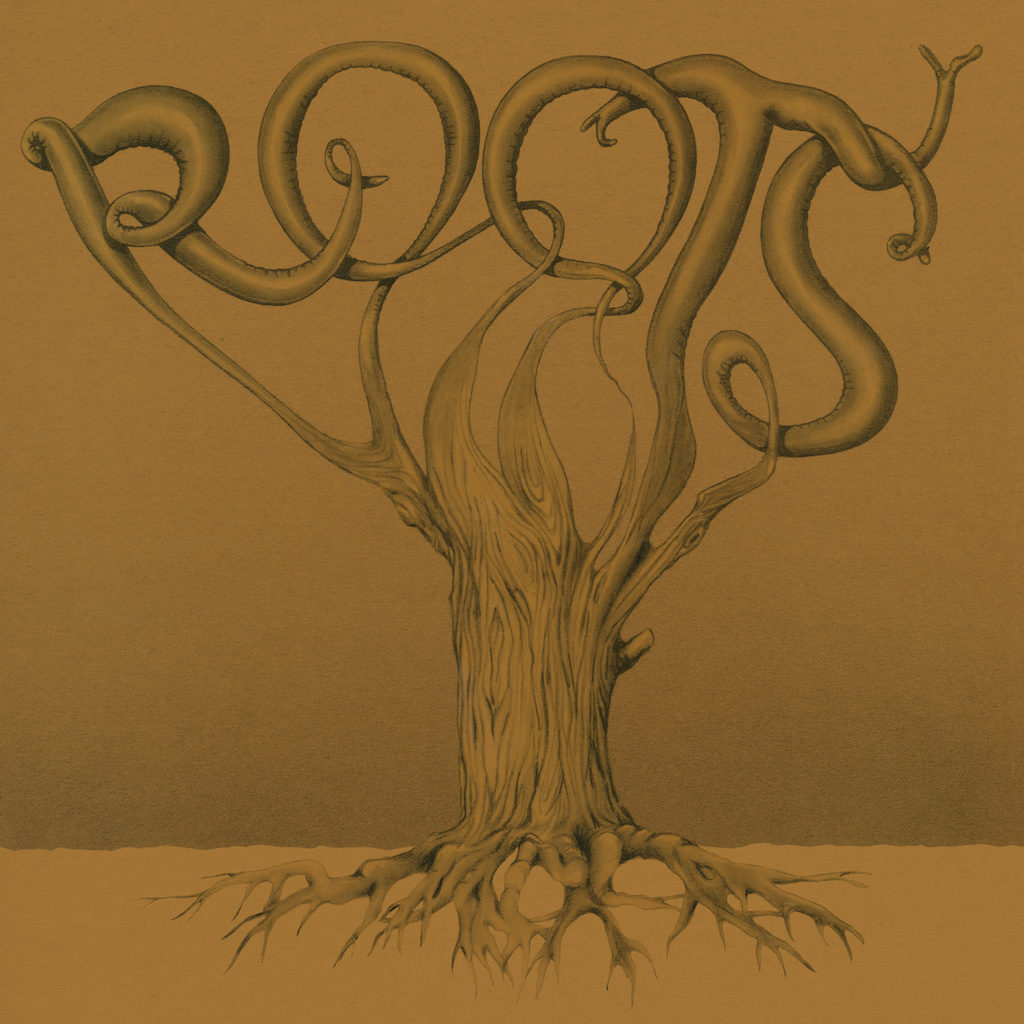

Roots- (Barney Rachabane)

Roots self-titled album, featuring Barney Rachabane, is somewhat obscure here in the States despite the international recognition accorded Mr. Rachabane for his work with Paul Simon and his legendary status in South Africa as a horn player of the first order. Roots was a group formed by Rachabane and treated as a one and done, although the group did issue one other album under the Roots moniker.

Rachabane is probably best known for his touring in support of the Graceland album for two decades. Yet his musical roots extend far deeper, as one of the living legends of the South African jazz scene. This album, first released on the Highway Soul label in South Africa in 1975, commands serious money for an original copy. It has not been reissued until now and we have Frederiksberg Records to thank for making it available.

Frederiksberg is a labor of love for Andreas Vingaard, who has tasked himself and his team with reissuing hard to find, rare records. [1] We’ve spoken several times, both about this record and some others in his fledgling label. This is not a business in which one gets rich. In fact, Andreas does it despite the cost and risk:

I’ve always loved music and telling stories. By running a label, I get to combine two passions. It’s certainly hard work and there’s pretty much exactly zero money in doing reissues of obscure jazz records if you consider the time that goes into it. I really enjoy doing the research and interviewing people. Obviously running a label is much more than tracking down people and looking in old newspapers. However, I feel it’s important work and it gives me great pleasure.

