Introduction

I’m fascinated by that “turning point” in popular music in the mid- ‘60s, when mainstream music was transformed from sonic pablum to electric rock, folk and blues. Of course, the Beatles (and others from the first British invasion) had a huge, irreversible influence, but other things were stirring Stateside, including a reconnection with rural blues.

No band had more involvement in this transformation than Canned Heat. Members of Canned Heat were deep blues enthusiasts involved directly or indirectly in the rediscovery, with others, of such legendary, forgotten bluesmen as Son House and “Skip” James. See Sidebar: Rediscovering the Blues.

John Fahey (a hugely influential figure in the blues revival) introduced Al Wilson to Bob Hite, who formed the core of Canned Heat. Henry Vestine signed up as the band transitioned from hillbilly “jug band” to blues boogie band. All of them were ardent fans of early blues; earnest scholars, record collectors, and active participants in the rediscovery of the blues.

The band was morphing in its early days, with changes in additional members, and its first album, produced by Johnny Otis was not released until later. After locking in bassist Larry Taylor, and signing with manager Skip Taylor (who is interviewed as part of this piece, see Interview with Skip Taylor), Canned Heat performed at the now legendary Monterey Pop Festival with the likes of Big Brother, the Steve Miller and Paul Butterfield bands, among many others.[1] Drummer “Fito” de la Parra then joined.

