Vertigo Records, in the era of the ‘Vertigo Swirl,’ is legendary- from its unique ‘swirl’ label, to its eclectic mix of artists, strong musical talent and extremely high production values, to the ‘art’ of the album jackets and the clever album packaging. My introduction to the label came late-this UK label carried the work of some famed artists, like Black Sabbath, but so many of its records- and some of the most desirable ones in my estimation, musically, were recorded by bands like Cressida, May Blitz, Patto, Affinity and Gracious, which are hardly household names. Even fewer of these bands and records made a dent in the U.S. market.

Today, these records stand out as almost monumental musical achievements- listen to the way Cressida combines an almost classical music formalism with pop “hooks”, or the sublime jazz as progressive rock anthems of Colosseum’s first album on Vertigo. Or the biting psychedelic guitar work of May Blitz’s “I Don’t Know” (from the first, self-titled album) powered by the drumming of Tony Newman (who went on to drum for Jeff Beck).

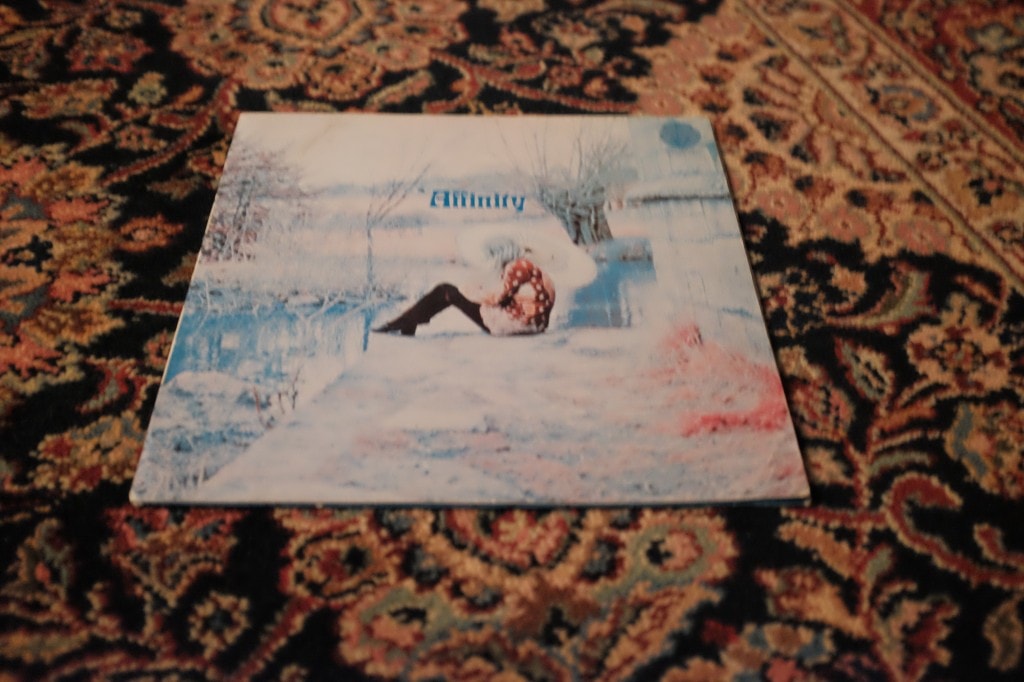

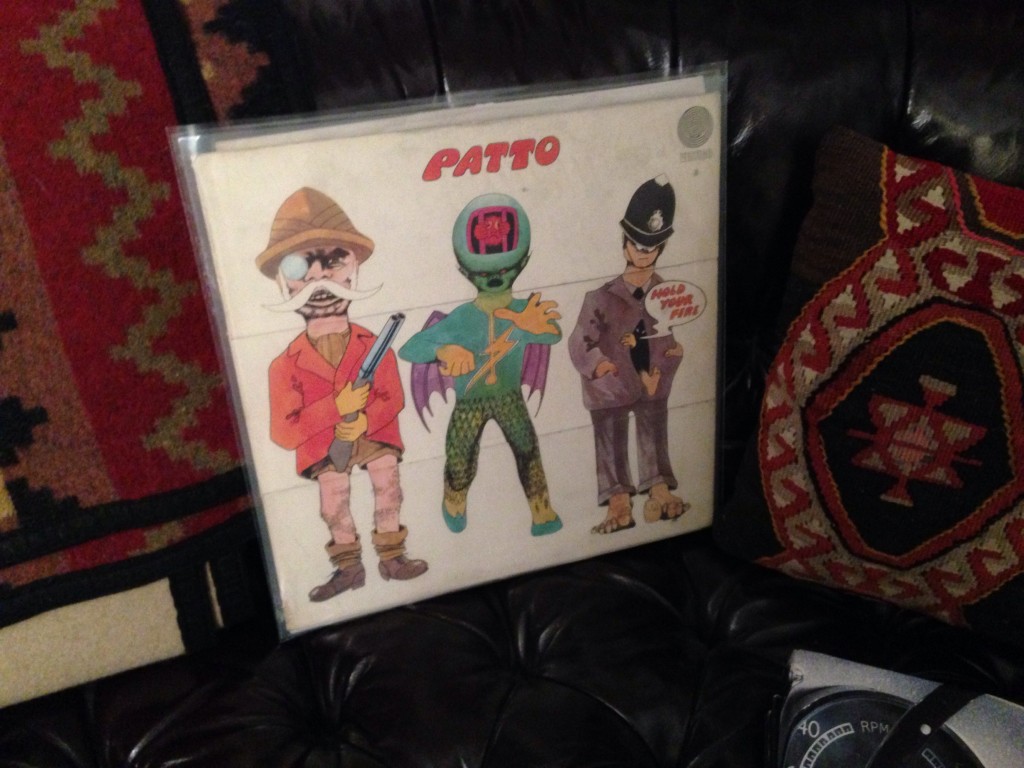

Many of these records are now sought after by well-heeled collectors, but what drew me in was the music. As I selectively acquired some of these old UK pressings, I grew more impressed- the production values were extremely high- the records sounded fabulous more than 40 years after their manufacture- and among the many Swirls I now own is a range of different musical styles that has no real counterpart today. Jazz mixed with raw psychedelic rock (Affinity, another killer Vertigo Swirl) sat comfortably with the early underpinnings of “heavy metal” (Black Sabbath), or the soulful psych-inflected renderings of Patto, whose guitarist, Ollie Halsall, played guitar with a vibraphonist’s touch and sensibility. My sense of wonder–having been in and around the business side of the music business as a lawyer for decades, “wonder” is a scarce commodity–led me to try and find out more about the history of the label and why these records were (and today remain) so special, musically, sonically and artistically.

