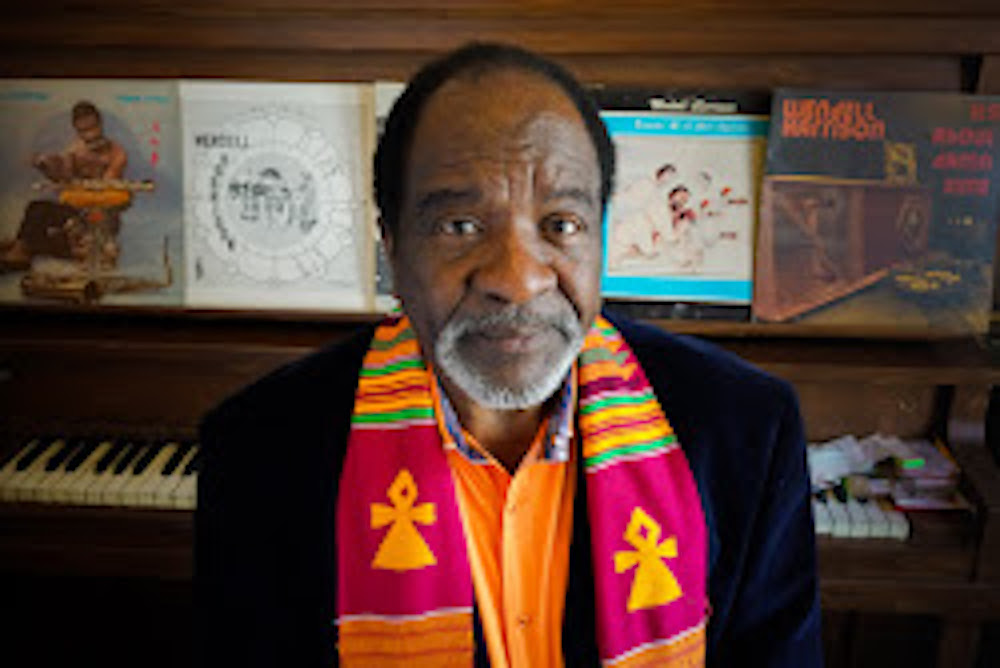

A MESSAGE FROM THE TRIBE- WENDELL HARRISON

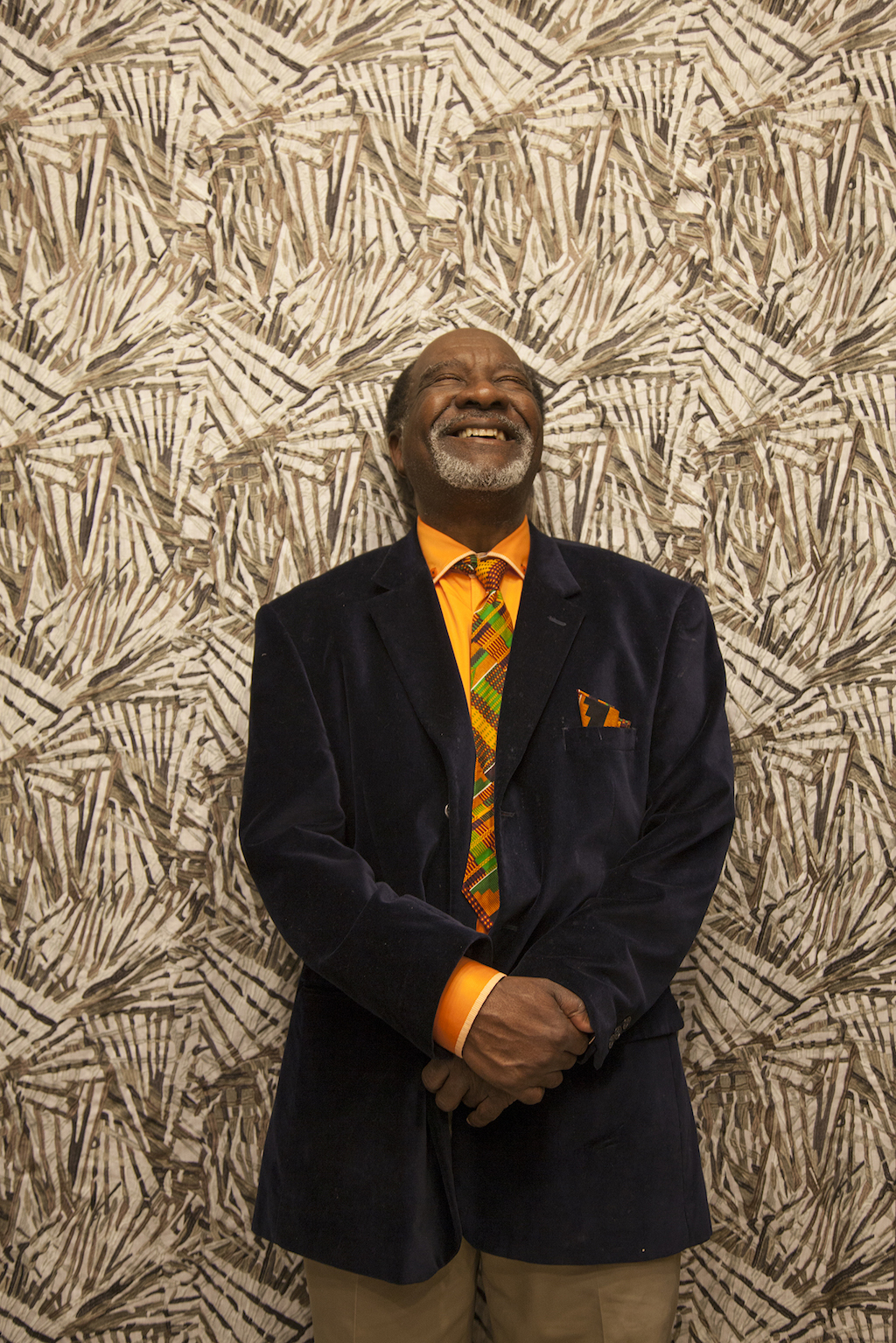

Wendell Harrison, Image by Noah Morrison, courtesy The Kresge Foundation.

Talking with Wendell Harrison is like jazz itself—a free flow of information, filled with nuance and detail, marked by contrasts and the occasional surprise, all connected when you stand back and get the shape of things. Wendell is a kind, warm man whose joy of life is evident in his words, music and all that he does: now an elder statesman of the Detroit jazz scene, Wendell is a teacher, a keeper of the legacy and an active musician and producer.

The years have taught Wendell focus, but his interests remain wide and diverse: from his early beginnings as a sideman, starting on the clarinet and migrating to the saxophone, to his eventual role as a bandleader and featured artist as well as a producer; co-founding the Tribe record label with band mate Philip Ranelin, publishing a music magazine and serving as an educator, Wendell Harrison became a voice for the community. At the time Wendell embarked on this journey, he had already devoted a decade of his life in New York and California working with such luminaries as Grant Green, Lloyd Price, Hank Crawford, Chuck Jackson, Sun Ra and Dionne Warwick. His return to Detroit in 1970 marked a turning point in his life and his music.

Wendell on the horn: Image by Noah Morrison, courtesy The Kresge Foundation