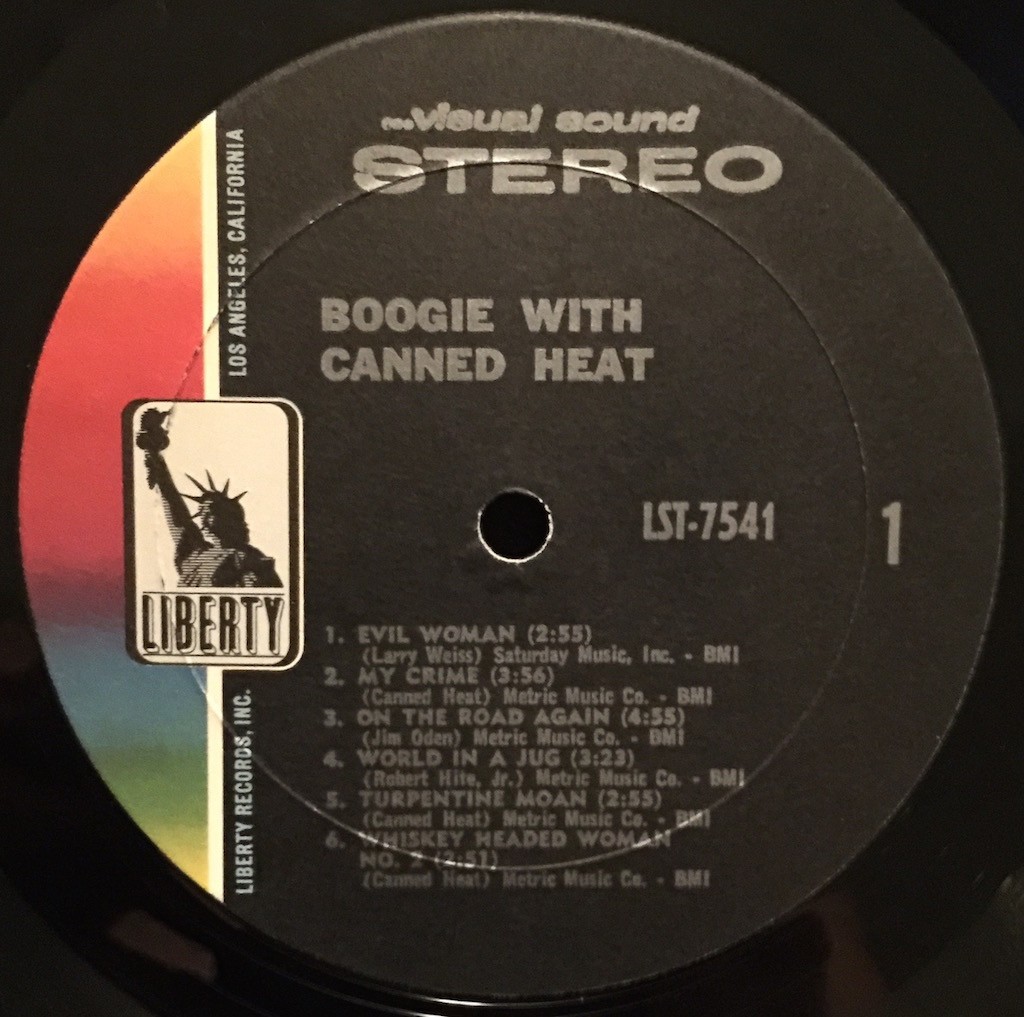

This, the classic line-up, recorded their breakout album, “Boogie with Canned Heat,” on Liberty Records.[2] The album, released in January 1968, contained the radio hit, “On the Road Again” and is essential in the Heat canon.[3]

THE RECORDS

Boogie with Canned Heat:

This album is a perfect introduction to the band: starting with a slow psych-rock driven blues, “Evil Woman” (which sounds terrific on my old Liberty pressing); then, “My Crime”, a very “Muddy”- style Chicago blues; this is not a pale facsimile of Chicago blues –it stands on its own. That leads to “On the Road,” a proto-boogie tune that takes you back in more ways than one; it’s not just a “hippie” flashback, but conjures a more distant past. (The more I understand the older blues, the better I appreciate Canned Heat). There is a constant droning “shimmer” behind the three-note chord framework, along with what sounds like sitar (but is a tambura- I had to look it up) that gives the track an otherworldly quality.

Hardcore blues, psych-inflected guitar with a muted but sweet, rich tone that descends into distortion or rings clear, a beat that makes you want to dance (or climb on your Harley and raise some hell), with great vocals, harmonica parts and just the right mix of horn parts. Nothing here sounds the same from track to track- it’s a showpiece of different blues styles. Sunnyland Slim makes an appearance on “Turpentine Moan” and Dr. John adds piano and some horn arrangements. If you like the slow, stinging guitar blues, listen to the track “Marie Laveau”: -Henry Vestine owns this, and man, what an under-appreciated guitarist!

“Fried Hockey Boogie” takes that road you’ve been down many times- you’ll hear a few familiar riffs as part of this jam fest- Larry Taylor, the bass player, is driving the bus but everybody throws down at some point. (One site cautions readers that the song is not about “hockey.”)

This album is as good a place as any to dive into Canned Heat. “On the Road” put the band on the commercial map; strong touring throughout the U.S. and Europe bolstered the bands’ commercial success. Constantly performing tightened the ensemble and earned them another hallmark –consistency—that is evident from the “live” tracks on Living the Blues, their next album.

