I’m haunted by Chris Whitley. We’ve had our share of gifted musicians— far too many to recount here– who died young, leaving a legacy of recordings that are honored today through reissues, deluxe boxed sets and retrospectives (in word and film). Labels can effectively mine a catalog, make a profit where little was had at the time of original release and in the process, keep the music alive for new generations of fans.

For various reasons, Chris Whitley doesn’t yet benefit from that kind of visibility. His work really deserves greater recognition and a revival. There have been tribute concerts featuring such luminaries as Vernon Reid and Eric Johnson; Whitley’s Wikipedia entry logs Keith Richards, Dave Matthews, Tom Petty, Iggy Pop, John Mayer and Springsteen among his many admirers. And there is a fan base that stretches from Texas to Vermont to Belgium and Germany. But, apart from his first album and the publicity surrounding its release (inclusion of one song in the soundtrack of the film Thelma & Louise didn’t hurt nor did an appearance on David Letterman), Whitley was successful by conventional measures only briefly.

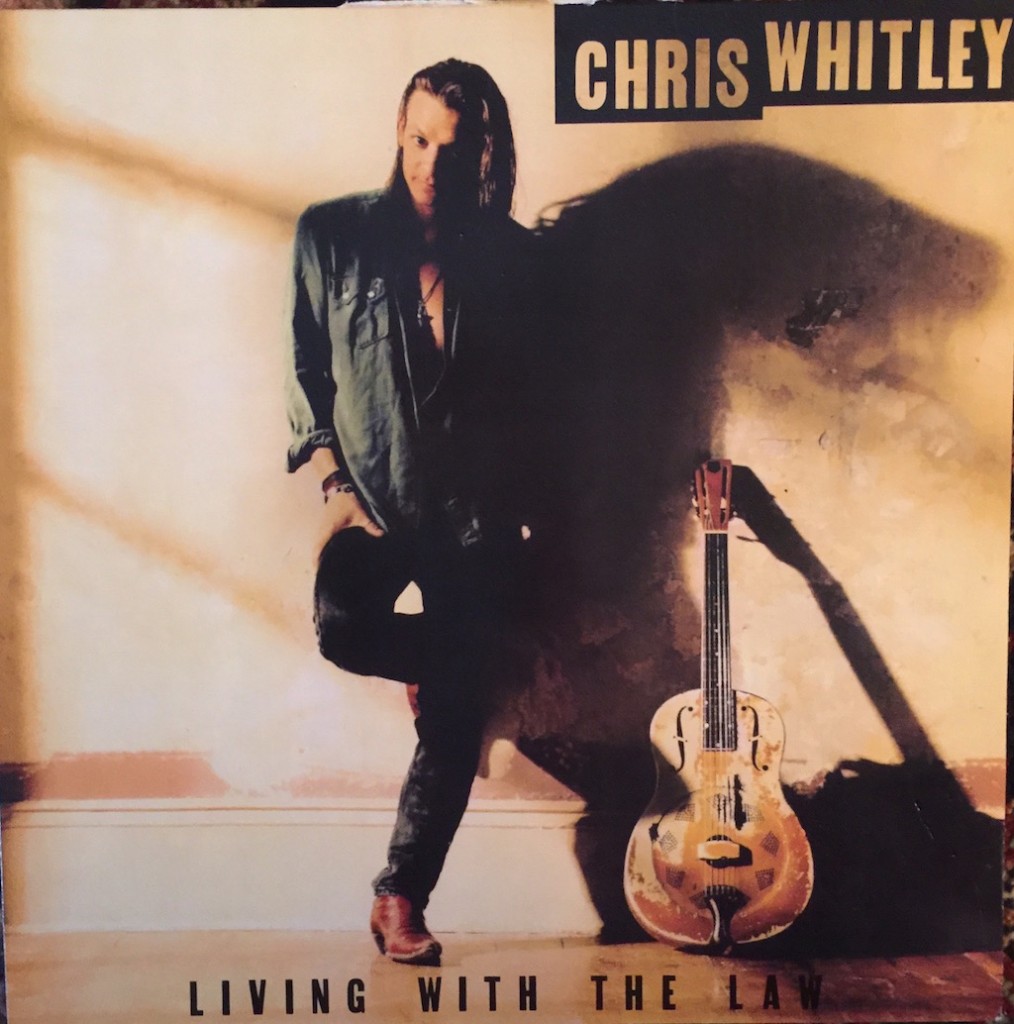

Whitley’s debut, Living with the Law, was released by Columbia (now Sony) to widespread critical acclaim. He toured with Tom Petty. Whitley even earned a back-handed compliment from Robert Christgau, the self- proclaimed “Dean of Rock Critics” as a “trad wet dream.”[1] Living with the Law is a great album, but not because it depended on familiar blues conventions- in fact, in an interview after its release, Whitley said he respected the blues, but found a lot of it “very boring.”[2]