I originally reached out to Wendell to talk about A Message from the Tribe on the occasion of its recent reissue. It is a milestone spiritual jazz album from that cauldron of experimentation in the early ‘70s and was the first in a number of releases from the nascent Tribe record label. This was a time when many notable jazz figures turned away from commercial jazz (it wasn’t selling much anyway) and sought inspiration in their own experience; in the aftermath of the civil rights movement of the ‘60s, the black community emerged with an increasingly distinct body of work in music, film and other arts that spoke to, and reflected, the black experience in America.

Wendell was there at the beginning.

In 1970, after a ten-year stint in New York and California as a sideman and bandleader, Wendell returned to Detroit; he’s now been there for almost 50 years. Along the way, Wendell took a brief detour into rehab, having picked up a habit not uncommon among jazz musicians in the era. Even that offered opportunities to make music: Art Pepper was there, cleaning up, as was Esther Philips. Synanon, a famous, and somewhat controversial drug rehabilitation clinic in its day, had a roster of members that reads like a “who’s who” of music. Wendell appears on an album, The Sounds of Synanon,[1]released on Epic which includes more than a few familiar names.

The Detroit music scene was in flux when Wendell returned. Berry Gordy had pulled Motown out of Detroit for the sunnier climes of California. A lot of musicians who got good regular session work through the Motown hit machine were suddenly adrift. Wendell got work teaching be-bop at Metro Arts, married and worked to promote the local jazz scene.

