Mark Weber on the West Coast Experimental Jazz Scene and the Shape of Things to Come

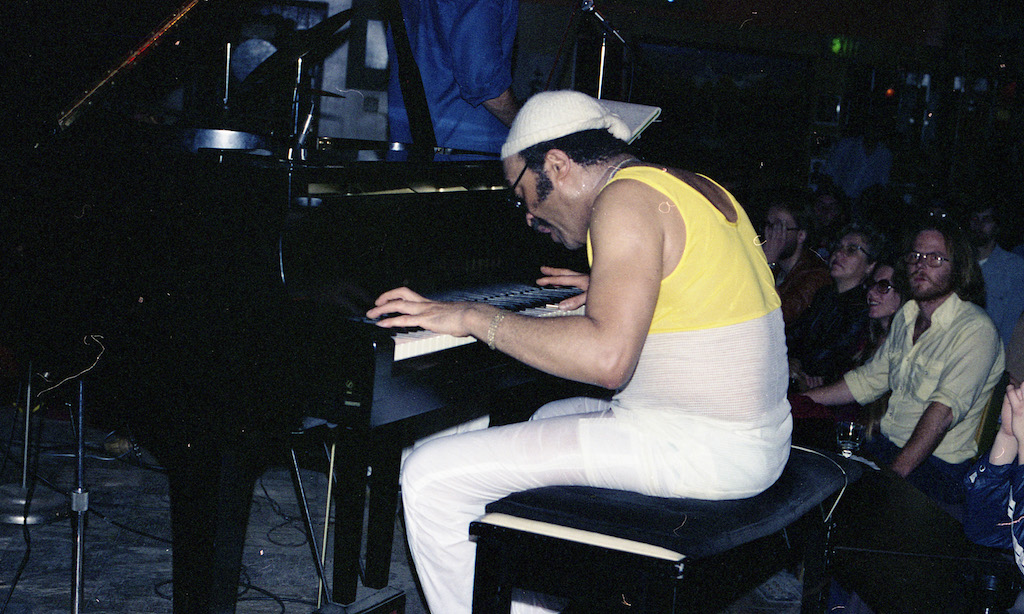

Sun Ra Arkestra – April 2, 1981 Los Angeles – photo by Mark Weber

Sun Ra Arkestra – April 2, 1981 Los Angeles – photo by Mark Weber

I first got onto Mark Weber when I was researching Horace Tapscott and landed on Mark’s webpage, which included a photo essay of the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra.

Mark spent the first 32 years of his life in LA, and was the CODA jazz magazine LA columnist for the better part of a decade, spending a total of 18 years reporting for CODA from Cleveland, New Orleans, San Francisco, New York, Detroit and Salt Lake City. His archive of photos and essays from the period 1970 through 2005 is now lodged in the UCLA Special Collections. Mark moved to Albuquerque, NM in 1991 and hosts a jazz radio show on KUNM.

I thought it would be fascinating to tap into Mark’s considerable knowledge and experience during what was a vital era of experimental jazz that set the stage for the shape of jazz after the ‘60s.

TVP: You are quoted on the UCLA Collections page:

It would be a major disservice to a great art form to contain it within a defined orthodoxy. Without a definition it radiates outward. Nor would I care to venture a speculation as to what jazz is. I’m not too locked in on the word “jazz” anyway. If a cat (or kitty) can play, then he can play. Jazz is not a type of music, it is not a specific form or category. Jazz is a manner in which music is played. Jazz is the way you play the music, not the music that is played. Jazz is the original Free Form. It continues to evolve.

That’s a pretty astute observation. But the “way the music is played” is riddled with conventions isn’t it? And the music and the players you gravitated toward seemed to defy those conventions, didn’t they?

Mark Weber (MW): There was something about the Sixties that made us all want something new — like Ezra Pound always said “make it new” —- So, yes, I came into the music backwards —- I jumped head first into the avant-garde and worked my way back to the beginnings —- It helped that the earliest jazz critical writings I was into were those of Martin Williams, who was a guy who dug Cecil Taylor but also the old New Orleans styles (although he sure dumped on George Lewis, the clarinet player, referring to him as an unsophisticated primitive who had been promoted by the Dixieland surge of the 1940s)(I like George Lewis)(and I like the other George Lewis! The trombone player) —- AND so, nowadays, I’m a big fan of standards and the Song Book, I just think to hear a standard puts us all on the same footing (a lingua franca) and great fun to hear where the improviser abstracts and departs.

