The following interview with Glenn Berger ties into the release of his new book about working at the legendary A&R Studios in New York City during the golden age of the studio. Readers are encouraged to first read the accompanying review of Berger’s book, “Never Say No To a Rock Star In the Studio with Dylan, Sinatra, Jagger and More.

Glenn Berger, after he had moved on from A & R Studios

You got the job at A&R Studios when you were 17 years old. Did you have any sense of the caliber of artists and production work going on there when you started?

GB: Oh, yeah. The studio manager was talking about Bacharach and McCartney the day I walked in to start my job. My fantasy was that I was going to be busy making effects and doing tricks with the equipment. It turned out that my job was to facilitate the artist’s creativity- we had to get out of the way- it wasn’t about the recording process as a technical thing (though we had to have that right), it was to capture and not interfere with the artist’s process- in a sense, we had to be invisible.

You had some modest engineering background before you arrived at A & R?

GB: I bought an Ampex recorder when I was 14 or 15 and got pretty good at overdubbing. I also had an internship at a jingle house- the biggest in NYC at the time. But when I got to A & R, I was interviewed by the monster engineer, Don Hahn, who asked me what I could do. I said I could run a tape machine. “But do you know how to do it to A& R standards?” It was pretty clear that the studio had a level of quality that I had to meet, and that’s where the real learning began.

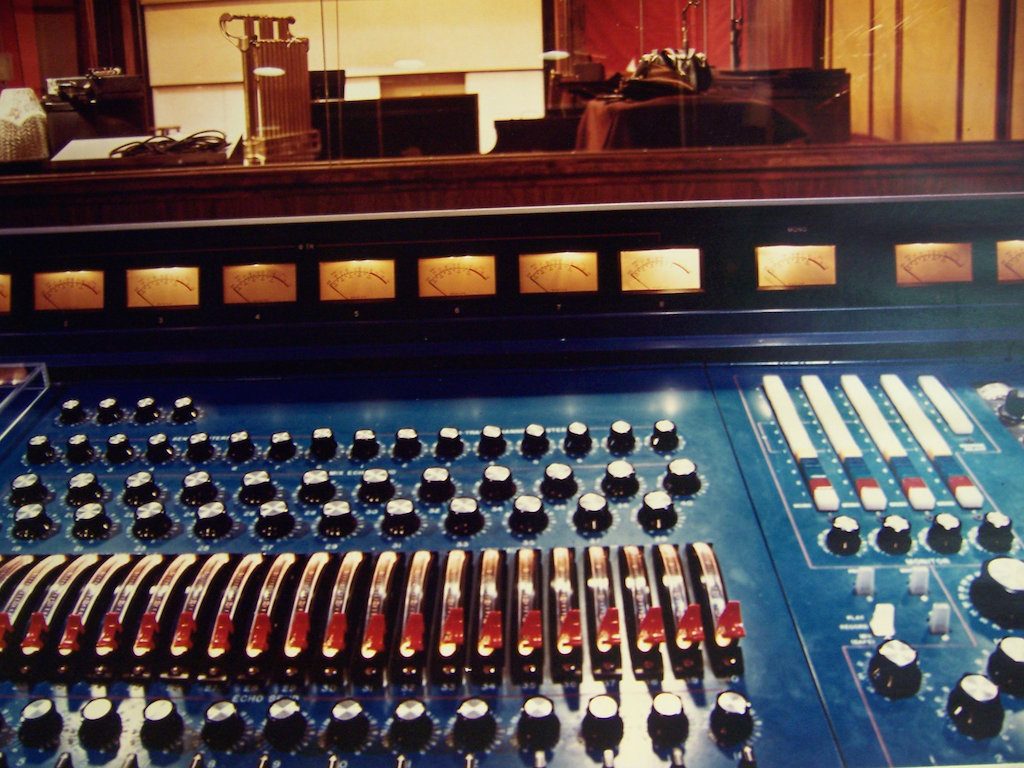

Suburban Sound console

You describe pretty effectively in your book the relationship between the work of the artists and the engineers. It seems like the most difficult task for technical and engineering folks was dealing with the unexpected- whether it was an artist’s change in direction, an equipment glitch or something else—

GB: When I train people, the first thing I tell them is “get paid.” The second is “to expect the curve ball.” Murphy’s law applies with a vengeance in this field. Ironically, I just gave a paper at a conference and the A/V system crashed. I reminded myself that I didn’t say a prayer to the equipment gods.