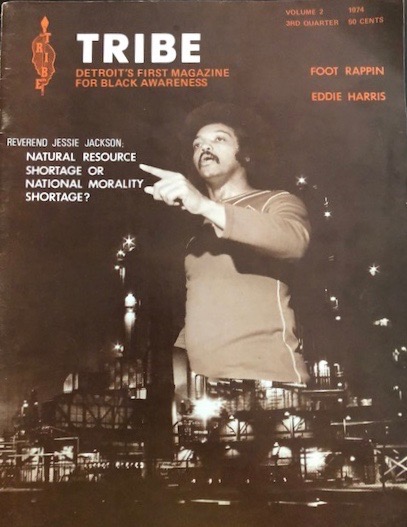

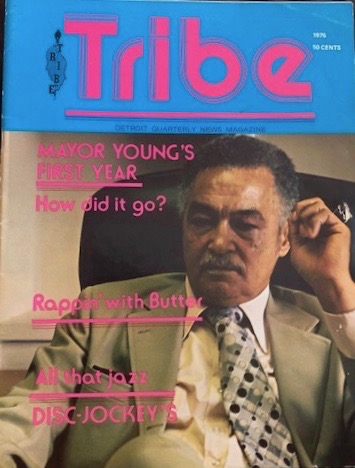

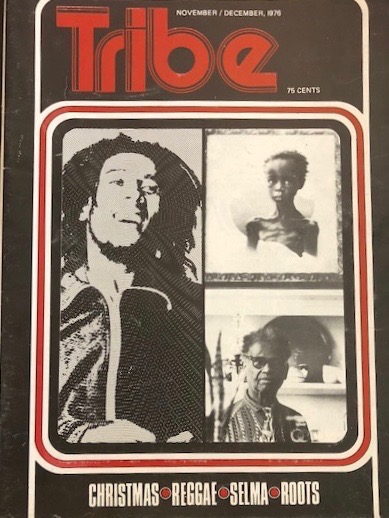

He produced concerts and musicals that were financially supported by a program guide. This guide was funded by advertising from business and corporations, and eventually transitioned into Tribe Magazine, which addressed arts, music, social economic and political issues of the black community.[2]

Tribe Magazine cover images:courtesy Wendell Harrison

Wendell hired journalism students from nearby Wayne University; the kids could write, and were very socially conscious; writing for Tribe gave them a credential that they could use as a stepping stone to advance their careers as writers.

The Tribe record label came into existence as a natural outgrowth of performing and recording, rather than some concerted effort to commercialize the music. According to Wendell:

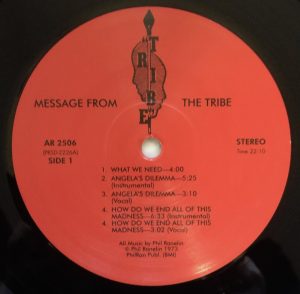

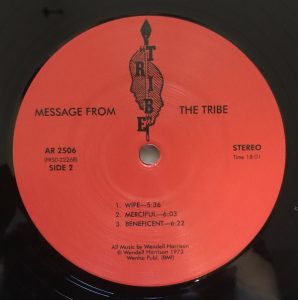

At first, we really weren’t focused on the record business. We were playing live shows. One was a musical that we had staged at the Detroit Institute of Art. It had music, skits, and poetry. We recorded it but weren’t really very knowledgeable about how to release it. The original copies were of entire show, a huge amount of material squeezed onto one LP. That was the first LP version of Message from the Tribe, released on the Tribe label. As I recall, there weren’t ever any gaps or needle drop points between the individual compositions or tracks. The album was long continuous sides of music compositions with no break between movements. We pressed up around a thousand of this first production. We had this production re-mastered after many requests from radio DJ’s.

When we had the record recut, we re-mastered it into two separate albums, Message from the Tribe and Evening with the Devil.