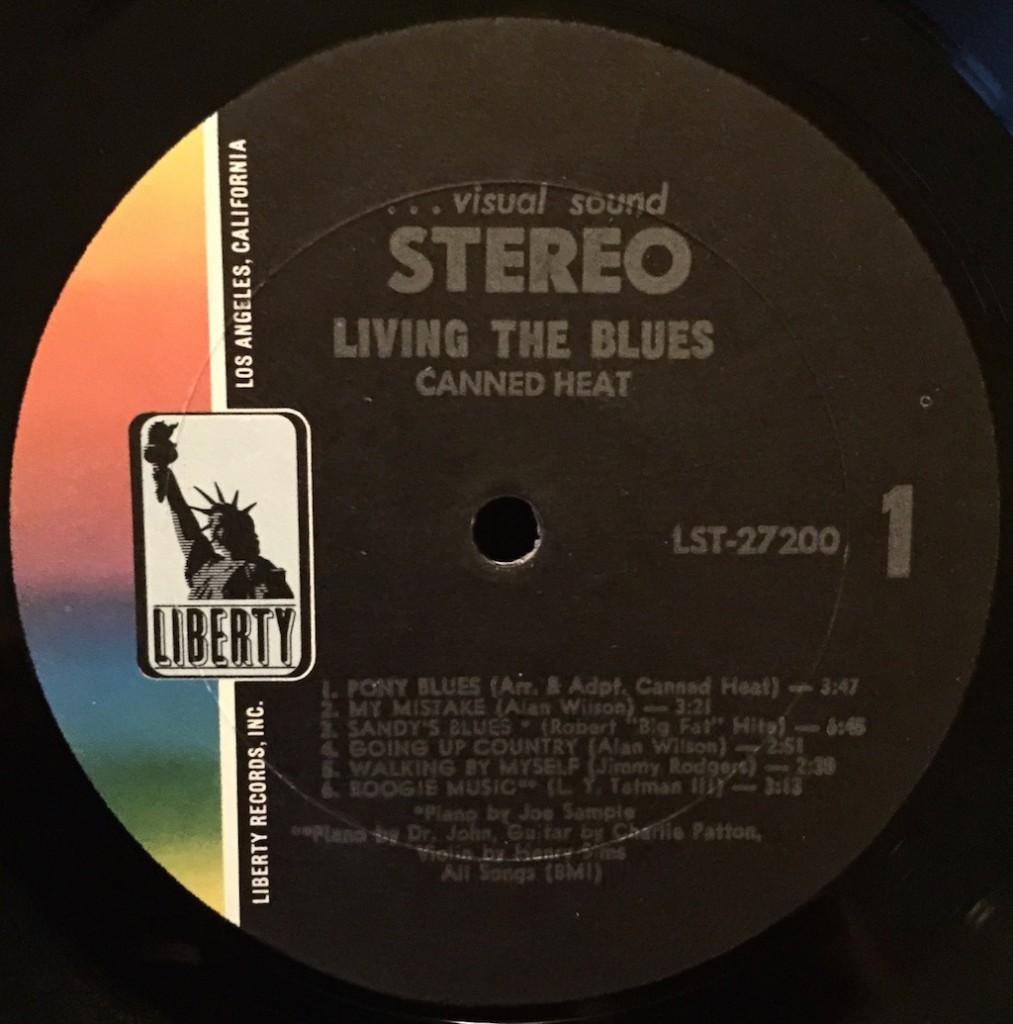

Living the Blues:

Living the Blues was released on Liberty in November 1968. The album contained their best-known song, “Going Up the Country.” “Sandy’s Blues” is a showpiece of traditional big band style jazz-blues, with blaring horns and dynamic drum riffs, accompanied by electric blues parts. “Walking By Myself” is mouth harp and old school boogie that breaks into a great harmonica solo.

Side two tells of “One Kind Favor”- the bass line is great, and sets the pace with some great psychedelic fuzz guitar fills. This album is eminently crankable- it’s nicely balanced, not too “hot” or distant sounding and surprisingly quiet (if you get a clean copy) with good dynamics and clarity. The proceedings are conveyed in a straightforward way and it helps if you turn it up. (I normally don’t listen at ear-shattering levels, but I nudged the volume control more than a couple times and never hit the “ceiling” of the record’s range).

“Parthenogenesis” reminds me of that M.C. Escher work where the figures keep morphing into something else, but the transitions all make sense- each is a logical next step even though you wouldn’t have predicted any of it at the outset. The piano part (played by none other than John Mayall) and blues lament folds into a percussion solo which morphs into a Morse code burst of guitar pulses, some edgy noodling that plays with feedback and builds to drop into an Indian motif- I’m almost ready for the sitar, when instead, I’m greeted by what sounds like Americana, only to switch to the sound of a Chicago blues bar. This track clocks in at 20 minutes, but none of it is filler.

“Refried Boogie,” at more than forty minutes, covers two full sides and demands more from the listener. It’s recorded live (“100% live” the liner notes assure us), at the Kaleidoscope in L.A. (more about the club from Skip Taylor, below). It’s probably a fair reflection of what the band sounded like live and the recording quality is impressive-in terms of both perspective and clarity.