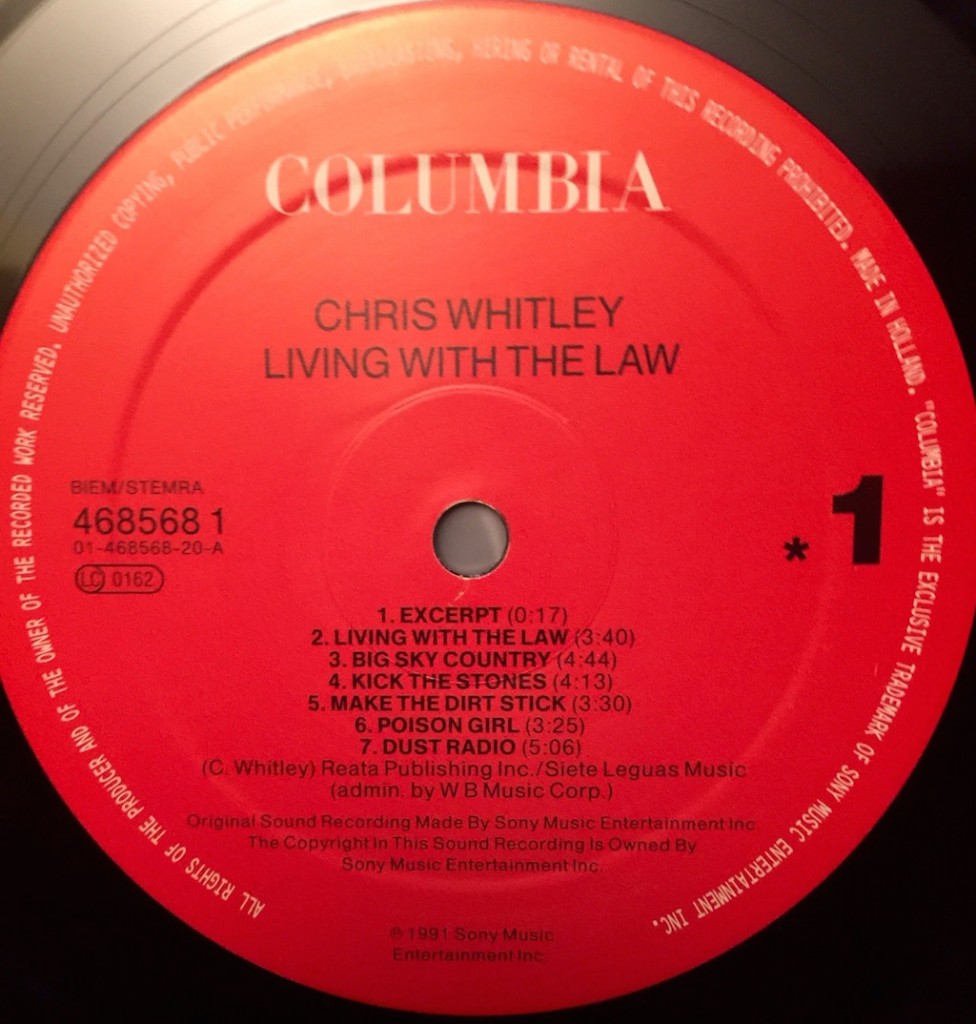

But, for most listeners, it probably makes sense to start with Living with the Law. Daniel Lanois helped Whitley secure a contract with Columbia Records, and the album, produced by Malcolm Burn, was recorded at Lanois’ home in New Orleans. The record was mastered by Greg Calbi and my copy, a Columbia pressing from the era of original release, was manufactured in Holland.

Despite the characterization of this record as “traditional/blues,” it isn’t. I’m not trying to be fussy here, but when the accepted wisdom is that Whitley went from a great “trad/blues” sound on Living with the Law to something completely different on his second album, discussed below, somebody missed the deeper clues into what Whitley was up to. Granted, with hindsight, it’s easier to figure out. You can hear the drive behind these songs: listen to “Make the Dirt Stick.” You can hear that resonator guitar hum and shimmer, but it’s also edgy; even “Poison Girl,” which has a “pop” quality and depends on slide and swagger, has Whitley singing in his characteristic falsetto and the guitar is on the cusp of distortion. I don’t want to make too fine a point of all this- but even “Dust Radio” depends on overloaded guitar sounds, and some hard rocking lead lines.

“I Forget You Every Day” takes the “traditional” elements and turns it all into something that doesn’t quite fit under one label- there’s a hint of hard distorted rock buzzing throughout. A psychedelic influence is unleashed on “Long Way Around.” I guess as long as we have that resonator guitar,[3] and a song about prison, the box got checked. Despite being the most accessible, the most “comfortable” and the most widely known album among Mr. Whitley’s records, I don’t consider it a “trad/blues/roots” album. I also still find new riches in it every time I play it.

