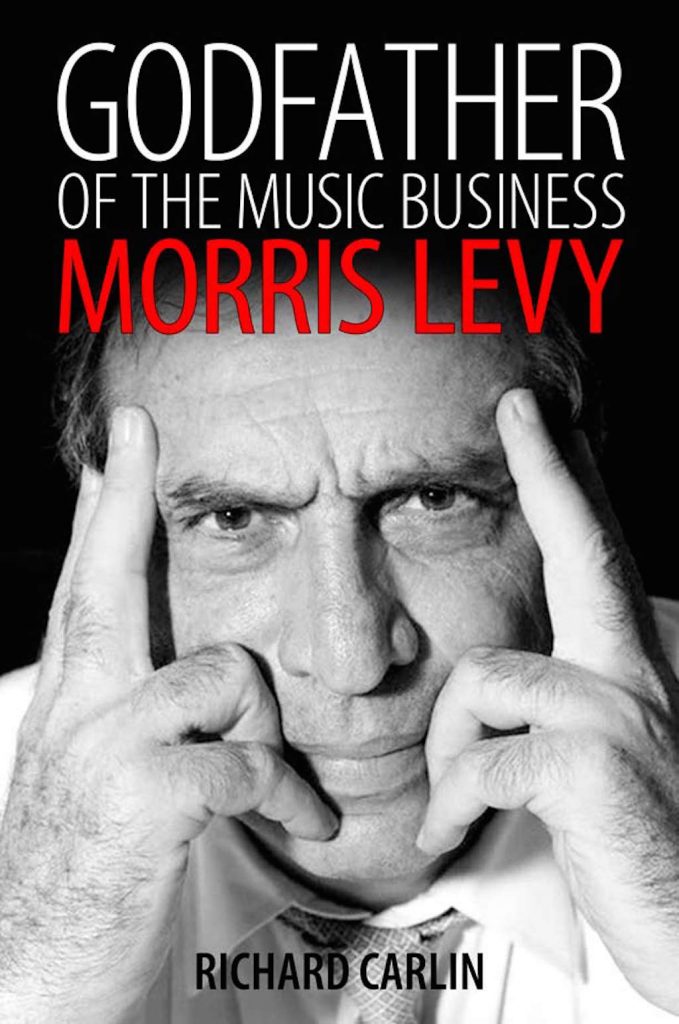

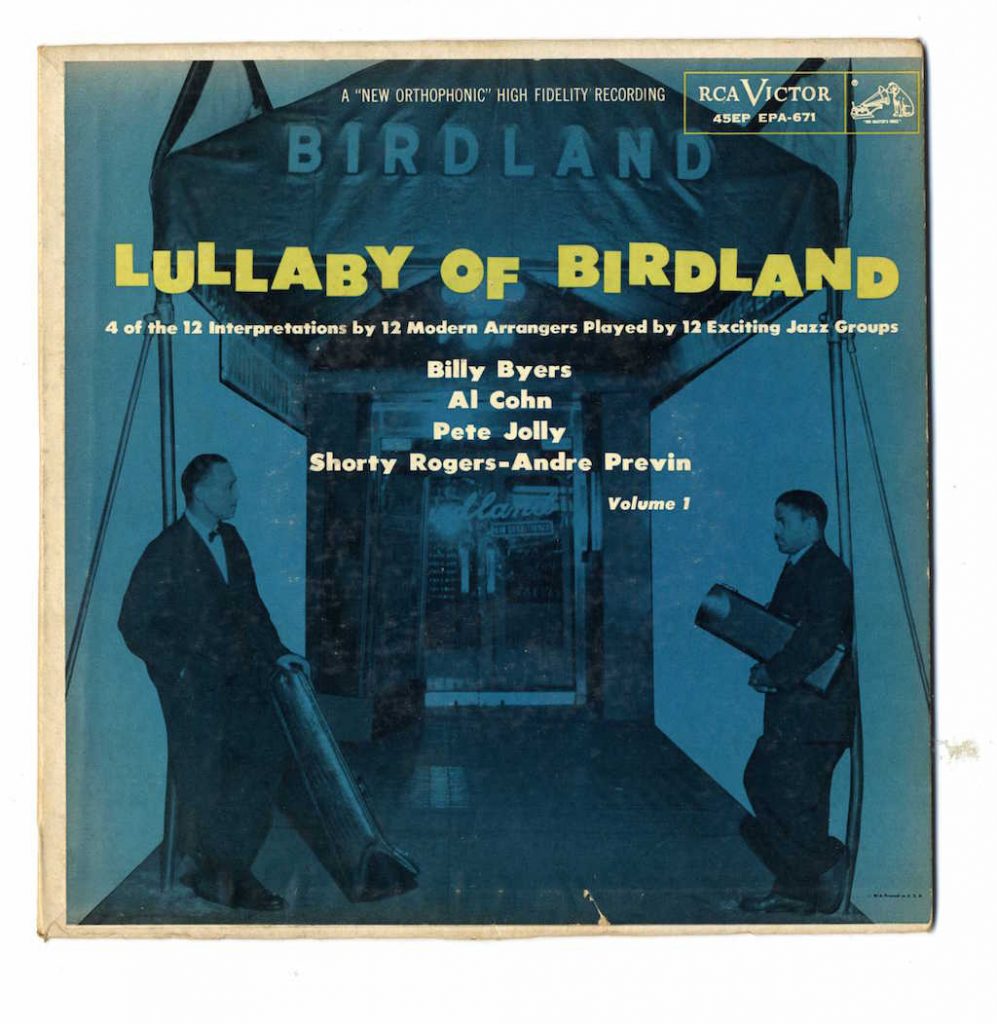

This book—an in-depth biography of Morris Levy, a legendary music business figure with reputed “mob ties” —is long overdue. We seem to have a collective fascination for scoundrels, thugs and gangsters. But Levy was no mere thug: from his Birdland, a midtown jazz club where Charlie Parker, Coltrane, Monk, Miles, Bud Powell and Count Basie played, to his mass marketing of pop music in the decades that followed, Levy had a keen sense of where the business was headed and capitalized on it. Yet Levy always remained a shadowy figure, even decades after his death. Nobody seemed to want to touch his story.[1] I’m very glad Richard Carlin finally did.

Carlin’s telling is filled with the sort of period detail that reveals an understanding not only of the industry’s history, but its complexity. The post WWII era–of hipster jazz clubs and singles-driven shoestring independent labels and publishers along with a few sleepy corporate giants still catering to a square, adult market – was literally exploded by a new, and as yet untapped, youth market. Levy exploited this with foresight, ruthlessness and commercial savvy.

Levy’s evolution from a poor, uneducated hat check clerk to record business mogul would be humdrum if it were only the usual tenement to boardroom story. But Carlin’s book traces the arc of Levy’s transformation (and that of the industry) by describing how Levy managed, manipulated, and levered his way to power and that story is fascinating. Levy saw innovative ways to capitalize on radio play as a promotional tool beyond conventional “payola”; created live “rock and roll events” that were aimed at the new, younger market, and quickly learned that owning song copyrights was a powerful mechanism to get rich by a continual, long-term stream of pennies, nickels and dimes. Levy didn’t just go from impresario to publisher to record label, but combined them to work together, synergistically; through interrelated companies and enterprises, he leveraged his acts by promoting them through clever venue arrangements, and then scored again, through record sales and publishing when the songs and acts caught fire.