Some artists were really using the studio to compose, right? They may have had a rough idea of the song, but needed to work out how it sounded with additional instruments.

GB: Studio time was $200 an hour then (basic rate), and the session guys had to be paid; if you went over time a minute, the rate went up. So, with large sessions, that got costly real fast. Artists like Paul Simon could afford it; I believe he paid for his own recordings- and he was such a perfectionist, he didn’t worry about the time or cost. He agonized over his songs. But when it was time to record the orchestral interlude for “Still Crazy After All These Years,” Simon didn’t have the section written. He went into another room and composed it while the room full of players and the arranger waited. There was a lot of money floating around at the time. Simon would say to me: “I’m going out to dinner with some friends and I’d like to bring them back to the studio later for them to hear some tracks. So hang around.” So, I and the studio got paid to sit there. And he never showed. I’d wait ‘til midnight and then check out. Sinatra, on the other hand, was so used to recording with a full orchestra live, he’d able to get it done in one or two takes. He came from an era when there was no overdubbing.

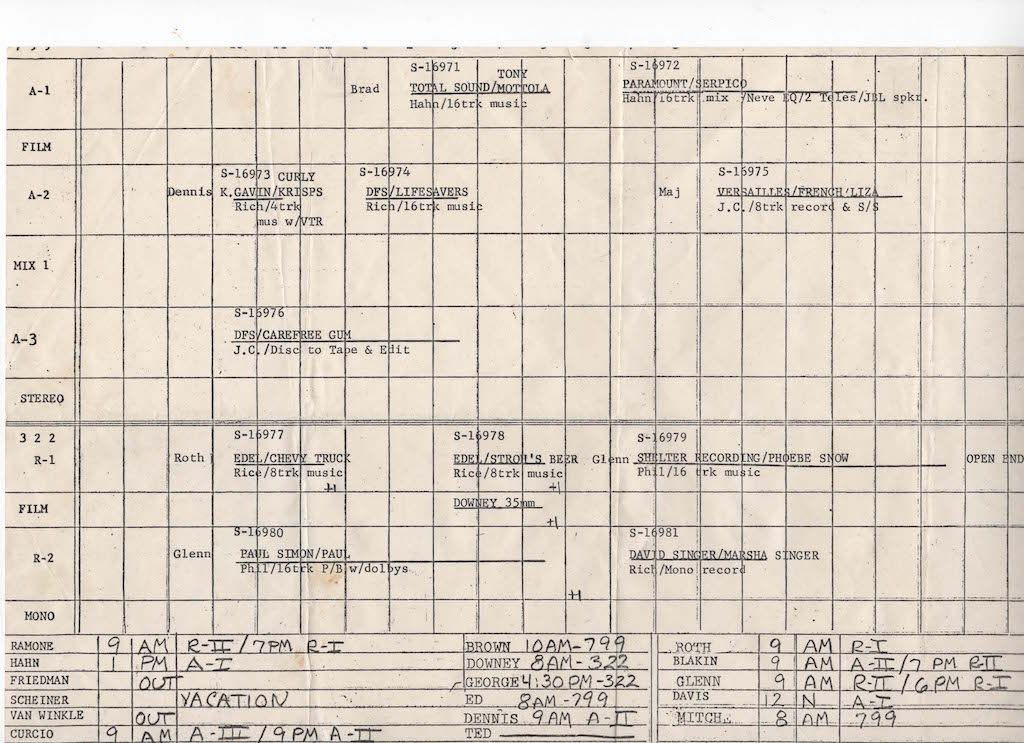

Studio booking schedule at A&R

Were there “standard” tricks you employed in microphone set-up or other preparation for the recording?

GB: One thing we would do if we were working with a new artist was to set up several microphones, so we would select the “right” mic for that person. We’d put a piece of tape on that mic with the artist’s name as the “one” for that singer – keep in mind that each mic, even of the same type, like a AKG 414, sounded different – each had a somewhat unique character.

We also tried to be triply prepared- we wanted to be completely relaxed by the time the artist arrived- not scurrying around doing set up. An artist sees that kind of energy going on, and it makes them anxious.

In one session with Paul Anka—who would start working at midnight— despite all my preparation, his headphones didn’t work. I’m sweating bullets – and he’s pissed, saying the name of all his hits into the mic while I’m trying to make the thing work! At the end of the session, he opened his briefcase, and gave me a hundred from a stack in there. I won’t tell you what else was in that case!