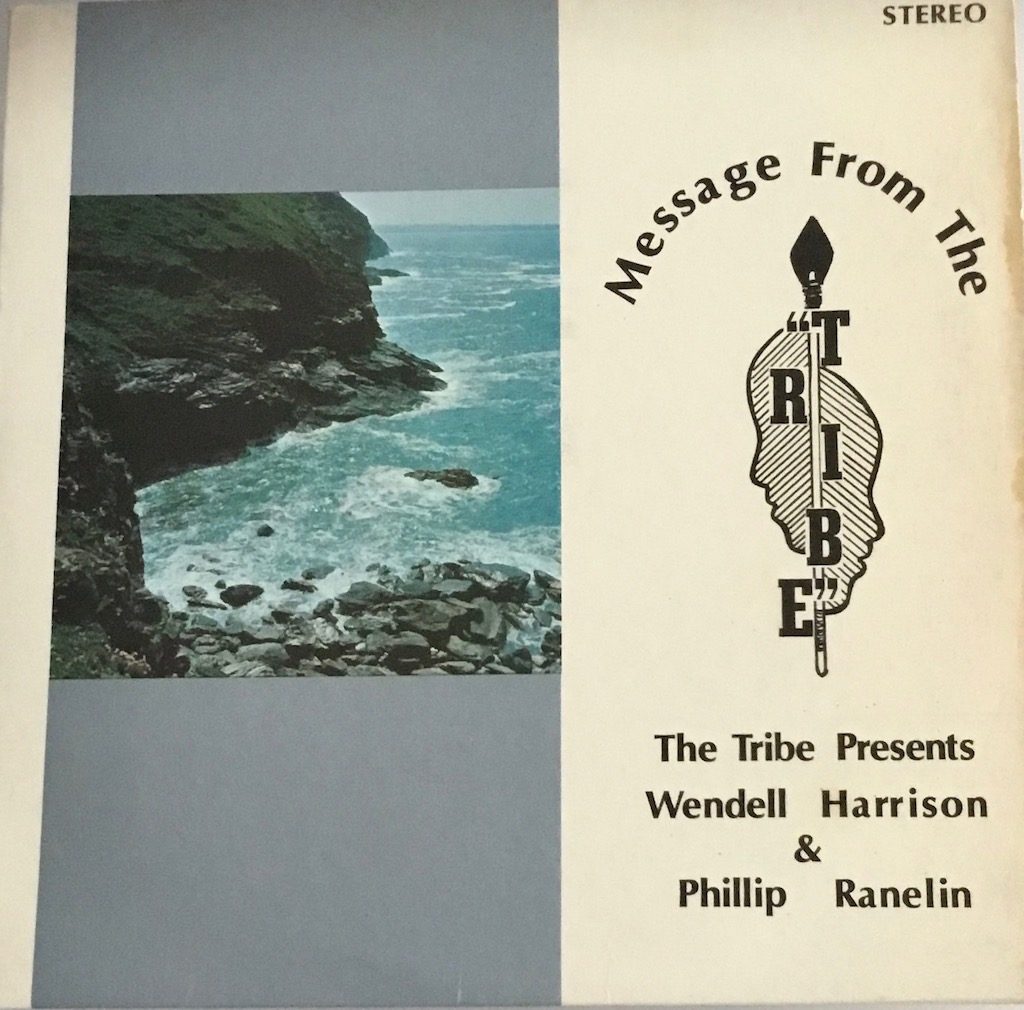

First Pressing- Message from the Tribe

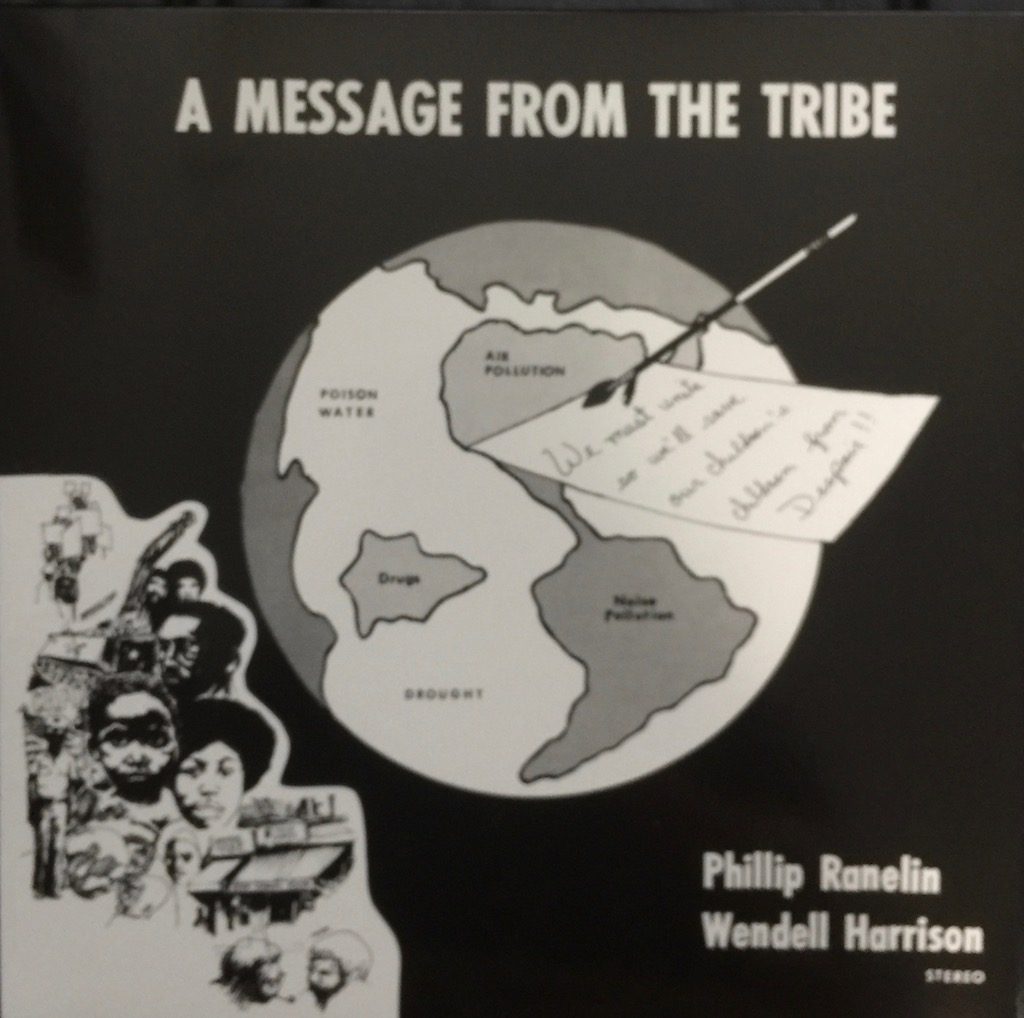

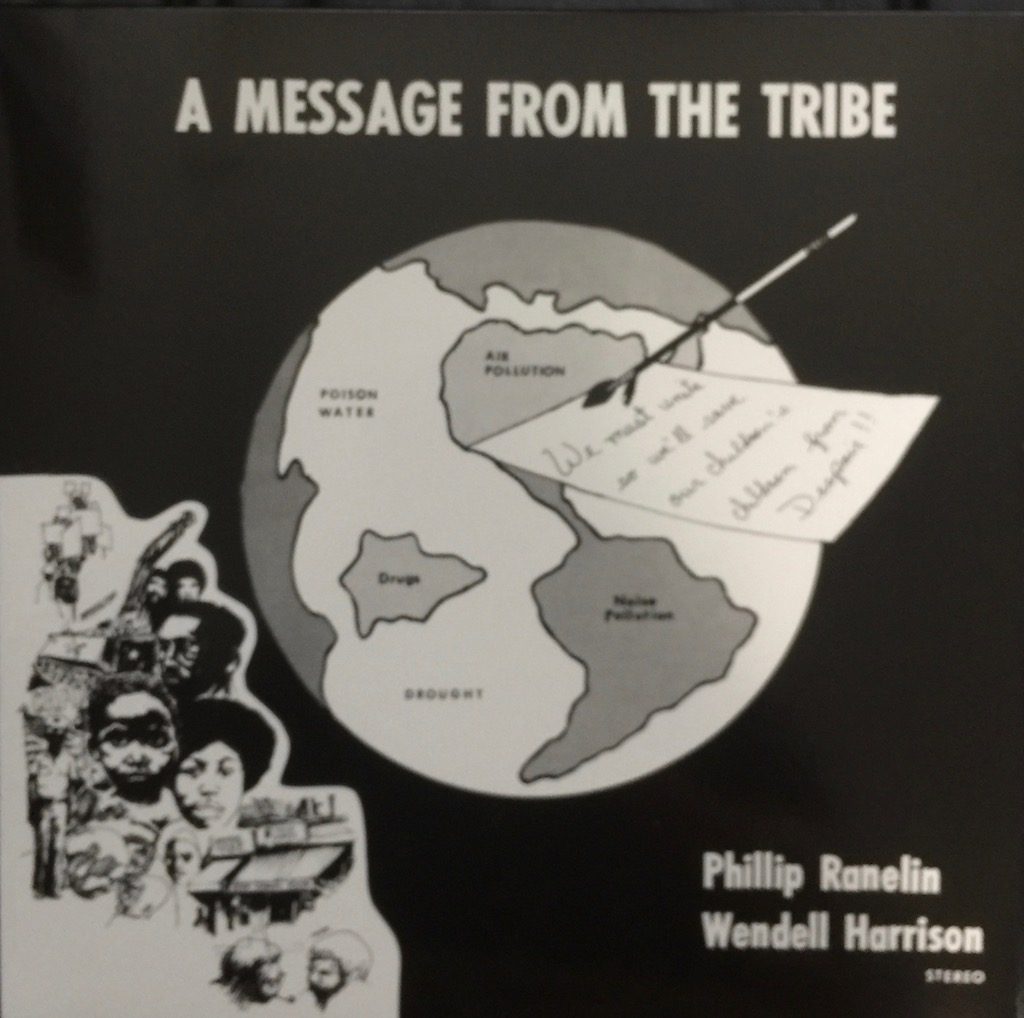

The cover changed on this second version of Message from the Tribe (1973), from the image shown above (1972), to the globe drawing shown below:

A third version of the album was released in 1974 with cover art consisting of drawn likenesses of the artists.[3]Tribe was now not just a magazine but a record label and went on to release seven LPs and three 45s, not counting compilations and reissues.

Wendell explained that the formation of a label was essential for commercial distribution:

We needed a label—in order for distributors to pick you up—they didn’t want to deal with a single one-off record. That got us into the chain of distribution and offered us radio play—there was interest in the “catalog”—what were we going to release next?

Eventually, we built the label from a local to a regional and eventually a national distribution base. Our distributors on the East and West Coast were selling a pretty good number of records. I found out that they were shipping to Europe and Japan. So, at some point, Tribe became international. But, at the same time, the communities for our music were at a local level.