Cecil Taylor at The Lighthouse, Hermosa Beach, California – June 7, 1979 – photo by Mark Weber

TVP: How did you get into this scene originally? What attracted you? And why did you stay with it?

MW: I grew up musically in the 1960s transistor radio era and that’s more or less where I started, but, even before that my family had Tchaikovsky and Mozart (my folks had maybe ten records and that was it)————Crazy as it sounds but one of their records was a single LP version of the 1961 Louis Armstrong – Duke Ellington session which is still one of the top ten most important records you should wrap your ears around. So, I ran out of rock & roll. Rock was only ten years old in the 60s and there just wasn’t enough of it. And well, I attribute my ventures into jazz & blues to the Sixties generation —- that era was all about expanding your consciousness, right? And even though I’m a white guy raised in the white suburbs of Southern California, I made the leap into Black cultural music, most simply because I loved solos, and I suppose subliminally I was attracted to the harmonic density and rhythmic layering. I stuck with it because I probably have the music gene.

Fostina Dixon and her group Collage – July 11, 1981 Watts Towers Jazz Festival – photo by Mark Weber

TVP: This thing called “spiritual jazz” really reawakened my interest in jazz because it felt more gritty, mixed with funk and cosmic stuff, it really took the style of jazz from the club scene into the streets and captured the changes in black urban culture in the post-‘60s. How would you describe it?

MW: I guess we could call Albert Ayler spiritual? And who can deny him? Mostly, I think of Alice Coltrane when I purely think of spiritual jazz, and I used to be nuts about her records. I’m not sure how to answer this question. Obviously, the Black American church is one of the ingredients in jazz. I suppose when a musician/artist masters their craft & instrument, and can “play” in the purest sense, there’s something deeply unusual about that, as it connects with pre-rational thought, and just pours out. That gets to you on deeper levels of humanity.

TVP: Given your travels, and the time you’ve spent in New York, Detroit and other places, apart from LA, are there any distinct regional “fingerprints” to the sound of, say the New York or Detroit scenes, compared to the LA scene?

MW: There most certainly are differences. When we moved to Albuquerque (1991) I thought I stepped into a time warp. The jazz scene here was still playing the Song Book, which, by the 70s out in Los Angeles wasn’t really looked at that much (see the albums made back then, everybody felt compelled to be original and write tunes). In general, I’d say 1950s West Coast delved deeper into a relaxed and contrapuntal approach than what was happening in NYC. West Coast jazz has gotten a bad rap over the years and that’s because 95% of the jazz historiography has been written by East Coast historians, and for whatever reason they thought the music out on the Coast was limp. We have a guy who lives here in New Mexico, who’s from NY, and he seems to think all jazz should be rough & tough & in-your-face, and that what was going on in LA not worth investigating. But, thanks to labels like Fresh Sound and VSOP/Mode and Lonehill, all that is being re-issued, and to great acclaim. For the last 25 years I’m “bi-coastal” and visit both LA and NYC often, and the one thing I notice nowadays is that LA has almost zero audience for this music (I think the crowded freeways to blame). Out here in Albuquerque I’m often the youngest person in the audience and I’m 65! But, out in NYC the audiences tend toward the 20s & 30s & 40s with a few old codgers thrown in for good measure! (If I were younger I’d move out to Brooklyn and document the jazz scene that has been on-going there these past 20 years —- a whole new chapter in the history).

Recording session w/ Ratzo B Harris & Mark Weber – bass & poetry – November 19, 2018 NYC – photo by Francesca (courtesy Mark Weber)

Recording session w/ Ratzo B Harris & Mark Weber – bass & poetry – November 19, 2018 NYC – photo by Francesca (courtesy Mark Weber)

TVP: Some writers and scholars attribute the growth of “spiritual jazz” to the awakening of the black community in the late ‘60s and the change in the popular music market—where more conventional jazz sounds simply were not selling and artists turned inward, to their communities and less “produced” recordings, a lot of which were released on small or private labels. Can you lend any perspective to this change?

