Those of us who have been spinning records for a while have had an interesting ride in the last few decades: first was the Death of Vinyl™ as record stores cleared out LP inventory to be replaced with racks of CDs. Many of us learned more about older records at that point, including pressings, plants and source material.

Although a few labels kept the candle lit, more and more records were being sourced from digital files; in the reissue market, a lot of those, to the extent they were even marketed in the US, sounded markedly different than their analog predecessors.

With the resurgence of vinyl came a whole new raft of labels, imprints and reissues, requiring even more diligence in selecting a decent sounding copy. You quickly learn that there are differences between recordings. I remember putting on a sax part from Gerry Rafferty and being immediately disappointed by how artificial and flat sounding the horn part was, even over a very good system.

So, much was about earlier releases, as well as those labels that kept to an “analog” source through the chain and offered well-made records without defects in manufacture. Those records cost more money to make. If you read about the travails of the Classic Records label which started in the mid-‘90s, and was absorbed into Chad Kassem’s empire in 2010, a lot of issues Hobson suffered had been addressed by record manufacturers decades earlier; much was “re-learning” what amounted to a lost art.

Some of the “usual suspects” went to higher grade vinyl compounds, fancy packaging and pricing to match—pushing the average price of the “audiophile approved” LP to above one hundred dollars US, with long lead times, limited editions and a pre-order “buzz” that played on the FOMO (“fear of missing out” for those of you who don’t keep up with Internet jargon) which in some cases drove records to sell out very fast, often within the day of release (if not pre-sold) and forced buyers into the “secondary market,”, e.g. buying from “flippers” who mark up the price considerably.

Gearbox Records, located in London and Tokyo, has taken the best of the lost art of making records and managed to avoid many of the pitfalls that make buying new, high-quality records a less than joyful experience. It only dawned on me recently that quite a few records I have picked up in the last few years bore the Gearbox Records label. This independent label has its own analog mastering studio and releases older and new records that are top tier in quality, drawing from a diverse roster of talent, and charges a reasonable price for a very high-quality slab of vinyl.

The Gearbox label was founded by Darrel Sheinman in 2009. Sheinman, a musician and audio hobbyist, benefitted from his knowledge of the audiophile market and his considerable collection of older jazz records to tap into something special; in a sense, every record released by Gearbox is a premium offering and reflects Sheinman’s passion for the music and performance. Along the way, the company has expanded and embraced digital as well as analog releases. It may be a model for what the best independent labels can offer. (For me, Island remains one of the high-water marks given the range, quality and cultural significance of its catalog, especially during the “pink label”/”rim” era).

I had an opportunity to talk with Sheinman about the company, its history, growth and his perspective on the market.

TVP: I don’t know how many labels start with great ambitions and simply fold after a few releases, but yours is the exception. Why is that?

DS: We were well funded. It is difficult to deal with negative cash flow that a label brings. It takes a while to recoup and the label has to front the funds. Labels are really financial institutions in a creative world. They swap a cash asset for copyright asset and reflect the ultimate patient capital.

TVP: You started at a time when the vinyl revival hadn’t quite taken hold. What was 2009 like for you? I don’t remember it as an especially good time to “invest” in a record label making analog records but could be wrong (and in the long run, probably am).

DS: At that time I was running the label as a hobby, so was less concerned about income. All I wanted was to see great hidden music gems available on the best musical source.

TVP: Is it fair to say you were an audiophile before you started Gearbox? Tell us your perspective on that because sonics are important. Leaving aside what one might consider audiophile banalities—good sonics but unadventurous music/performance, the improved sonics of a good recording/mastering yields more involvement in the music.

DS: Good sonics means hearing more of the music. Naturally therefore, one becomes more involved. However, sonics starts well before the audiophile’s playback system. It comes from the recording, mix and mastering. If they are no good, then you can have the best playback system in the world and it will still sound awful.

TVP: Tell us a little about your studio and how you go about shepherding a release through the process. In this context, let’s assume the reader is not intimately familiar how a record gets made and the choices that can and inevitably do get made along the way.

DS: Sometimes I will studio produce a record at a great recording studio. I like this because I am more intimately involved with the desires of the musicians and I tend to direct the tracking to remain in the analogue domain wherever possible. Other times, we receive the final recording and go on to master it for vinyl, digital and CD. Our mastering process has certain rigours too. For example, we will not upsample digital without going through tape first. Also we will only cut a vinyl lacquer master from tape of digital resolution of of 96k/24 bit or higher, and we only use digital when we have to (eg where restoration of the source is required).

TVP: I can’t tell you how many major label offices I’ve been to during my career as a lawyer—almost none had a decent playback system in the offices. You are a bit different. Readers will be interested to learn about the systems you use in the studio.