In this era, distribution was relatively easy:

People were receptive to it, part of it was supporting local artists and businesses, and part of it was rebelling against the big corporations–

Radio was promoting us because we were part of the community—

The community knew us—we had recorded for major labels—they not only knew who we were- but dug the fact that we were doing our thing rather than working for the big companies. So, we had a lot of support.

Tribe Reunion: Marcus Belgrave, Wendell Harrison, Philip Ranelin. Image: W. Kim Heron, courtesy The Kresge Foundation.

There were other similar models:

We functioned like a ‘collective’ – so artists kept their rights—all the principals played on each other’s albums— there was of course Strata East and Black Artists Group in Saint Louis—as well as the JCOA (Jazz Composers Orchestra Association) in New York; there was also Cadence Jazz, found by Bob Rusch, who produced a magazine as well. Bob Koester, who ran the Jazz Record Mart in Chicago also had the Delmark label which focused on Chicago blues but he acted as a center of gravity there for the jazz scene.

The musicians who performed on the Tribe releases were ensemble players who would support each other, appearing as featured artists on their own records and playing as sidemen on other Tribe releases. The “regulars” included: Marcus Belgrave, Philip Ranelin, Harold McKinney,Ron Brooks, Doug Hammond, Roderick Hicks and, of course, Wendell Harrison.

This collective also performed regularly in Detroit at places such as the Detroit Institute of the Arts, the University Of Detroit, the University Of Michigan, Michigan State University, Wayne State University, the Oberlin University-Ohio Saginaw Festival, Detroit Jazz Festival, and various venues in the Midwest.

Wendell eventually started working overseas- in the ‘80s, he travelled to Africa and in the ‘90s, the State Department underwrote tours with prominent artists. This was a continuum of the Jazz Ambassadors program started in 1956 by Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.

Eddie Harris and Woody Shaw were among the musicians Wendell worked and travelled with in the ‘80s. Wendell worked with Leon Thomas, a gifted jazz singer, for thirty years. (Thomas, in turn, performed with everyone from Pharoah Sanders to Santana).