Bobby Bradford & Glenn Ferris – April 1, 1979 —- photo by Mark Weber

Bobby Bradford & Glenn Ferris – April 1, 1979 —- photo by Mark Weber

MW: Make no mistake, those artists would have loved to be on a major label and making a living selling their records. It’s just that the steamroller of the rock industry completely smothered everything else. And then in the 1970s along comes Disco and also Reggae, and jazz really went into decline. Jazz has always been a subculture, anyway, but in the 1970s it was very weird out there. I’m still wondering how we survived it. But artists being artists they learned how to make records themselves and documented their on-going work. That’s how it was with artists that I knew. They certainly would have loved an established record company to do all that for them but that was not forthcoming. Many jazz folk looked to Europe in those years.

Tim Berne (alto) and an LA group he called Vat : Glenn Ferris(trombone), Vinny Golia(baritone), Roberto Miranda(bass), Alex Cline(drums) – October 28, 1979 – photo by Mark Weber

Tim Berne (alto) and an LA group he called Vat : Glenn Ferris(trombone), Vinny Golia(baritone), Roberto Miranda(bass), Alex Cline(drums) – October 28, 1979 – photo by Mark Weber

TVP: We’ve looked at some releases from Strata-East, Tribe and Nimbus West on TheVinylPress. All of them shared a sort of interchangeable ensemble of players, a handful of studios and what seems to be a fair amount of cross-pollination. Was that part of the magic? The small-ish community of players who performed with each other regularly, outside of the studio?

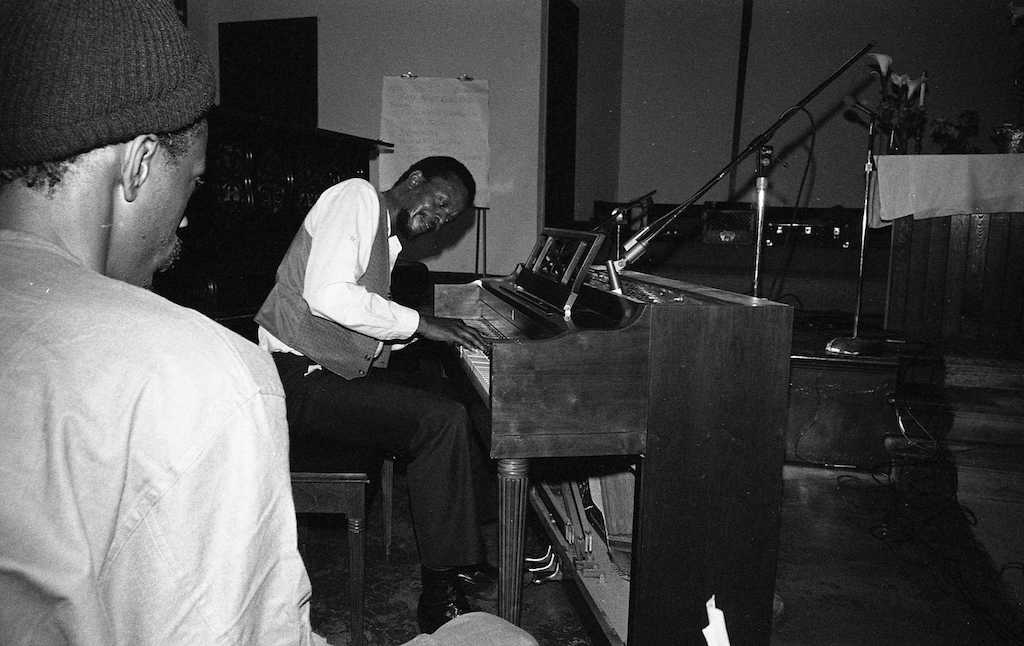

MW: Jazz players share a common language and methodology and even a certain decorum. I’ll say this, to my ears, the most successful ensemble music is that which is made by artists who have played together often, rather than say ad hoc get-togethers and “pick-up bands.”  Horace Tapscott (while singer JuJeGr looks on) – April 26, 1981 – photo by Mark Weber

Horace Tapscott (while singer JuJeGr looks on) – April 26, 1981 – photo by Mark Weber

TVP: Tapscott was performing for a while before he was recorded by Tom Albach. How did Albach get plugged into this scene?