The electric bass solo is stunning- and the backgrounds on my copy are silent enough that, apart from crowd noise, you hear little background clutter (like buzzing amps or bad mike grounds) in the quiet passages. The guitar solo that bridges sides three and four is a stinging display of electric blues virtuosity by Vestine, who alternates between an overdriven violin tone and the edge of feedback played like a Theremin. It’s one hell of a performance, particularly in contrast to the recognition given to name-brand players who don’t stay in tune or toe a melodic line.

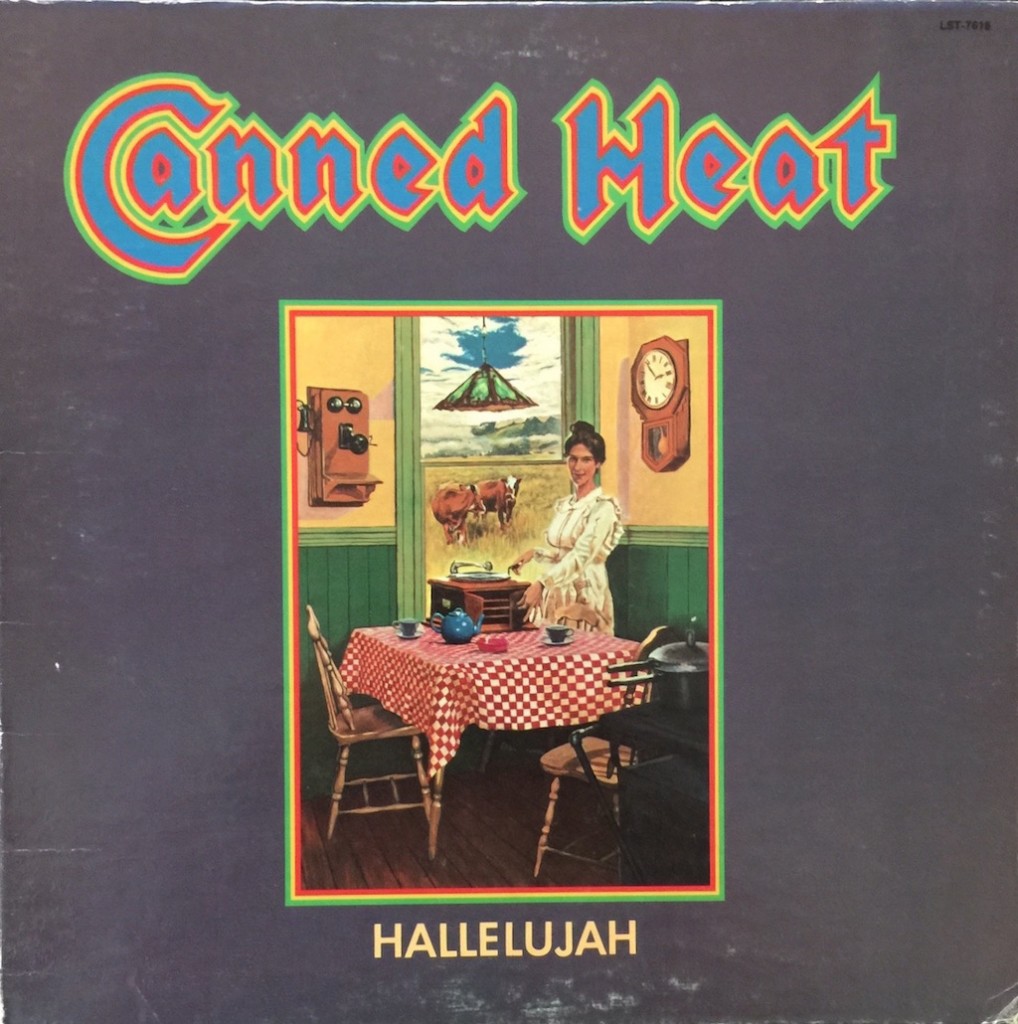

Hallelujah:

Hallelujah, released in 1969, is the last of the early albums to include Vestine.