Wendell had formed the Rebirth Corporation in the late ‘70s and sought grants for music education and cultural exchange. Wendell worked with Harold McKinney (another Tribe “regular”) touring colleges and universities in the Midwest and South. Tribe went to Paris in 2009, on the heels of a record produced by Carl Craig, on Craig’s Planet E label. (Carl Craig’s father used to help Wendell distribute the original Tribe record releases and magazine).

Although he started playing the clarinet in 1950 and switched to alto saxophone in the tenth grade, and switched again to tenor saxophone in the twelfth grade while attending high school, the tenor saxophone became Wendell’s main instrument before he moved to New York. Wendell added the soprano saxophone in the 80’s. That instrument was stolen along with his car; the car was recovered, but sax was not. At this time Wendell started back to playing the clarinet, along with tenor and flute.

Wendell and Noah Jackson: courtesy W. Kim Heron

By the late ‘80s, vinyl was no longer in vogue—everyone—the labels, the distributors and the retailers, had switched to the CD format. Wendell thinks it was a mistake for the labels to simply drop vinyl altogether, but with the death of vinyl, he found another niche; rather than having LPs manufactured and distributed, Wendell’s companies—Tribe, Rebirth and his Wenha label—started licensing the masters to third parties for reissue on CD.

By the ‘90s, Wendell produced the Kim Heron show on WDET bringing in artists to perform live, among them: Andy Bey, J.D. Allen, Steve Turre, Reggie Workman, Nnenna Freelon and Paquito D’Rivera all appeared and performed. Kim Heron, the host, was involved in the wonderful book about Wendell published in connection with his Kresge Eminent Artist recognition, below. Wendell still has the master tapes of those shows, which probably contain some real gems.

A fairly complete discography of Wendell Harrison’s work can be found on his site, and covers not only early recordings on Atlantic, but the albums he produced on the Tribe, Wenha, Rebirth labels, including A New Message from the Tribe (2016) and four other records featuring his wife, Pamela Wise, a pianist/composer of significance in her own right.

http://www.wendellharrison.com/recordings/4594361109

Harrison hasn’t stopped. He earned his masters degree in communications last year and wrote and published a book on marketing and promotion for the independent musician. During the interviews for this piece, scattered over the course of a few weeks, Wendell travelled to Rochester to plan a three-city tour in upstate New York (Rochester, Syracuse, and Buffalo), including workshops, concerts and media interviews promoting his music.

Wendell at the Michigan Design Center, Julie Pincus, courtesy The Kresge Foundation.

The Kresge Foundation honored Wendell Harrison this year as the recipient of the Eminent Artist Award in 2018. A beautifully written biography filled with photos spanning Harrison’s life and career can be found here. Hard copies of this booklet are available at no cost from Kresge—just send an email to [email protected]. While you are at it, get on their mailing list.

The Pure Pleasure Reissue (2018)

Pure Pleasure reissued A Message From the Tribe at the end of August, 2018. This was the first record to appear on the Tribe label, although, as noted above, there are several variations of the release.

The Pure Pleasure reissue utilizes the cover and tracks of the 2nd version of the album. (The last issue of Evening with the Devil, which was separated from the original Message from the Tribe as a freestanding album under its own title,appears on P-Vine Records from Japan in 2009).

For me, what started as a fairly straightforward review of this album (with artist interview) led me to a much more in-depth exploration of the life and career of Wendell Harrison. My sense is that this is how things often work in Wendell’s world—one thing leads to another, and before you know it, you’ve learned and experienced far more than expected. That was certainly the case for me, in writing this piece. Let’s turn to the music on this album, since that is where I began:

Side 1

The album opens softly, horns joined in a plaintive refrain while Jeamel Lee’s vocals, supple and easily within her range, deliver the message “What We Need” against a quiet, funky beat. The song winds down with a cymbal flourish– an inner minor melody from the horns emerges with deep percussive drum rolls in the background.

The opening track merges into “Angela’s Dilemma”—an instrumental that starts with a funereal dirge—you get the sense the players are restraining themselves, muted and controlled rather than showing their stuff, when Wendell picks it up playing trills and flares on the sax. Vocalist Jeamel Lee jumps back in for the second part of “Angela’s Dilemma,” which carries the same motif as “What We Need” but everything is less restrained now. The bass (both acoustic and electric) is just outstanding, underscoring the reach of Lee’s voice.