Barney Rachabane is hardly an obscure figure in South Africa—apart from his association with Paul Simon, he is a beloved figure who has a fair number of albums to his credit along with numerous appearances as an instrumentalist and performer. His style is not cutting edge or avant-garde. To the contrary, there is something very comforting about his sound, which conjures up the best of the old school straight ahead jazz sax styles; he has a stylistic flair that undoubtedly owes its origin to his life in Africa, but it’s an authentic part of his long experience as a musician. That is, the African influences here are subtle, and not overt.[2]

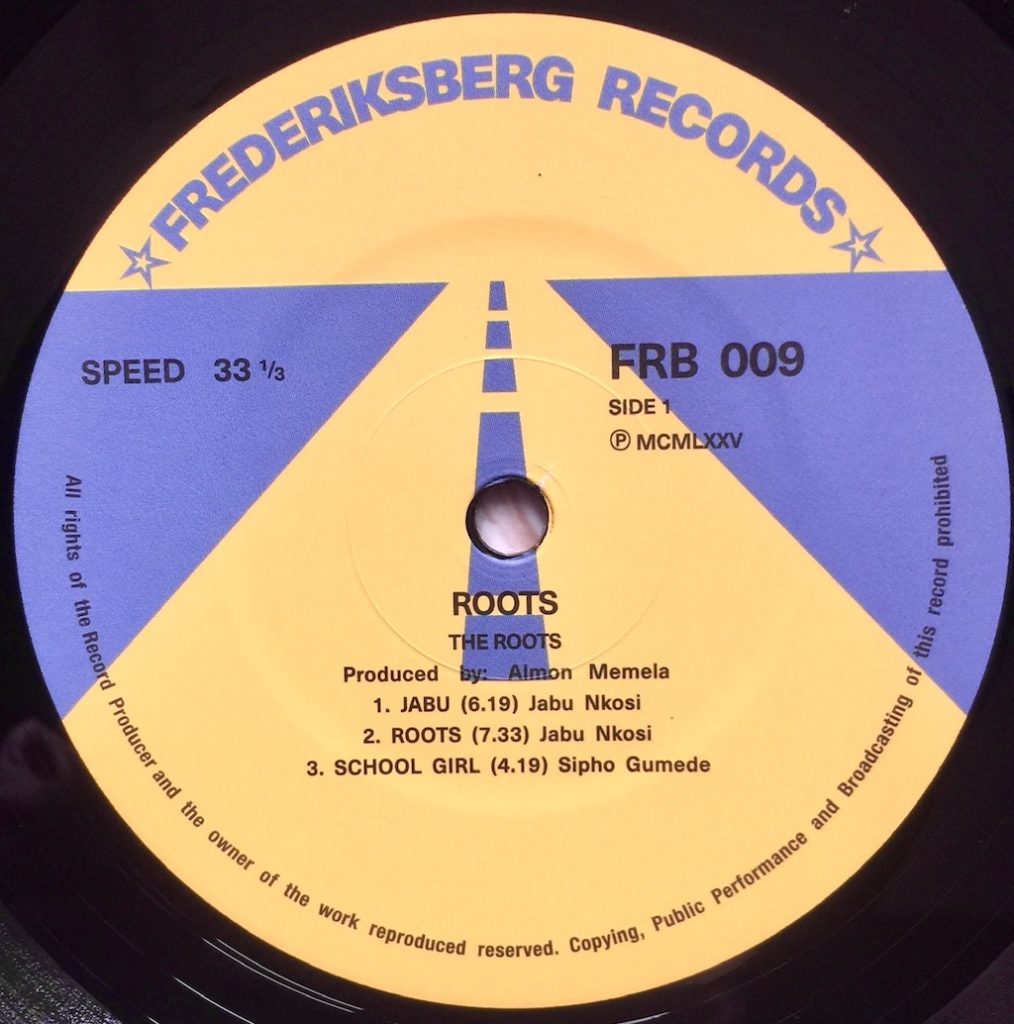

This album was made at an inflection point in Rachabane’s career when he began releasing albums as a featured performer; he had reached a stage of maturity that is reflected in his playing. The sound is full of soul, funky and its African influences aren’t contrived, but part of Rachabane’s life. The album is also commercial enough to be appreciated by those who aren’t steeped in jazz exotica and consists of three tracks on each side:

“Jabu”- a mellow horns in unison theme that offers an intricate solo after the first couple of refrains. The horn squawks occasionally, some triplets and counter-melodic runs intrude, but it’s mostly sweet, fast and returns to the main theme, with a switch to the other sax which is even more soulful. The piano picks it up next, then back to the main theme with all horns on board. It’s a big sound and everything sounds warm and harmonious.