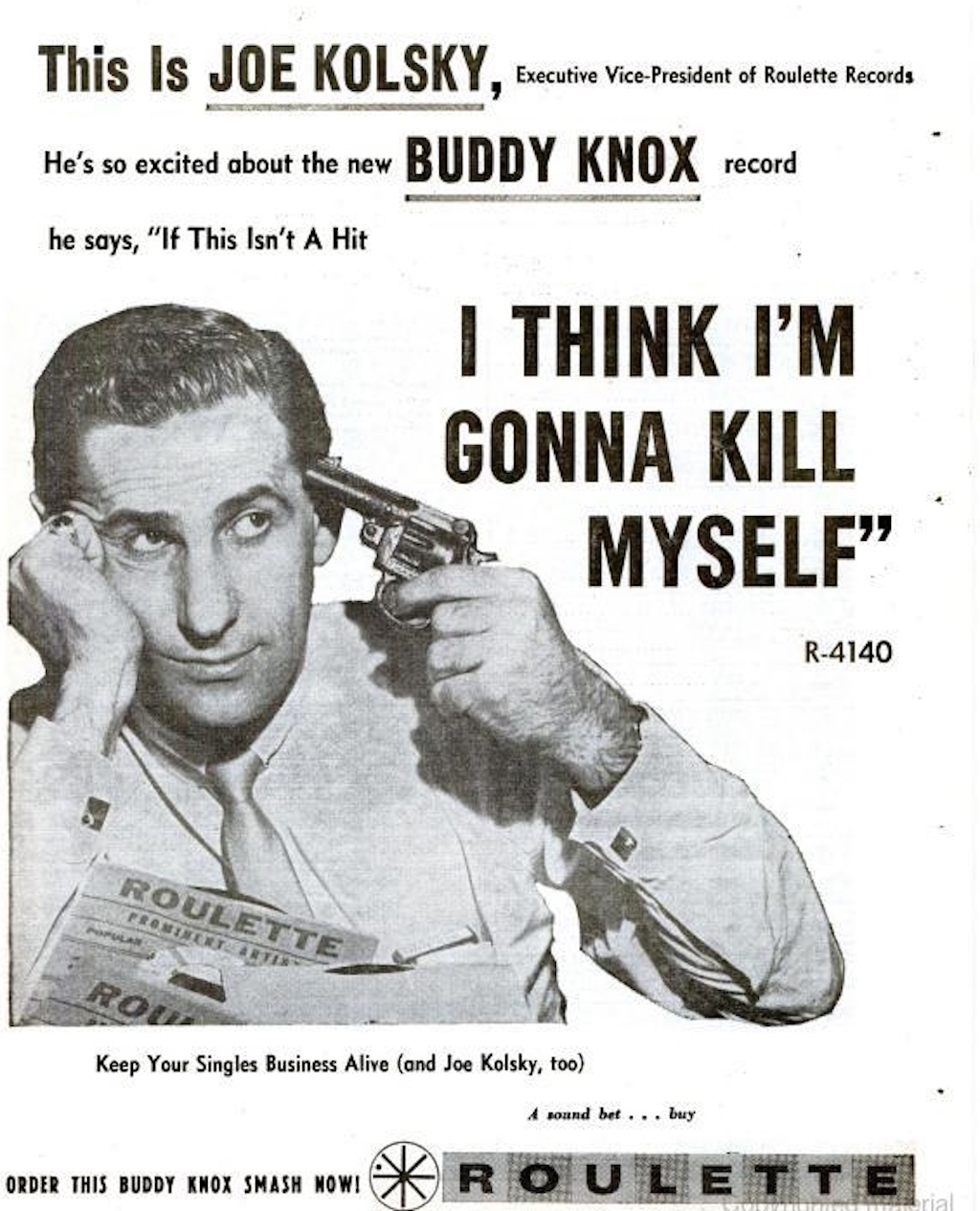

Levy spread tentacles through all aspects of the business, each serving the other. This eventually led Levy to Alan Freed, who later became the poster boy for the payola scandals to come. This was also the beginning of Roulette Records, an integral part of Levy’s growing empire.

The payola scandals eventually came to a head, fanned by lurid media accounts of the industry’s excesses. Levy was unscathed but Freed became the scapegoat, and ultimately, an industry pariah forever associated with the practice.