Studio A-1 at A&R Studios

At the time you started at A&R, they already had big multi-track consoles and tape machines. How many tracks and what consoles were used?

GB: When I started, we were doing 16 track and later moved to 24 tracks. The consoles were pretty much custom made. (There weren’t that many manufacturers- Neve were around, but quite expensive). So each console sounded different. You can hear it on the records made then. On the early boards it was a clean, simple chain from microphone to tape machine. It sounded sweet and fat. On the console in our big room, A-1, that we called the “flying ‘v’ my mentor, Phil Ramone, had them put knobs in the shape of hearts, clubs, spades and diamonds. We also had a few Suburban Sound consoles (see the interview with Brooks Arthur, a partner in A&R who describes the board in some detail) and even an old Neumann, that had the build quality of an old Mercedes.

The Neumann Console

For tape, we had an Ampex MM-1000 16 track and a 3M machine that had a very interesting transport- with what was called an “iso-loop” capstan system. We also had a lot of Ampex and Scully two tracks. Eventually, we bought Studers (both two track and multi-track). In those days, A&R had a cutting lathe so we could cut acetates to see how the recording sounded.[1]

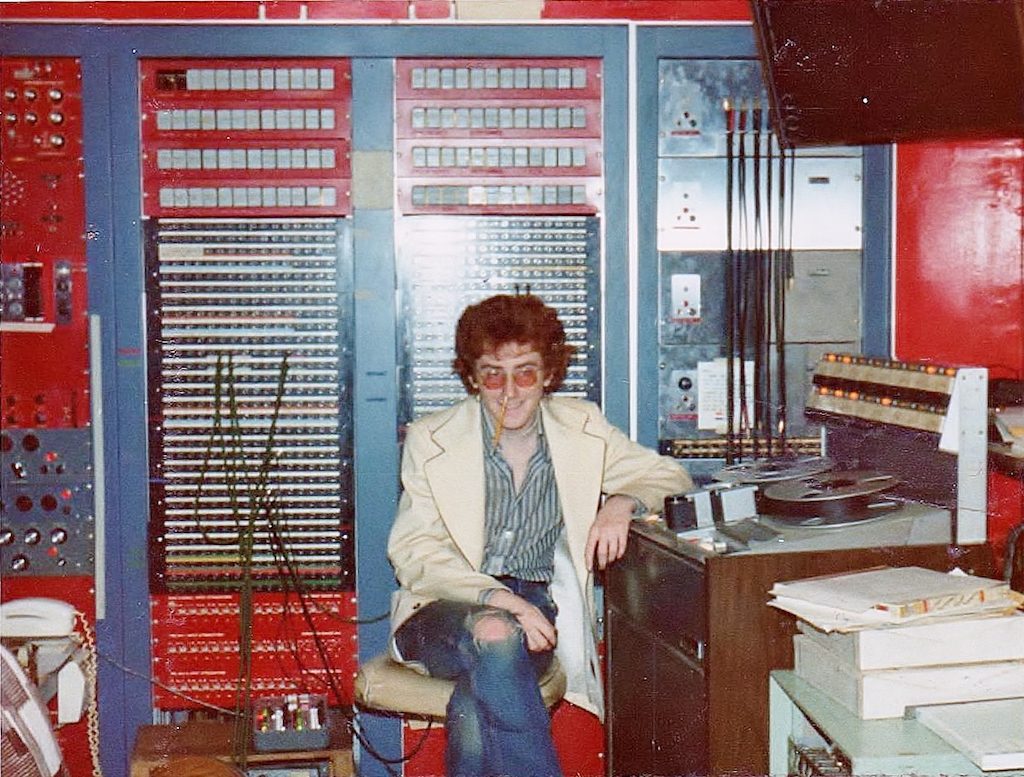

Glenn Berger at A&R Studios in 1974

I don’t know if you are aware of the resurgence of tape in “high-end” audio circles- 15 ips 2 track using refurbished machines- either semi-pro or pro, often with outboard preamps.

GB: I know there is a romantic aspect to analog- tape, tubes, etc.- but working with that equipment as tools, it was a giant pain in the ass. Whenever I heard what was cut to the record, it was always a disappointment. The tapes obviously were better sounding. Phil [Ramone] knew how to get good sound for the medium of vinyl in the day.