The Vertigoswirl.com website helped- it is a fairly comprehensive listing of the releases during the ‘Swirl’ era of Vertigo, and contains label information, credits and even matrix information for the UK releases and many of the Vertigo releases in other countries.[1] But even that site offers only an overview of the history of the label and its origins. Gerry Bron, who co-produced the first Vertigo Swirl album (Colosseum), as well as a host of other bands, including Uriah Heep (which also appeared on Vertigo) and had his own label, Bronze Records, is often credited as a co-founder of Vertigo, along with Tony Reeves, who played bass guitar with Colosseum and co-produced that first Colosseum album, among others. I couldn’t reach Bron, who passed away in 2012. Tony Reeves responded quickly to my inquiries, and just as quickly disclaimed any role as a founder of the label. Reeves pointed me to Olav Wyper, who is often referred to as the man at Philips responsible for the Vertigo label.

After having been at EMI when the Beatles ran the place, then with CBS at the beginning of its switch from soft pop to rock, and later (after Vertigo), at RCA UK to work with artists like David Bowie, you get the impression from Olav Wyper that he has already given more than his share of interviews. When I explained what drove me to seek him out- that I was captivated by the music and sonic quality of the Vertigo Swirls, and had many unanswered questions about how this coalescence of music, engineering and art came together, Mr. Wyper opened up:

OW: I was at CBS at the time, and had gone to a meeting in the States to hear the latest roster of records slated for release. I was stunned by this material; it was new and fresh and different from the material then on the label. Blood, Sweat and Tears; Laura Nyro, Simon and Garfunkel, Spirit and Janis Joplin, among others. The albums should have sold easily in the UK but nothing happened. So, I took a step that was, it turned out, the first of its kind in the UK. We did a “sampler” called The Rock Machine Turns You On[2] that got everybody’s attention in the UK. Later compilations, using The Rock Machine “brand” and sampler approach, were used to introduce new artists and served as a vehicle to gain new audiences through a combination of good A&R, effective marketing and discounted prices that attracted new listeners. By this time, CBS was seen as the label of more progressive music.