The album jumps right in- “Same All Over” is like a traditional (read: Dixieland) style blues, but instead of horns up front and blaring, we have blues guitar, courtesy of Mr. Vestine, with some great piano work by Ernest Lane. (The back cover credits are in the form of a chart with symbols for the players- I assume the “pigs” credit is for the snorting sounds, which Skip Taylor has confirmed).

“Changed My Ways” has a Skip James-style falsetto from “Blind Owl” Wilson; “Canned Heat” is pretty straightforward blues with a very nice guitar parts shared by Wilson and Vestine. “Sic ‘Em Pigs” would have seemed dated only a couple years ago. (I’m avoiding political commentary on this site but it was part of the culture at the time). “I’m Her Man” opens with an outstanding harp intro, and after the first vocal verse, we are in very hot boogie territory- it’s fast paced, and hard to pinpoint any instrument that makes the piece- it’s all played in top form. I find “Time Was” very appealing melodically; the blues riffs fit so perfectly, this song is a classic. Larry Taylor’ bass and the guitar work of Wilson and Vestine make you want to play this one again. Side two gives us “Do Not Enter,” a hot meld of Wilson’s distinctive voice and solid blues. “Big Fat” is a shouter, a fast-paced number sung by Hite who delivers some swinging harp parts.

“Huautla” is an instrumental piece that features harp, congas and bongos that shift from blues and boogie to jazzy rhythms- the percussive elements and harp go for broke during an interlude, and when the band jumps back in, the tune sounds like you’ve known it all your life.

“Get Off My Back” is a classic blues boogie with a jazzy drum part; it’s almost like boogie rap played by jazz guys who suddenly decide they really need a psychedelic guitar solo in the middle; if you get the sense these guys are a little unpredictable, well, yeah, but their fluency of styles, and ability to deliver note perfect renditions of the parts continue to amaze. (I’m not sure I like the panning and gain riding on the guitar, but when Vestine finally opens up in earnest, it’s delivered with the man’s soul). The side finishes with “Down in the Gutter, But Free” – a slow, gospel style grinder. The organ, played by Mark Naftalin, will give you religion. Just for fun, the guitar is wielded by Larry Taylor, with Vestine playing bass. This album may be a sleeper among the others here, which had recognizable hits.

Vestine quits the band right before Woodstock and Harvey Mandel steps in. Their appearance at the festival is memorialized in the film and has always stuck in my mind for two things (apart from their superb playing): the cigarette sharing scene on stage with a fan, and the fact that the band went to the trouble to get dressed up in clean, unwrinkled T-shirts. (These guys were so far removed from what we think of as “corporate rock,” it’s almost funny).

