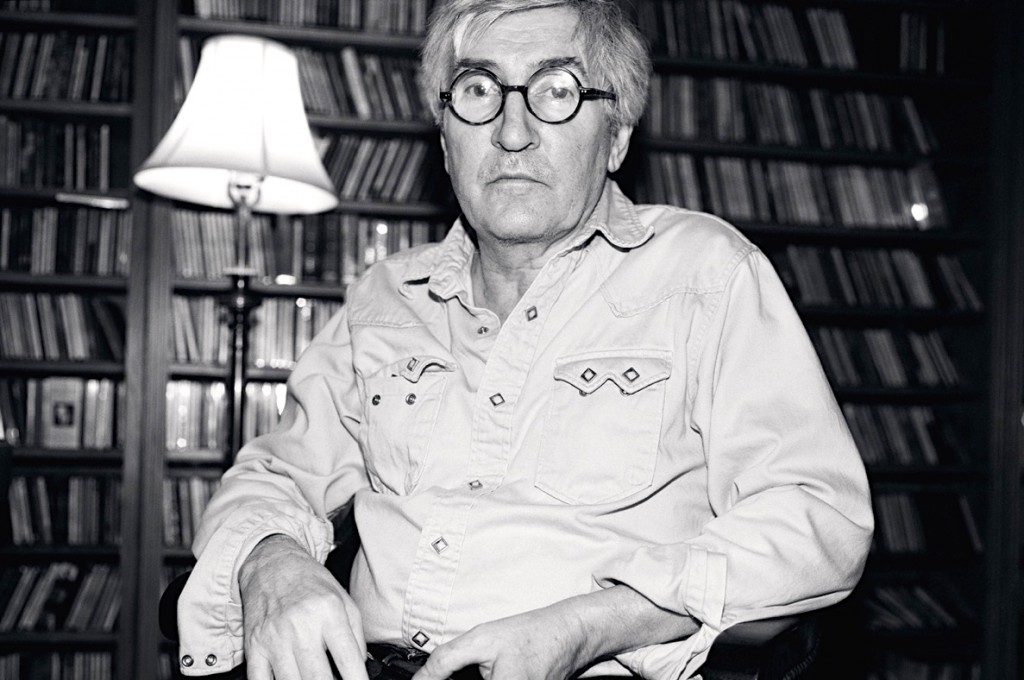

Stanley Booth grew up in Georgia, wrestled at least one alligator in his youth, went to college and along the way, befriended at least one old time blues musician. Furry Lewis, who had played with W.C. Handy’s Orchestra and recorded for Vocalion in the 1920’s, was sweeping streets in Memphis when Booth first met him. Booth wrote about Furry in a piece published by Playboy magazine in 1970. It took Booth almost fifteen more years to write about his early days on the road with the Rolling Stones. It was this book that set me on the trail of Stanley Booth.

How Booth got access to the Stones is part of the story, but not the most interesting part. Nor was the seemingly carefree way he became part of the entourage; sharing the drugs, the limousines, and the hotel suites. These were not the days of “media handlers” and cultivated public images- the portrait Booth paints –of bleak rooms, bad food and a nightmarish series of zig-zag charter flights across the U.S.—made “rock star” seem like a bad career choice, if not an exhausting one. It took Booth a long time to write his book. And when it was published, it apparently attracted little notice in the States (though it did well in the UK). If that’s all there was, you wouldn’t be reading this now. But Booth gives us a fresh look at what the early days of rock music business looked like in action, from the inside, without the filters of public relations, lawyerly editing or the layers of corporate bureaucracy.

The quality of the writing itself is stunning- Booth has a miserly grip on words with a telegraphic style reminiscent of a good noir. But what is more striking is the easy, offhand camaraderie among the group members, their entourage and the author—a quality that is almost impossible to imagine today, in biographies that burnish images and airbrush warts.

The band, already famous, didn’t seem in awe of their own stardom, perhaps because they were struggling- with their management, their label and their overall direction. Their early success had started to falter, and previous U.S. tours, at gyms, colleges and rank venues did not portend a career in ascension. By the time the band embarked on their 1969 tour, Brian Jones was in his grave, the Stones’ attempt at psychedelia – in the form of Their Satanic Majesties Request -had received a lukewarm reception, publicly and critically. The follow up, Beggars Banquet, was much better received (including the classic “Sympathy for the Devil” as well as “Street Fighting Man”) and formed part of the set-list for their 1969 tour and many others that followed. But, along with their other troubles, the band needed money to support the tour, which depended on advances from the shows. The Maysles brothers, who filmed the Madison Square Garden concert, also signed on to chronicle the events leading up to Altamont.

At the time Booth jumped on the Stones’ bandwagon, Brian Jones was already dead, but like a character in a Shakespearean play, his figure still looms. (Booth does try to root out some truths about Jones, but those seem elusive). Instead, the most powerful parts of the book seem to occur with unstudied nonchalance: Booth is Forrest Gump in some ways; he is there when Jimi Hendrix stops in to say hello (but declines the offer to tune up and play); he is backstage at the Garden, where Janis Joplin joins a young, beautiful Tina Turner on stage (Ike, who was part of the tour, just keeps putting out some seriously evil vibes). B.B. King, young and vigorous, plays the blues to receptive audiences, and Chuck Berry always makes sure he is paid before he gets on stage. Even a youthful Terry Reid is part of the line-up. (Reid is another talent who deserves more attention today, but more about that later).