I was then being “headhunted” by another record company. The headhunter did not want to disclose who he was working for at first, and when I pressed him (because I wasn’t necessarily looking), he said “Philips.” I couldn’t really take that seriously because Philips had virtually no presence in the rock/folk market and was a giant conglomerate known more for household goods and appliances than contemporary music. (Ed. Note: Philips’ classical label was another story but Wyper was being recruited to help Philips establish a presence in the rock/progressive market. Wyper did, however, have responsibility for classical and other genres under the Philips umbrella as well).

According to Wyper, he got on a private jet to Eindhoven, the Netherlands, where Philips was based, and negotiated a deal that put him in charge of a new label, with full control- A&R, hiring and firing, marketing, art direction-virtually everything. Wyper did the deal.

At the time, one of the acts signed to Philips was David Bowie, whose Space Oddity single was already in release, but was a complete flop. Wyper focused the company on this record when he arrived and the single charted at near the top in UK.

Wyper sat his team down to start with a fresh slate- musically, aesthetically, and focused on the market that was now blossoming for this “new” music. One aspect, often neglected, was the label itself:

OW: I wanted something that was very visual. You have this large space on a twelve-inch record that really doesn’t do anything. I have always been a very visual person- when I worked in advertising that was one of my strengths. And I wanted the label in the center of the album to be very visual. One thought I had- make it spell something only after the record is turning at speed-was something we tried to do without success.

I was sitting in traffic, it was raining; my car windows were steamy and I wanted to look at something in shop window across the street. I drew an increasingly large circle, like a spiral, in the fog of the auto glass. That was the starting point for “swirl” label that we developed with the input of our in-house art team, Linda Glover and Mike Stanford- the whole point was to draw you in, and combined with the label name I conceived- “Vertigo”- it captured the sense I wanted to create- a sort of hypnotic quality. It was also visually a lot more interesting than bare typeface of the standard label logo and copy on virtually every other record. I wanted this to function as “art,” and couldn’t have done it without Linda and Mike.

Ed.Note: The ‘swirl’ motif not only carried over to the logo on the jackets and elsewhere, but also to the inner sleeves, which are themselves collectible and an essential part of buying the old records, at least the UK pressings. Some of the Vertigo Swirls manufactured outside of the UK did not have these ‘swirl’ inners.

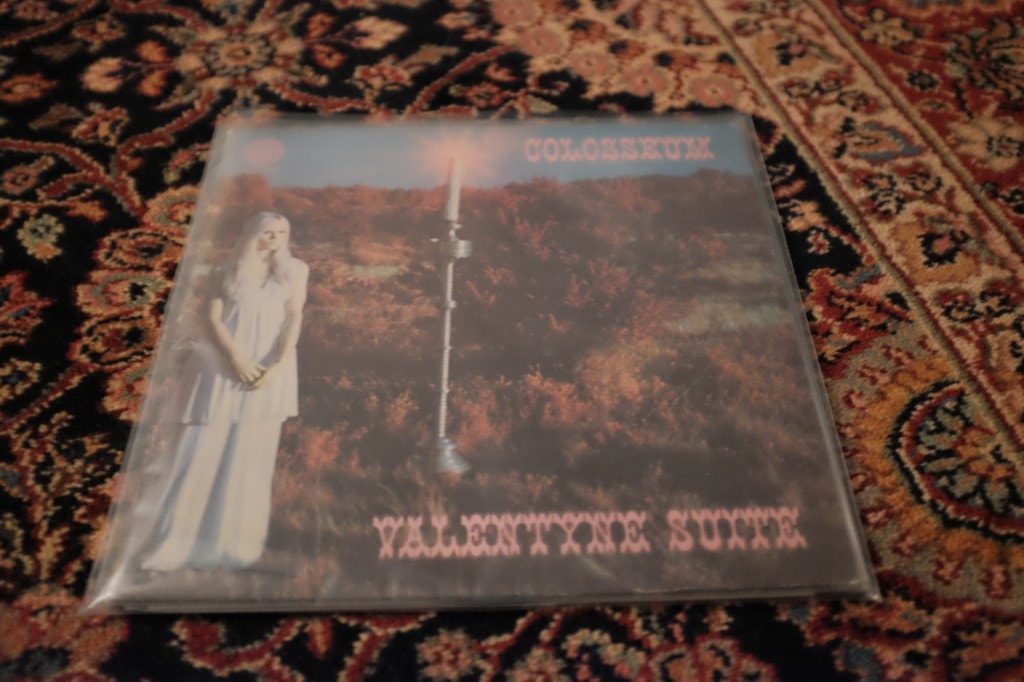

The first album release on Vertigo Swirl in the UK was Colosseum-Valentyne Suite. Colosseum, the band, had already been signed to Philips when Wyper arrived, but Wyper’s decision to make theirs the first album on this new label appears to be what brought both Tony Reeves and Gerry Bron into the Vertigo fold. It is a great album that stands up very well more than 4 decades after its release. It also had all the earmarks of the best of the Vertigo Swirls to follow: inventive, fresh music, played by real talent, mixing genres- jazz, rock, and what would eventually become known as a form of music labeled “progressive” (which, in my estimation, is an after the fact catch-all for something that is genre-defying). There is, of course, a psychedelic tinge to many of these records, but it sounds fresh and challenging, as it must have been at the time.