We roll right into “How Do We End All of This Madness” with a funk percolating on electric piano and bass, horns popping in and out until they get their footing, and then we are in a fugue; the electric piano goes wild, and the drums signal the horns to charge in. It’s easy to follow the parts; each horn has a distinct sound and there is harmony even in disc(h)ord. We are listening to virtuoso players here, at the top of their game.

Give this record some gas and it won’t disappoint—lots of little things going on among the horns, percussion and bass but following a repeated riff /E/ GAB AGA/–and the male vocals jump in, the horns having a triumphant conversation among themselves in the near ground.

Side 2

When Wendell and Phil split up and re-mastered the original Message from the Tribe into two albums, side one of what is now considered the standard version of the album is Phil Ranelin’s work, taken entirely from the original album. Side two consists of three compositions Wendell wrote to fit the revised album format, rather than adapting the material from the original version of Message; instead, those performances resurfaced on the separate album, Evening With the Devil.

The three tracks on side two of Message are: “Wife” a funky excursion of electric piano with horn flourishes that opens into a flute solo (Wendell) against a slow treading bass line; the stick on cymbal strikes and snare have impact and resound in a harmonic envelope that sounds very real. The horns form a border, reminding where the edges of the song are, but by this time the flute has vanished.

“Merciful” opens with flute, what sounds like a mix of chime-y electric piano and Marcus Belgraves’ flugel horn which turns a light melody into a slow descent into a bigger, badder band—the bass here keeps the pressure on—as the instruments come into focus, and ultimately reprise the flute’s melodic opening, but now the flute is playing across the notes—minor keys and out.

“Beneficent” is like bossa nova but it quickly leaves the tropics for an urban sound—horns vibrant and alive, some slick drumming, including high-hat tricks and that delightful fuzzy-funky woodiness of the electric piano. The sax goes full bore on this one and brings the band in behind it.

The Pure Pleasure reissue is a fine sounding record and an easy (and far cheaper) alternative to an original pressing—the 2nd(and 3rd) versions of A Message from the Tribe, while not quite as rare as the fully-loaded original, are still quite expensive. Although Pure Pleasure never responded to my inquiry regarding sources used, Wendell assured me that the master tapes in his possession were not used.

Assuming that a digital source was used, it is quite well done and consistent in quality with a lot of the better digital transfers I’ve heard as a basis for cutting vinyl. I’m not going to get too hung up about the “all analog” mantra if the end product sounds good. And it does.

I’m glad to see this revival in spiritual jazz. It’s not only gotten me back into listening to jazz but was a turning point for getting me beyond straight ahead styles (in which I had largely lost interest). It also opened a lot of new musical pathways that deserve further exploration: the mixture of soulful singing, funk and avant-garde instrumentation. There are all kinds of influences coming to the fore, from the Afro-centric and exotic polyrhythms to the harder driving funk that became a genre unto itself. This period in particular is rich in possibility, because it is fresh and new and adventurous. You can hear it in the playing. And it’s a hell of a lot of fun to listen to.

Although Wendell Harrison’s career has spanned several different eras of jazz, I think it’s safe to say that he really hit his stride in the early ‘70s, starting during the period when A Message from the Tribe was first released. His continued maturation as a musician coincided with his greater involvement in the community as a producer, label owner, magazine publisher and educator. In many ways, Wendell became a center of gravity for the spiritual jazz movement in Detroit beginning in the early ‘70s. As of this writing, he’s still playing, doing workshops, teaching and exploring new ventures to engage younger generations. Bless this man. He’s certainly given us a lot to cherish.

Bill Hart

Austin TX.

September, 2018

_______________________________________________

[1]https://www.discogs.com/The-Sounds-Of-Synanon-The-Synanon-Choir-The-Prince-Of-Peace-A-Rock-Jazz-Cantata/release/7144871

[2]I did not have much luck finding vintage copies of Tribe magazine for sale, though I did find a few sites, including soulstrut and voices of eastanglia which collected some additional cover images. The magazines are a fascinating capsule of the time.

[3]See https://www.discogs.com/Wendell-Harrison-Phillip-Ranelin-A-Message-From-The-Tribe/release/3989204

My thanks to:

Wendell Harrison for his time, knowledge and good humor in answering my questions (along with writing and playing a lifetime of killer music that I’m still exploring); Pamela Wise Harrison (whose music I have not yet begun to explore) for helping me put the pieces together; and Kim Heron for help with photo clearances and information.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.