Levy was known as a tough guy within the industry and became a celebrity outside of it. Famous for his line, “you want royalties, go to England,” Levy was hardly the only publisher or record label that failed to account to a songwriter or recording artist.

One of the reasons I was drawn to Carlin’s book was the “mob” connection- it has always been veiled by innuendo, but even after Levy’s death in 1990, there was little specific detail.

Carlin describes the various relationships Levy enjoyed with known or reputed mobsters. At first, it seems like business as usual, except for the occasional beating in Levy’s offices.

The FBI eventually became interested in Levy’s business and associates. Levy had at least thirty different publishing, management and recording operations, which attracted the attention of the IRS as well. All of this generated industry gossip and tabloid interest, at a time when Levy was struggling to expand Roulette and become a major player in the record industry.

Levy was smart enough to tap into his back catalog years before the “oldies” market became an entrenched niche. He also had no shame in riding the wave of trends—from comedy albums, to schlocky parodies of big hits by others. But none of these was enough to lift Roulette into the top tier of labels—instead, Levy’s business became increasingly complex; selling remainders (left over stock from other labels) that could be resold at significant discounts; foreign imports (which made up a fraction of record sales in the United States) and compilation albums (usually “oldies” from the Roulette catalog and other labels) which were telemarketed like K-Tel. (Levy also licensed tracks to K-Tel). Levy bought up a bankrupt chain of record stores — Strawberries Records, allegedly with Mob funding. The revival of doowop (think: Happy Days and Sha Na Na) pumped in more revenue from the older catalogs but there was no single jackpot and Levy’s “old school” practices of screwing writers and artists was catching up with him.

By the ‘80s, Roulette was barely functioning as a real label, and Levy’s byzantine business structure was increasingly complicated by more direct Mob involvement. Carlin’s book becomes peppered with more and more names of reputed or later established Mob figures, some of whom you’ll recognize.

The deal that brought him down was, as often the case, a mundane, though sizeable transaction for remainders—seventy tractor trailer loads which, the buyer soon learned, had already been “cherry picked.” The buyer pushed back, Levy, who had some role as guarantor of payment and intermediary, started demanding payment and Levy’s business associates started to get short-tempered. Much of the back-and forth was caught on wiretaps, and eventually led to criminal charges against Levy and some of his cohorts, who were already being investigated for a host of other charges, unrelated to the remainders deal.

Levy vigorously defended against the charges (conspiracy to extort), claiming he himself was extorted and acting under duress; his counsel used the FBI’s evidence that Levy was controlled by the Mob to show precisely that. Carlin recounts the legal machinations with the precision of a lawyer, but none of the boilerplate. Levy was convicted, but remained out of jail on bail while awaiting an appeal (which he lost) and sentencing (Levy got ten years and a fine of $200,000). Levy had already been selling off assets, including the Strawberries chain, which was purchased by a company headed by Jose Menendez. The same Menendez who, along with his wife, was later murdered by his sons in a case that many first believed was a mob hit.

Some in the industry defended Levy- a rough guy, in a ruthless industry, but a man of his word. Levy himself once said, “I may fuck you on a contract, but I always keep my word.