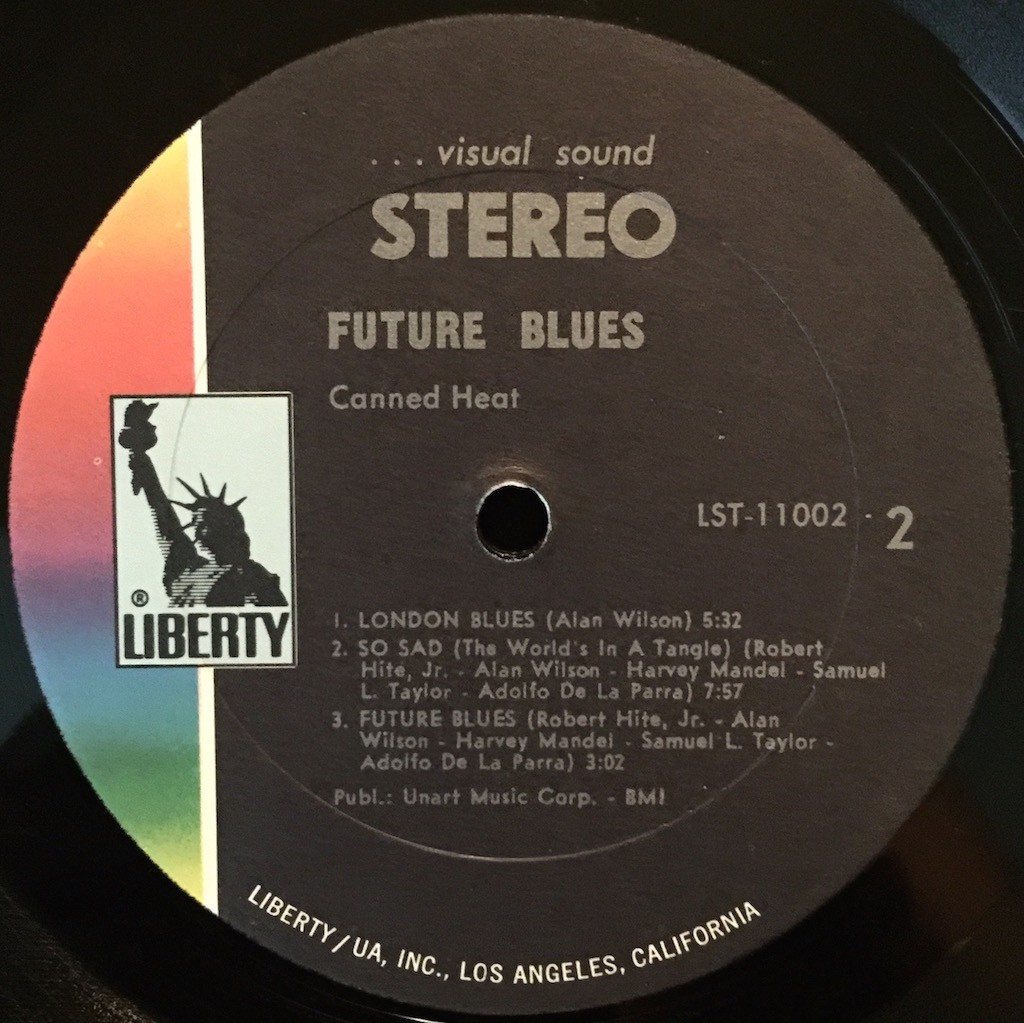

Future Blues:

The last album in this quartet of records, Future Blues, was released in 1970.

With Vestine on hiatus, Harvey Mandel delivers a rural “twang” on the first couple tracks, which sound more like a tribute to country blues despite the space-age album artwork. “That’s Alright, Mama” is played dirty and hard. Dr. John lays down some piano parts on “Skat” (the band smokes here in a more traditional jazz style). Side one concludes with that familiar anthem of ‘60s optimism, “Let’s Work Together.”

Side two gives you a more low-down Chicago blues sound, via “London Blues”- this is a fine, dark, smoky blues, with Dr. John on the 88s again. “So Sad” is a pleasure, despite the negative theme- the tricks of meter, the boogie pace and the jagged edge and slash of the guitar are a joy. “Future Blues” is a fast paced number- I guess in the future even the blues is faster—with some deft guitar work and drumming.

It’s hard to point to outstanding aspects of the playing because all of these guys are at the top of their game.