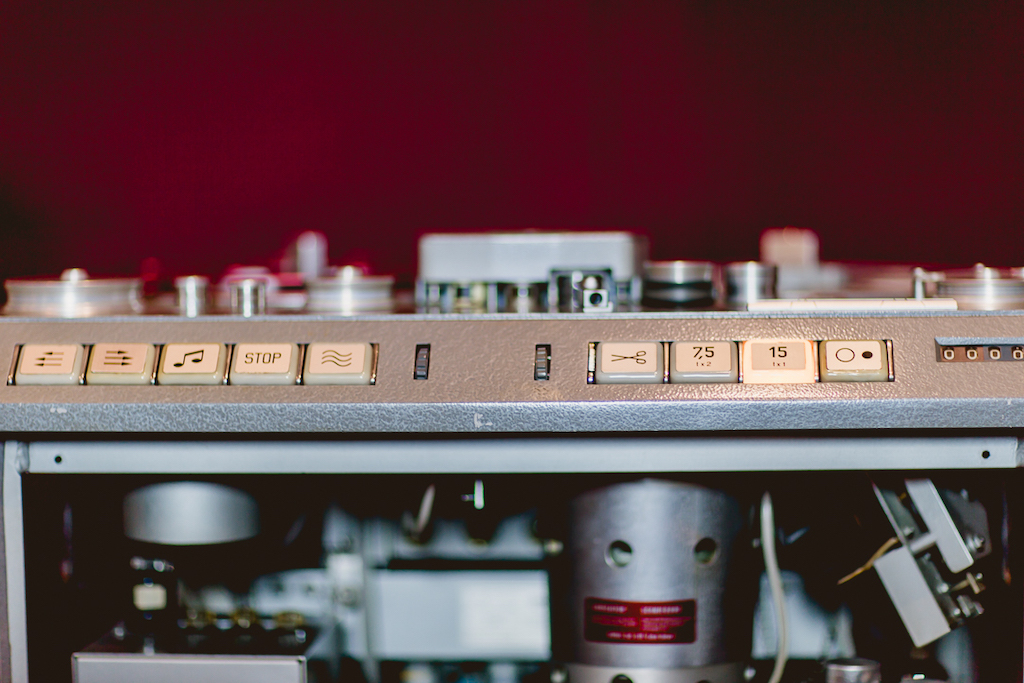

DS: I think majors are becoming better now and are realizing that to be credible they must be able to analyze music not just market it. We use Audio Note 211 tube amplifiers for monitoring and we have a selection of turntables from a mid-range Rega, a vintage EMT and an Audio Note AN2. We use vintage Western Electric cutting amps and have 5 different reel to reel machines and cassette players, namely vintage tube Studer, Philips and Nakamichi.

TVP: You have issued new records along with reissues. Are you the ultimate decision maker in terms of what gets released? And what criteria do you use?

DS: Our “reissues” are actually previously unreleased gems rather than true reissues. Yes, I do all the A&R but of course value the input of my team, wife, children etc.! A&R is so subjective. One cannot rule by committee on this. All my mistakes are my own.

TVP: Who at Gearbox does the actual mastering and cutting?

DS: I used to do it, but found I could not run the business as well. We have had various assistant engineers, but for the last 6 years we have had Caspar Sutton-Jones working his magic. We offer our services to 3rd parties too, which Caspar handles. I now only get involved in our own proprietary releases and cut from time to time to keep my eye in. I enjoy it.

TVP: Do you typically use one pressing plant? There are diverging views on which plants make the most consistently good records. In my view, it has more to do with the label’s willingness to exercise quality control than any inherent “magic dust” at one plant over another.

DS: We use Optimal in Germany for all of our standard releases. We also use Toyo in Japan for our OBI Japanese editions. And you are right, the label is key in making sure this works well.

TVP: Among new artists you have signed Jelly Cleaver, whose “Forever Presence” EP is stunning. How did you get onto her?

DS: She came to us via a manager who handled Sarathy Korwar. Glad you like!

TVP: And among reissues, you’ve made some interesting choices, from Kenny Wheeler’s Windmill Tilter to Mellow Candle’s “Swaddling Songs.” Peppered among these less well-known records are household names like Buddy Rich and Thelonious Monk. Is there any consistent theme here among these choices?

DS: Not really. The music simply has to be good. The two reissues you mention are actually 3rd party work we did for Decca.

TVP: You get to hear the tape in a studio with topflight gear. And you listen to test pressings to approve one for release. How close are the records to the tape, on average?

DS: As close as we can get. I would say there is little difference between our finest cuts and the master tape by the time we have finished with it. The playback system will probably have more effect on the sound at this stage.

Readers: Keep an eye on this label. They make high quality, musically interesting records, and are willing to take risks rather than just reissuing the same old audiophile warhorses. And they aren’t crazy money either.

All photos-Gabriel Bertogg

Courtesy of Gearbox Records

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.