One of the other aspects of these records is a stunning clarity and vividness in the production, which led to an interesting series of observations by Wyper. I prompted this by suggesting that the production values of this era were a sort of “sweet spot”: the gear was a little more advanced than in the early sixties, but it was still not the heavily processed, huge multi-tracking stuff that came into play in the seventies as the “technology” improved in the studio.

OW: The reason these records sound good is because these bands didn’t need to do much overdubbing. They could all play in the studio as they played “live.” So that’s the reason it sounds less processed and more lifelike. One of the criteria my joint heads of A&R (Mike Everett and Dick Leahy) and I had for signing bands was they had to be able to play their music live. We used top producers. When we mixed, we weren’t using as much compression, and we relied on fewer studio outboard devices –they simply didn’t exist and what was available was pretty basic. The instruments were properly miked and separated by movable baffles; the drums were always recorded in a booth. We oversaw mastering at Philips for the UK releases. The mastering was done in-house at Philips for the UK releases but in other territories, if there were any volume in sales, the records would be re-mastered and pressed locally. Some of the sonic differences in mastering related to the equipment but also related to the sensibility of the particular mastering engineer.

The mastering can make or break a record. There is a huge sonic difference between the original UK Vertigo releases of the early Sabbath albums and their counterparts in the States (Sabbath was not on Vertigo in the United States). So, too, there were sonic differences among contemporaneous pressings of the same Vertigo album on the Vertigo label in other countries, which often favored the UK pressing.

One of the other reasons why some of these early UK Vertigo Swirls now go for big money is that, in some cases, there simply aren’t that many copies. It seems that, in many instances, it is the records that did not sell well, and were not pressed in substantial quantities that now seem to fetch some of the biggest prices. Sometimes, this is a little inexplicable, at least in hindsight. That first Cressida album is as good as it gets- those guys were entitled to the crown of ultimate “progressive’ bands as much as King Crimson, but unless you are into Vertigos or deeply into progressive music from the era, my bet is you never heard of the band. And a first UK Vertigo Swirl pressing of that Cressida album is big money.

Other records, like Dr. Strangely Strange’s “Heavy Petting”- well, I could understand why that didn’t sell, even if a very young Gary Moore is cranking out electric blues licks on this disc. However, that record today also sells for big money.

I tried to get a sense of how well these records did in the market at the time and roughly how many were actually made:

OW: Of the first 17 records on Vertigo, 7 charted in the UK and were significant sellers- the Sabbath records were huge sellers, even outside the UK; but our yardstick was 1,500 copies- and we made a profit at that point. Right from the outset, we did much, as a team, to give Philips a new credibility for rock and progressive music. As a matter of marketing, we wanted to sell the public on recognition of the label as a source for good music and aimed to release the Vertigo albums in batches- people thus looked for “what was new” on Vertigo. This meant that we released a lot of albums in a fairly short time. The better-known artists would obviously help sell other new or unknown artists by their association with the label. So, we had great bands; we recorded them well, using top producers. But, we also deserve credit for good marketing; remember, we were music people running a record business and recognized that we had to do a good job to serve the business side as well as the artistic side. By focusing on the strength and recognition of the Vertigo “brand”- from the swirl logo to the gatefold covers and the strong identity of the swirl design on the label of the record itself, all of this helped us gain recognition in the eyes of the public and ultimately, led to more sales. This also helped with the credibility of the label in the industry itself. We were attracting artists precisely because it was apparent that we knew what we were doing and were able to put together talent, packaging and promotion in a very effective way.

The London music scene of the 60’s has achieved a mythic quality. I suspect that some of it was probably pretty raw and unpolished without the help of a good production team. If Wyper was ultimately responsible for the musical choices at Vertigo, what was it that he was hearing, especially in light of the extreme differences in the kinds of music that appeared on the label?