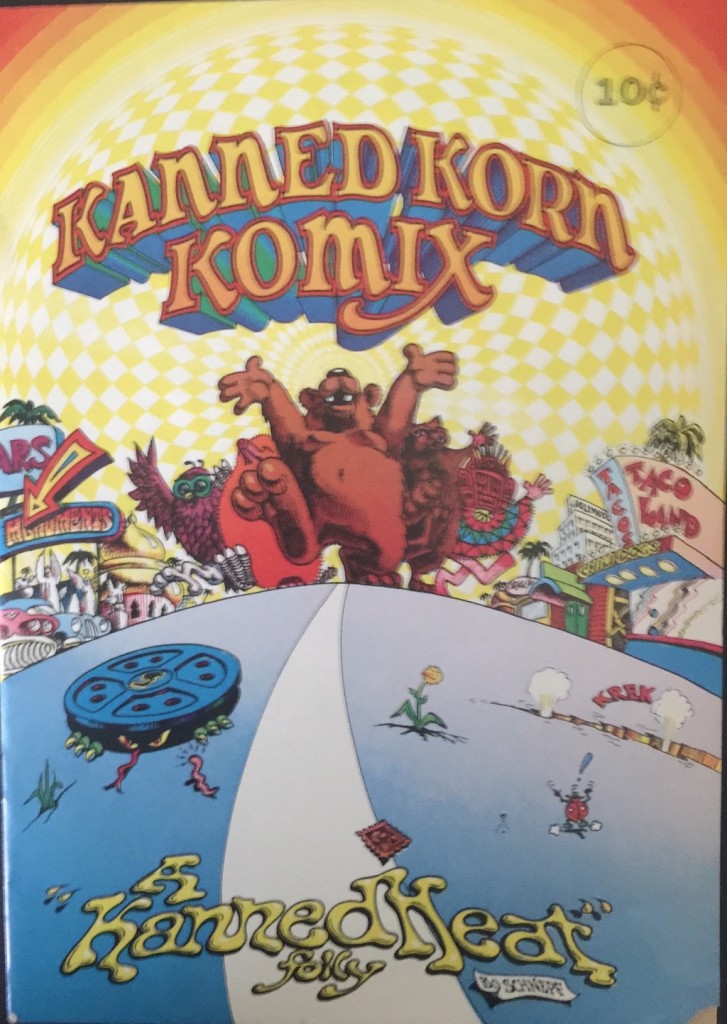

Early copies of Future Blues came with an “underground style” comic book that was so much a part of the times.

♦

This was the last of the “classic” line-up. Larry Taylor and Harvey Mandel moved on, Vestine returned, and Alan Wilson died in the fall of 1970.[4] Bob Hite survived for another eleven years. Henry Vestine, the guy allegedly thrown out of Zappa’s band for excessive drug use[5] survived them both- passing away in Paris in 1997. Drummer de la Parra is still thriving as of this writing and has toured with Mandel, Larry Taylor and others as a rebooted version of Canned Heat.

I’m sure fans of Canned Heat may have other favorites among the bands long, rich repertoire of recordings, but if I were starting out, I’d look for clean, quiet playing original pressings[6] of the four albums described above. These records haven’t reached silly prices, sound great and are a piece of music history. And though this site is really focused on vinyl, buy the Alan Wllson recording mentioned in note 3 of the Interview with Skip Taylor. It’s the least we can do.

The members of Canned Heat were blessed with gifts, but none of their lives were easy; the band had its share of tragedy over the years, but the surviving members are still out there, playing their asses off. You can check their tour schedule at the band’s site.

I was shocked to learn from Skip Taylor (see Interview) that, despite their enormous contributions to the revival and further development of blues music, the band has never received an award or recognition apart from obligatory industry awards for achieving record sales.

Related Article: Interview with Skip Taylor– which provides a first-hand account of the band’s long history, the records and their influence.

Sidebar: Rediscovering the Blues– a short overview of that era in the early-mid ’60s when avid blues fans, scholars and collectors were searching out some of the still living legends of the early blues, along with the roles played by Alan Wilson and Henry Vestine.

Bill Hart

Sept. 28, 2015

________________

[1] Some credit this festival as the real turning point in American popular music, when the bigger labels were forced to confront, and accommodate, “hippie” music as a commercial reality. The festival led to the signing of Jimi Hendrix in the States, who appeared there, as well as institutional changes at the major labels, which started hiring younger staff that “got” this new music.

[2] Liberty was started by Simon Waronker, Lenny Waronker’s father. The latter was the head of A&R for Warner Records and eventually the Warner label chief.

[3] “Boogie” was the band’s second album for Liberty. The first, eponymous album was mainly covers of old blues songs.

[4] Before his death, the band recorded Hooker ‘n Heat with John Lee Hooker.

[5] Edward Komara (see Sidebar) informed me that Vestines’ ejection from Zappa’s band was not necessarily a reflection of Vestines’ excesses; apparently, Zappa was intolerant of any drug use by band members.

[6] Note the difference in labels between the rounded boxed “Liberty” and squared box, as well as the placement and content of the label script in issues between 1969 and 1970. See Liberty Records Discography.