MW: Tom Albach came out of WWII and settled in LA and says that LA really had a great feel back then. He and Tapscott were a perfect fit, as they both are overtly political. And we all need to thank Tom for documenting Horace, as it would be hard to fathom if all of that got away from us. Horace was on very few records prior to his association with Nimbus West in 1978.

TVP: Are there other labels, apart from Tribe, Strata-East and Nimbus West whose records are of interest? (Black Jazz for instance?)

MW: Nine Winds Records will go down in history as a major documentation of late 20th century LA music. And out in NYC don’t forget New Artists Records, which started out vinyl and then transitioned into CDs, same as Nine Winds.Cecil Taylor self-released on vinyl two albums in the mid-70s: INDENT and SPRING OF TWO BLUE JAYS. Both, monumental. And then there’s Carla Bley’s Watt label. There are of course many one-shot deal record companies that only put out one album and really didn’t go much beyond that. Like John Carter’s ECHOES FROM RUDOLPHS. I wrote an essay at my website on the Early LPs of the Free Jazz scene in LA.

TVP: Among the various recordings, are there any that you’d identify to readers as “essential” and within that, good introductions to the musical style that are accessible to someone who is interested in exploring some of these sounds?

MW: Lester Young, Charlie Parker, Lennie Tristano, Louis Armstrong. For Lester get the Keynote Recordings of 1943, essential. A lot of stuff traces back to Lester Young. We’re in a unique place in time right now, where we can look back with a certain objectivity. (Although, it can be hard to figure who did what first and who developed out of someone else, you have to hit the history books for that.) I do wish I had a time machine. I’d love to go back to the 1920s and 30s. I think as the dust settles on the 1960s/1970s Free Jazz Era listeners are going to find trumpeter Bobby Bradford to have been a major artist. He’s an example of a thinking player. (I told him years ago that I feel like I’m listening to three-dimensional chess when I follow his solo improvisations.) My favorite Horace Tapscott album is AT THE CROSSROADS in duet with drummer Everett Brown Jr. But, all of them are good. As for Cecil Taylor I’m old school and love his early recordings where he was still playing tunes. And the apex of Albert Ayler is the album SPIRITUAL UNITY (1964) and I don’t say that lightly: last year I did a radio show on Ayler and gave a serious listening to all those albums, having had them in my collection since the 70s, and SPIRTUAL UNITY is the one. I also highly recommend Connie Crothers first album PRECEPTION (so much of where she went with her career is presaged in that album) and also all of her quartet records. Another band I like a lot is M’BOOM. On and on . . . .

TVP: Your material, now archived at ULCA, is considerable: more than 14 linear feet, including 36 boxes. Has an exhibition of your photographs been mounted?

MW: Wow, 14 feet? This is the first I’ve heard that figure, haha. I arranged for them to have 10,000 photos, most of which are silver gelatin prints, and also many slides —- blues & jazz artists, photos I took in the 70s & 80s in Los Angeles. That transaction happened in 2005. I still send them annually my radio interviews and much of my digital photos on disk.

TVP: Any other thoughts you can share with readers, given the limits of time and space?

MW: When people ask me how to listen to jazz, I tell them to listen to the first note and remember it as everything else relates to it. The other lesson I suggest is that next time you’re at a concert to listen to at least 2 tunes with your eyes closed —- (This eliminates that phenomenon of listening with your eyes) —- the other trick, when you’re learning how to hear this stuff, is to pick one instrument in the ensemble and focus totally on what that instrument is doing and how that instrument is working within the ensemble, pretend you are that instrument —- Let me know how it goes . . . . .

Readers should follow Mark at his website:

https://markweber.free-jazz.net

Mark’s show is on http://kunm.org/ at 12:06 Noon on Thursdays for 90 minutes, Mountain Standard Time.

My thanks to Mark Weber for his insight and time in putting these thoughts together, as well as for the wonderful images.

Bill Hart

Austin, TX

December, 2018

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.