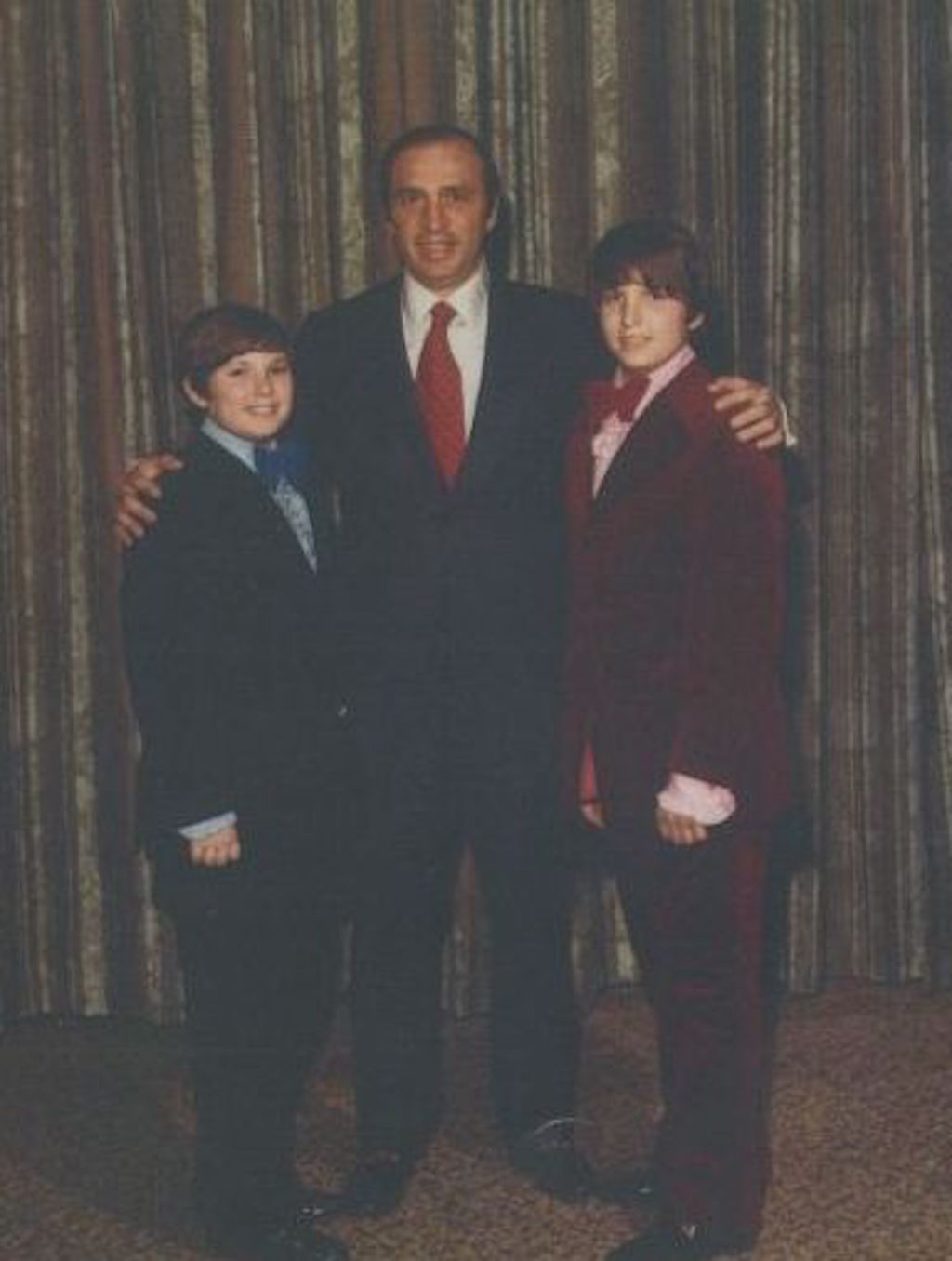

Morris Levy, circa 1973, with Howard Fisher’s sons, image courtesy of the Fischer Family via the author.

Levy died of cancer before he could spend a night in prison.

¤

Carlin comes out about where I do, after reading his tightly written prose. The nightclub business was rife with corruption and as Levy progressed in the music business, he took advantage of his contacts, to the point where he had no way out. He clearly relished his tough guy image and used it to his benefit during his rise and peak. Although in no way an apologia for the artists he screwed, Morris Levy became a victim of his own ruthless code of conduct.