Whitley threw almost everyone for a loop with his next album, Din of Ecstasy in 1995, a discordant mix of jagged, distorted rock that the LA Times observed likely “… will alienate Whitley’s first round of fans.”[4] Had anybody been paying attention, Whitley wasn’t all blues, all the time; aside from the cues in Living with the Law, his years spent in Belgium gave him more than a taste for Euro-electronica, dance music and synth-pop.[5] To Whitley, it was a continuum: “ ‘I don’t want to disappoint somebody, but if it happens, it’s like they didn’t really get the first one,’ he says of the potentially alienated fans. ‘It’s like they just picked up on the superficial aesthetic.’”[6]

This album is a challenging listen, and a radical departure in form from the far more accessible Living with the Law, but it contains superb guitar work and the tracks have a beautiful internal symmetry within the distortion and discord. It’s certainly not a polished product, and doesn’t fit neatly into any genre. Din developed a following over time, but upon release, it was not well received and did not do well commercially. Christgau gave it a “bomb” symbol, which I gather was not a compliment. The album deserves a reassessment today. Unfortunately, it was never released on vinyl, so you’ll have to rely on digital media for this one. (Bob Ludwig mastered it for those concerned with such things).

Whitley hung in with Sony (or the other way around) for one more album, 1997’s Terra Incognita, before artist and major label parted ways. This, his third album, was viewed as a “big improvement” over Din, but at the time, it seemed to reflect an artist still adrift, in search of a mooring.[7] Some critics viewed it as a welcome return to more conventional “song” forms, but it has adventurous, unconventional guitar playing. I don’t regard this album as an attempt at commercial compromise, but part of a continuing exploration. Whitley was still pushing boundaries here.