OW: The bands needed good producers- live, a long song would work, but on an album, the songs had to be cut down. Good producers, who were also usually musicians themselves, also helped with arranging, or simply suggesting that the song be played in a different key. That all made a big difference when it came to recording bands, even those who were great on stage.

I asked Wyper to tell me what the industry and public’s reaction was to Vertigo once it got underway:

OW: The reception was fantastic- we were inundated with managers and bands who wanted to sign with us- they immediately recognized what we were doing, and how much ingenuity and creativity we were putting behind the label, which attracted the artists. We also spent a considerable amount of money on promotion- and we supplied tour support, which took advantage of an established market of fans that would be record buyers for these bands. Philips, of course, had considerable resources, which made all of this possible.

Did any of the less famous bands- Cressida, Gracious or Patto, get airplay in the UK at the time?

OW: Airplay wasn’t easy, in part because of the nature of the music- it didn’t fit into the format. Even Black Sabbath weren’t a “radio friendly” band, although once they charted, they of course got airplay. Cressida was a special case, because even though they were brilliant musicians they weren’t constantly playing live. And that made them more difficult to market in the touring to record sale relationship.

Although the “golden era” of Vertigo Swirl is usually considered 1969-1973, during which the label changed (first to a ‘small swirl’ and later to the so-called ‘Spaceship’ label), I was surprised to learn that Wyper left Vertigo shortly after the release of the Vertigo Annual 1970. While there were some great ‘Swirls’ released after Wyper (and Everett) moved on to RCA UK (and Dick Leahy went on to Bell Records), some of the later records just don’t hit the artistic measure of the best Vertigos. There were exceptions: one of my personal favorites, Patto’s Hold Your Fire, was first released on the ‘Swirl’ label after Wyper moved on (though Wyper had signed the band to Vertigo). They were produced by Muff Winwood, Stevie Winwood’s brother.

In total, there were less than 90 UK Vertigo Swirl albums released, depending on how you count them; in territories outside the UK, some, but not all of the UK Vertigos appear. In the States, there are not many U.S. pressed Vertigo Swirls and the masterings are obviously different. In New Zealand, albums like “In the Court of the Crimson King” appeared on the Vertigo label, though that album is more typically associated with Island Records, which first released it in the UK (and according to the vertigoswirl.com website, bears a catalog number typically associated with Island).[3] Many of these quirks of various releases worldwide are identified in the vertigoswirl.com web site mentioned above.[4]

Wyper had an amazing career in the music business before and after Vertigo- he started at EMI during the Beatles era, and went on at RCA (signing The Kinks and The Sweet and re-establishing the UK careers of Harry Nilsson and Perry Como as well as launching RCA’s Neon label), and then Essex, to work with artists like Joe Cocker, Joan Armatrading, T-Rex and Marc Bolan, The Move and classical guitarist John Williams. Despite his impressive career -even without the Vertigo label on his resume- I felt compelled to ask whether Wyper looked back at Vertigo as something truly special:

OW: It remains absolutely special to me; a huge creative satisfaction to launch a label from scratch, with a great team of people. It was rare to get an opportunity to start a label from the ground up with major resources, like those Philips had. As a creative achievement, and despite my working with other great labels and phenomenally talented people in the industry over many decades, Vertigo stands head and shoulders above all the others.

Even more impressive, Olav Wyper created a legacy of audio recordings as “high art” at a time when the music business was fast becoming corporatized, within the environment of a large multinational conglomerate. Even without knowing the man, I admire the hell out of him.

Olav Wyper is today representing film composers, directors and screen writers through his company, SMA Talent Ltd. He deserves our recognition and thanks for the creation of a body of record music that reflects a true summit, musically, sonically and aesthetically.

Bill Hart

March, 2015

______________________________________________________________

[1] There is also a “collector’s guide” entitled “The Vertigo Swirl Label “by Ulrich Klatte, a nice small format hardback that is itself out of print, as far as I know. Combined with the website mentioned above, it makes for a fairly good overview of the releases in the UK and elsewhere.

[2] Editor’s Note: The track listing for this record is, in a word, amazing. “Fresh Garbage” from Spirit appears with “Time of the Season” from The Zombies, “Statesboro Blues” from Taj Mahal with “Scarborough Fair” from Simon and Garfunkel. No small wonder this sampler sold well!

[3] Interestingly, Philips were distributing Island at that time, which made it even easier for a local executive to include a band’s album on the Vertigo label to give it appeal in that market.

[4] There are also some German Vertigos that are unique, i.e., they were not part of the UK Swirl canon of works, including two albums by the band Agitation Free.