The casual, almost offhand relationship among these performers and members of the public is inconceivable today, where few things in the entertainment business seem unplanned or un-“managed.” Nothing stopped the Stones and their friends from wandering the New York streets in search of a meal late one night after a show. The description of the place rings true- the food was just as bad years later when I ate there.

Though Booth’s book is often cited as a fair recounting of Altamont and its aftermath this is, in some ways, the least interesting part of the story. Although Altamont is almost reflexively cited as the “end of an era,” the reality was quite different. It was a violent decade- the Vietnam War, the protests, the assassinations, the various radical movements, the Tate-LaBianca murders, just to recount the obvious, were already prologue. To read Booth, you get a sense, not just of the shock the band felt afterwards as they beat a hasty retreat from the stage; more profoundly, Jagger seems to realizes that he was ultimately unimportant in the midst of an event at which he was supposed to be the center; the violence continued and peaked in the face of his pleas.

I don’t know what effect this had on the band’s psyche or their music. I do know that the music that made up the Stone’s set, part Beggars Banquet, a taste of Let it Bleed, was then followed by Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main St. These albums, as a whole, are generally considered to be the strongest albums the group made. (Finding good sounding pressings will be the subject of a separate piece).

I tracked Stanley Booth down in Memphis and asked him for his thoughts about those days, from the vantage point of now more than forty years:

SB: There’s no way my book could have been written any later than it was.

Rock and Roll had become so micro-managed and corporatized; we were just a bunch of blues lovers out to see the world. And by the time my book about the Stones was published, America was a very different place. The book had no impact in the States at the time it was first published, even though it was well-received in England.

You are reputed to have been with Otis Redding when he wrote “Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay.” Can you tell us about that?

SB: In December of 1967, on assignment from the Saturday Evening Post to write a piece about the Memphis Soul Sound, I was at 926 East McLemore in Memphis, the Stax recording studio. After a conversation with the drummer Al Jackson, I stepped out onto the sidewalk under the marquee (Stax had originally been a movie theatre) to write in my pocket notebook, so as not to forget Al’s wise words. As I stood there, a white Lincoln Continental limousine parked at the curb. A large young black man emerged from the back seat. It was Otis Redding. I introduced myself and we went inside, down to the recording area and sat down on folding chairs. We were soon joined by the guitarist Steve Cropper, and I sat facing them, watching, listening and writing as they wrote “Dock of the Bay.” I spent the last week of Otis’ life with him, told him goodbye on Friday, and Sunday night he was dead. He made other people feel good. I’ve never really recovered from his death. [2]

You’ve written about a variety of different musicians- from the old bluesmen to Gram Parsons. Was this happenstance, a reflection of the music you personally loved and if so, what’s the common thread?

SB: If I had to put the thread in a word, it would be redemption, something we all need. We’re all sinners – but equally (at least potentially) saints and prophets. The great blues masters (and I would include Gram Parsons in this pantheon) knew that music has the power to transform poverty, pain, and suffering into something transcendent.

Do you have any projects in mind? I know I asked you about an autobiography or a film. I think a lot of people are fascinated by the era you chronicled and all of the people you knew and worked with.

SB: I’m just now finishing two books: Where the People Smile, a collection of writings about Memphis and Memphians, and Blues Dues, which consists of essays and stories about non-Memphis blues people. I’m also working on some other books: A Tree Full of Owls, about insanity in my family; Alligator Alibis, about growing up in the pine woods by the Okefenokee Swamp –- by the bye, I never wrestled an alligator – I did when I was about twelve shoot one dead with my Remington Targetmaster –and The Pea Patch Murders, about a case my farmer great-uncle Henry Mullis solved in South Georgia in 1931. I’m also writing a book I intend to leave to the Catholic Church, which has freed me from being an animal. After these are done, we’ll see. There are some other things in the trunk.

Stanley Booth’s bibliography is extensive and his writing deserves fresh attention. “The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones” is a worthwhile read, whether you lived through the era or not. Some of his other works are listed below. * I’m waiting for The True Adventures of Stanley Booth. That would be a hell of a read.

*SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones

Rythm Oil: A Journey Through the Music of the American South

Keith: Till I Roll Over Dead

Booth maintains two websites: stanleybooth.com and grey-ghosts-press.com. The Grey-Ghosts site is particularly cool and I recommend you take a look; it has some great photography, including pictures taken by Booth, offers his books and more of his story.

____________________________________________________________________

[1] This is a subject worthy of scholarship far deeper than mine; while some acts were mainstream or accessible to broader audiences in the day, including jazz and some folk music, much of the early Delta blues remained obscure after the Depression. Its re-discovery in the 60’s (beyond the scholars and documentarians) as a living art form was due in part to the deep affection of the UK bands (and US blues aficionados). Some just tapped this vein for their own “take” on the material, but others sought out the original artists, living or dead, to bring them to the attention of new generations. The Stones were influenced by this as well. Newer bands, like The Black Keys and Jack White’s work, including his Paramount boxes, are just the latest examples.

[2] I asked Booth about this, because he had only met Redding at these sessions: “We grew up in the same town, and both went to high school in Macon, but due to segregation, it wasn’t the same place for us. Yet, I always felt welcomed in black neighborhoods, churches (where the best music was) and something just clicked with Otis Redding- he affected me. We said good-by on Friday and on Sunday, I learned he was dead.”