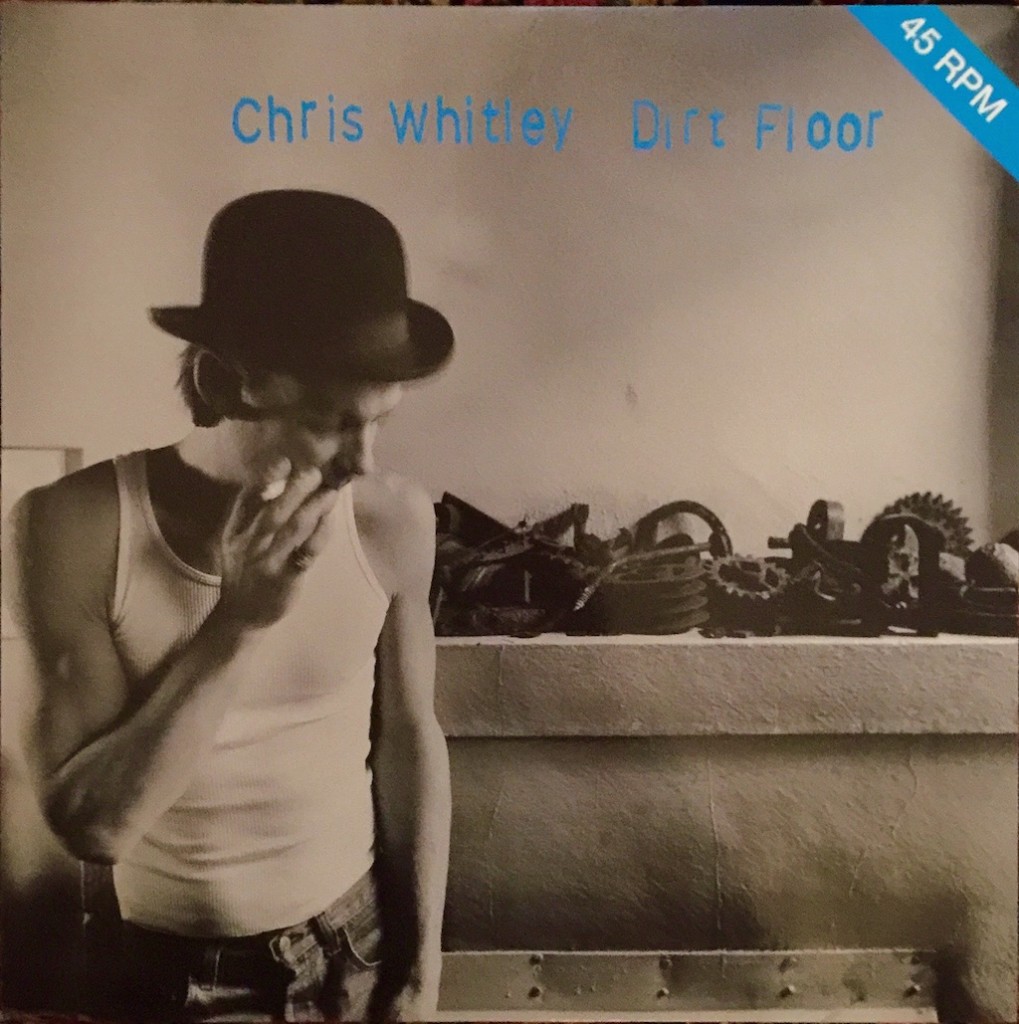

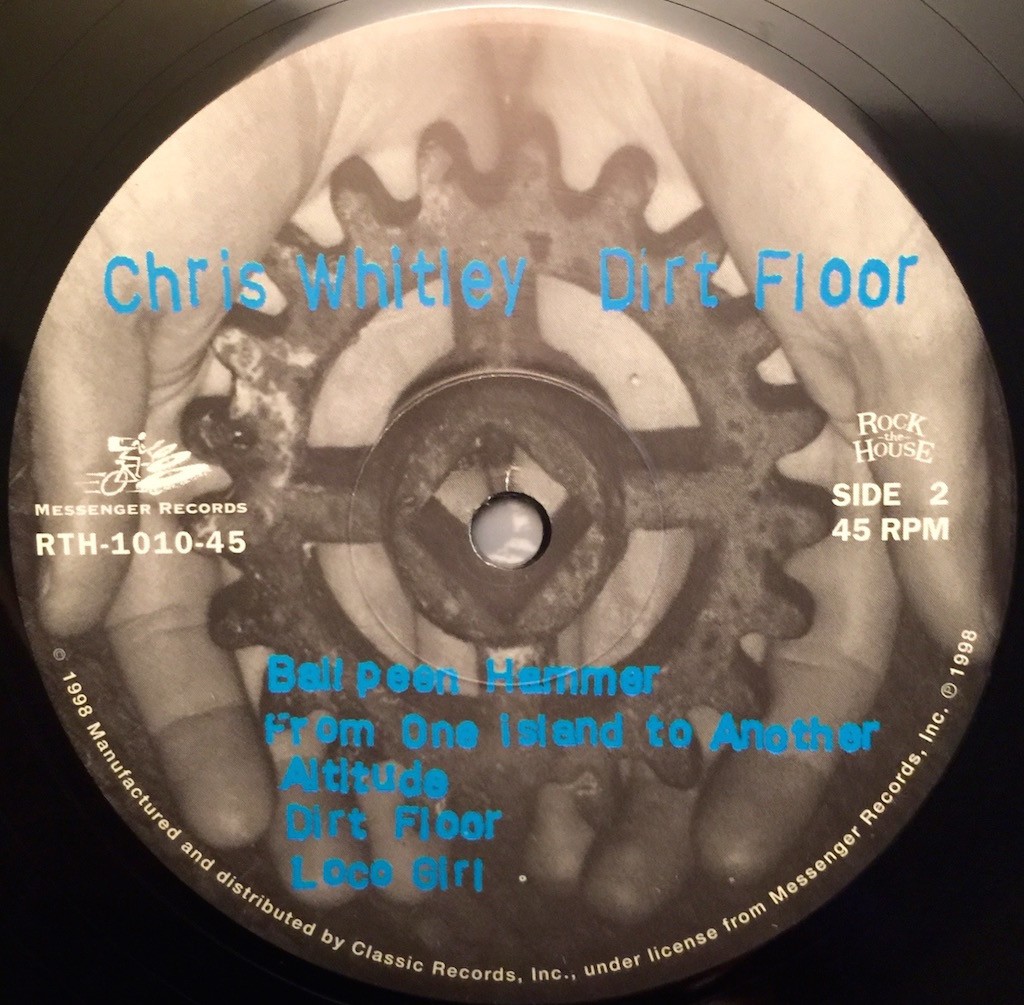

Whitley may have been adrift commercially, but not musically. Signed to a small New York City label, Messenger Records, Whitley next delivered the magnificent Dirt Floor, released in 1998. Classic Records (a label usually associated with high-end audiophile remasters) released it on a 45 rpm album, taken from a simple two track analog recording made in a barn in Vermont. The title track alone, little more than two minutes long, is worth the price of admission if you can find a copy. There is a rip to Whitley’s voice that doesn’t sound like an affectation, and I get goose bumps every time I listen to this track- it has a stunning ability to reach through the recording and touch you on a visceral level- and I’m not talking sonics here (though the recording is a killer).[8] There is also something absolutely transcendent about his voice here that, combined with the resonance of the guitar strings, is both ethereal and raw at the same time. This song and performance move me like few others. If Christgau was searching for authenticity, it’s here, on this album, in spades.

There were more albums-on yet other small labels- before Whitley returned to Messenger, along with some live releases. (I’m not going to review all these recordings in depth now, but may do so in the future). Most of his discography was not released on vinyl (to the best of my knowledge), save for Living with the Law, Rocket House, Dirt Floor and a smattering of other releases that may take some digging.[9] All this material should be reissued. I appreciate that various record labels probably own the masters, but wouldn’t a boxed set be nice? Sony/Legacy has done some fine reissues, using QRP to press them. Maybe, if the film takes off, see below, the time will finally be right for someone to pull this together.