You made a statement in your book that, to me, is telling: “What came as a revelation was when I came to understand just how much artifice was required to make something sound ‘real’.”

GB: I think this is true of all art. I learned this (or re-learned it) working on the soundtrack to Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz. We’d spend a day making sure the throw-up sound effect was convincing. On records, the trick was to get the overdubs not to sound like overdubs.

The seventies were really a golden age of the recording studio. A lot of money and attention was focused on the gear and the rooms—as the money flowed and equipment became less primitive and more sophisticated. Was there ever any attempt to capture the room acoustic and not to change what was coming from the mics?

GB: I think that era was both earlier and later in pop. When Phil recorded “Girl from Ipanema,” he did it by just throwing up a few mics. In the ‘70s, I think the mindset was, we had all this equipment – why not use it? Everything was recorded in isolation, separately miked, no bleed through, no “room” acoustic. Jazz and classical excepted, of course. Steely Dan were different – they tried to get the sound from the instrument and only used EQ as a last resort.

Glenn Berger with Solomon Burke

One thing that struck me in reading about the sessions you worked on, and the grueling pace, is that you never lost the desire to understand what makes the “magic” in recorded music.

GB: Music (and art in general) is such a mysterious thing to me. I think about it on a couple of levels – there is something ineffable about great music, but it is so simple it eludes me. You know it when you hear it. With Phil, there was also an ability to make magic happen. Somehow, he was always in the right place at the right time. People focus too much on technical perfection. It’s the “feel” that counts.

You now practice as a psychotherapist and told me you just returned from a conference out West on “Creativity and Madness.” Looking back on your experience in the music business- working on some of the biggest artists at the time in in what was considered one of the best studios in the world- what insight can you share about the creative process?

GB: Courage and endurance- it isn’t easy to produce art. The hang up for most artists- for most engineers, producers, really for everybody as a human being– is the fear of being humiliated. It takes a tremendous amount of courage to put yourself out there- Bob Fosse, Phil Ramone- those guys were at the top of their fields, yet were terrified of screwing up. So they worked their asses off, they endured any pain, to get it right. And despite their terror, they put it out in the world. That’s what courage is. The creativity didn’t come from flights of genius – it came from perseverance.

Glenn Berger today

There was also a bittersweet quality to reading about some of this—not that you were melodramatic about any of it, but it really was a lost era- the only thing left, for the most part, is the recordings themselves. The industry has changed, some of the greats- like Phil [Ramone], have passed and there are far fewer major recording studios and labels willing to fund big recording projects.

GB: I don’t think it is a nostalgia trip. I listen to a lot of contemporary pop- I have two kids, and a lot of it is good, but very little of it is great. The technology makes it possible to have a standard production quality. So, we don’t have the extremes—of really bad stuff, and great stuff, as we did in, say the ‘60s. Certainly, the era of great studios with an army of session people, arrangers, producers, songwriters –everybody in the same place at the same time- doesn’t really exist anymore. It was an extraordinary time. People can literally “dial it in” today, by recording their part(s) remotely. The energy of the bigger recordings with all the musicians in the room is missing. So much happened in small studios located all over the world – we were all a part of this incredible community – whether it was Muscle Shoals, Los Angeles, New York or London, and we cross-fertilized. We competed to be the best, to make the next amazing hit, and everyone was listening. We all shared a standard of excellence. That’s what I learned and that’s the way I try to live my life, even though that world is gone.

♦

Bill Hart

August, 2016

__________________________________________________________________

[1] This is how those Dylan bootlegs of the NY sessions got out- from a reference acetate.

Photo credits:

Image of Glenn Berger by the tape machine by Joshua Silk at MSR Studios.

Suburban Sound console photo by David Greene.

A&R Schedule by Larry Franke.

Neumann console photo by Bernie Drayton.

Glenn Berger (with pencil in nose) by Brad Davis at A&R Studios, 1974

Solomon Burke and Glenn Berger by Glenn Berger.

Glenn Berger head shot by Jeremy Folmer.

All photos by permission of Glenn Berger.

A big thank you to Glenn Berger for writing a book full of insight into the creative process during the heyday of the recording studio. My additional thanks to Glenn for this interview–Glenn is full of energy and ideas. He still has that refreshing sense of candor and a little awe that makes the telling of his story– as a young engineer working in one of the greatest recording studios of all time–a fascinating read. Glenn’s blog has a section devoted to his book, and you can buy a copy online through the links he provides there.