Having lived in New York and worked in the city for many years, I have a hard time imagining New York, particularly 40 or 50 years ago, without the influence of unsavory elements. A business involving the manufacture, distribution and sale of physical goods (records), with up-front production costs, long lead times for payment and multiple intermediaries—from studios and pressing plants to distributors, jobbers and marketers— means everybody gets a piece. That’s how most legitimate businesses work in a fully lawful way. When it goes unlawful, a skim, a “backdoor sale” or a systematic failure to account and pay, the law eventually catches up.

I lived in the city during the waning days of the Mob—heavy prosecution of the hardcore gangsters, age, mob-wars and eventual changes in business took their toll. But everybody, at least everybody living in the city at the time, knew there was a certain “give a little to get along,” whether it was greasing the guy at the door, paying a little extra to the valet to keep your car out front or not making an issue with somebody who clearly “vibed” dangerous.

I’m sure there were a lot of wanna-be’s and guys who played up their “connections” too. I may have met a few along the way, and you might have too.

I don’t mean to be blithe about the Mob, but we live in a day and age where the criminal element now wears the mantle of political office or other legitimacy and manipulates numbers, people, the media and our food, fuel and war on a worldwide scale. The old- time Mafia is almost a quaint piece of nostalgia, like the old West.[2]

As for the review part: buy the book. It’s a fascinating account of the NY club scene in the aftermath of WWII as the music business morphed into the “record business” and all that entailed: it is as much social history as it is biography and the Mob elements seem to be a natural part of the story. It reads like a noir novel, tight and spare. From my vantage point, having worked as a lawyer in Manhattan in a considerable number of music-business related matters over the course of 34 years as outside counsel, Carlin gets the details right, at least on how the business is supposed to work. The book gives you a strong sense of who Morris Levy was— somebody who was a little scary (ok, a lot scary), who could be charming, who was probably always thinking of the next angle and was in some ways, a brilliant hustler. He also made some very tough friends, but none of this is sensationalized. Carlin reports everything in an almost matter of fact way, letting the actual events fill in the drama, the irony or the dark, closed-in atmosphere. The book also manages to convey a little of that New York “wiseguy” attitude that almost every New Yorker (whether or not a native) will immediately recognize and occasionally adopt. Although I never saw anybody get beat up in an office, and nobody ever pulled a gun on me in a meeting, every once in a while I had a sense there were some “guys” that I didn’t really want to know. And I didn’t know them.

Godfather of the Music Business: Morris Levy

by Richard Carlin

University Press of Mississippi 2016

Richard Carlin is the author of several books on popular music, including Worlds of Sound: The Story of Smithsonian Folkways and Country: The People, Places, and Events that Shaped the Country Style. He was the coeditor of the book “Ain’t Nothing But the Real Thing”: How the Apollo Theater Shaped Black Entertainment, and the editor of the 8-volume series America’s Popular Music. He has been an editor of music books at Schirmer, Routledge, Pearson/Prentice Hall, and currently Oxford University Press where he is Executive Editor for College Music and Art textbooks. His book, Godfather of the Music Business: The Life and Times of Morris Levy, was published by the University Press of Mississippi in 2016.

I talked to Richard Carlin about his work on the Morris Levy biography shortly after it was published. Here’s the Carlin interview.

____________________________________________

[1] Frederic Dannen’s Hitmen, which I read years ago, acknowledges Levy role in the industry and his “connections,” but Levy is not the focus of Hitmen, which aims more broadly at a host of colorful, sometimes vulgar characters. Tommy James’ more recent Me, The Mob and Music, centers on James’ trip to NYC to meet with various labels after getting a regional hit with “Hanky Panky.” He later learns that he has been signed to Levy’s Roulette label, and was told, essentially, “don’t ask.” Carlin presents several different accounts of the Tommy James “signing” story in this book.

[2] As mentioned at the outset, the public fascination with the Mob and gangsters generally could fill libraries. One solid overview of the New York families is Five Families: The Rise, Decline and Resurgence of America’s Most Powerful Mafia Empires by Selwyn Raab.

All photos (except the Dinah Washington/Roulette label image) are courtesy of Richard Carlin and any further reproduction is expressly prohibited.