You also can hear Whitley on Cassandra Wilson’s Blue Light at Dawn, making the track “I Can’t Stand the Rain” hum and shimmer. (Whitley makes an appearance on Wilson’s New Moon Daughter as well). Wilson was produced by Craig Street, who produced Dirt Floor, see note 8.

Whitley seem less concerned with style, form or lyric- the “feel” of the music and conveying something on a gut level was more important than the end product. That is what the recordings reveal- his voice rang true and his tone and dexterity on the guitar were mesmerizing. Although he was most often associated with a National Triolian,[10] he pushed the limits of that instrument beyond the usual blues/roots conventions. He also employed falsetto in ways that give some of his work a haunting quality- much like the original, early Skip James stuff (when James was at his prime).

But Whitley’s real link to the blues is less about genre than about genuineness in my estimation- something that can’t be faked. Maybe that’s why Living with the Law, his most polished and accessible album, doesn’t reveal the full measure of this artist. (As mentioned above, you can hear clues, but we have the benefit of time and the context of a larger body of work from which to assess this).

♦

At the end, after a break-out debut, and a series of less accessible albums on small labels, Whitely was sick, run down and still struggling; he abruptly canceled a tour and died of lung cancer shortly thereafter, at the age of 45. Sadder still is the fact that most of his work languishes, except among his coterie of fans. Long in the making, a film, Dust Radio: A Film About Chris Whitley, may finally reach audiences after a number of years of work by two different filmmakers who eventually combined their efforts. Perhaps this will finally help Chris Whitley get his due.

While we await a revival of his work, we can enjoy one other gift from Whitley (and his ex-wife, Hélène Gevaert): daughter Trixie Whitley, who has made some wonderful records already mentioned here.[11] Both manage to “break the fourth wall,” in the sense that they punch through the boundary of the recording to involve you in their performance. When it happens, it is eerie, and you realize that this is what recorded music should be all about. Ultimately, Chris Whitley is proof that genres don’t matter.

More about Whitley as and when….

Bill Hart

July 27, 2015

___________________________

[1] See “Reality Used To Be a Friend of Ours,” Village Voice, Mar. 3, 1992. As best I can tell, Christgau was trying to reconcile the commercial and popular success of indie-based acts such as Nirvana with musical authenticity. In fairness to Whitley, if not Christgau, there was already a backlash against the slick corporate “pop” of the late ‘80s that had primed audiences for something more gritty and real.

[2] See Graham Reid, “Chris Whitley Interviewed (1991): The Law man living with the lore,” Elsewhere, posted May 24, 2010.

[3] Whitley is recognized for employing unusual tunings, which are a subject of study among guitarists. He also played the instrument unconventionally, see article at note 10, below.

[4] Lorraine Ali, “The Jagged Edge,” LA Times, April 16, 1995.

[5] See The Belgian Pop & Rock Archives, overviews of A Noh Rodeo and Kuruki .

[6] “The Jagged Edge,” Id. note 4, above.

[7] See “Chris Whitley- Terra Incognito,” No Depression, February 28, 1997.

[8] Dirt Floor was produced by Craig Street, who values “early takes,” simplicity and great tone. He is credited with a slew of superb sounding records. See Mix Magazine interview.

[9] There are a few singles and EPs, as well as an album entitled Reiter In by Chris Whitley & Bastard Club that was apparently limited to 1,000 copies. Dislocation Blues, with Jeff Lang, was apparently released on vinyl but I have yet to track down a copy. The only album currently in print on vinyl, as far as I know, is a recent Music on Vinyl reissue of Living with the Law.

[10] See All Things Chris Whitley. This site is a treasure trove of material about Whitley and worth exploring.

[11] See “I’d Rather Go Blind” and “Black Dub.”