“Roots” – another “all hands playing,” big sounding piece, with a joyously meditative sax solo. When you hear the other horns in background, they stage beautifully behind and seemingly above and to the left of the sax as the featured instrument, switching then to the deeper tenor sound, with cymbal taps and a chunky riff driven sound. There’s also a nice jazzy guitar interlude, rounded notes in that inimitable style of a Gibson or Gretsch hollow bodied electric with the treble turned down on one of the pick-ups[3] — some hi-hat work, and back to the full band, staccato riffs telegraphing the theme to the fade-out.

“School Girl”- starts with a funky strut, and the horns add warmth and size, reshaping the piece with an alto sax solo that is note perfect; hitting the minor keys against the main theme, with a cool run to the top of the scale, hi-hat opening and closing fast as hell, and the horns return full force, with what sounds like the same alto playing low-high against the full band until the track eventually fades.

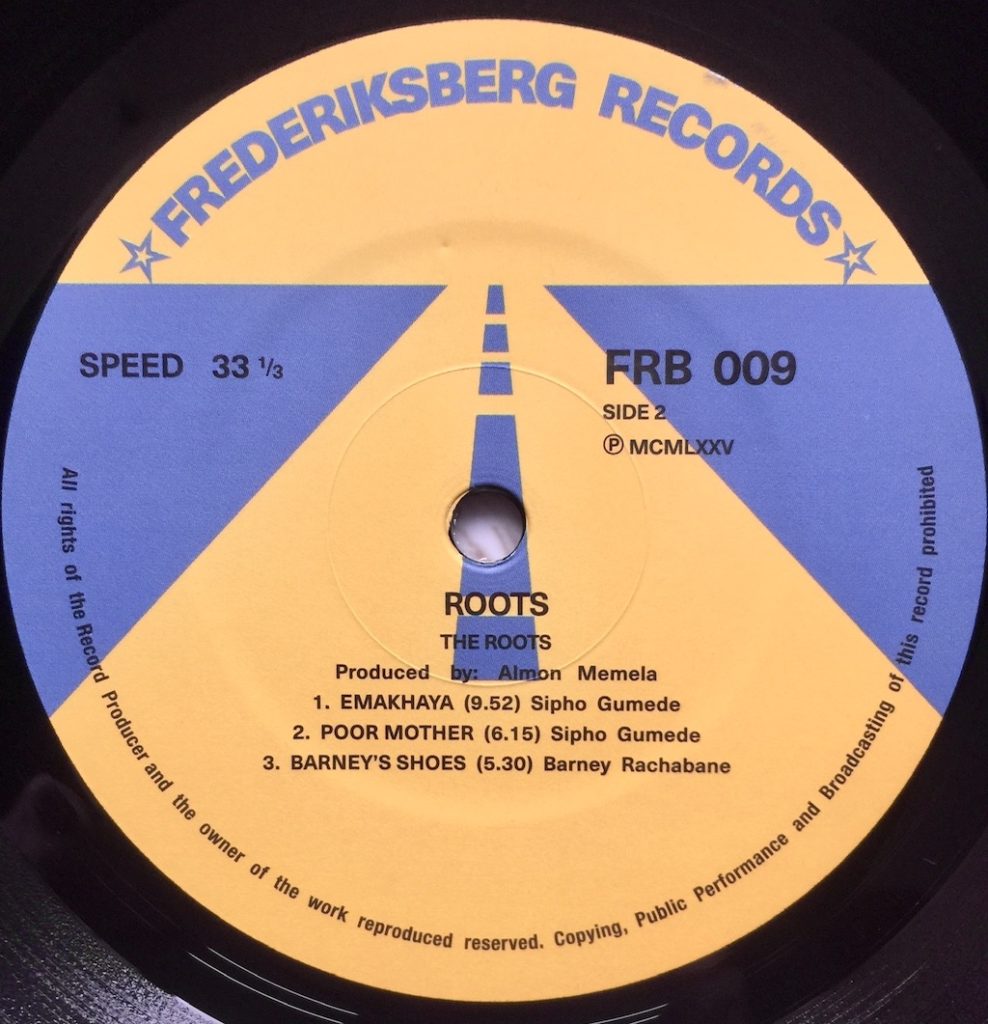

“Emakhaya”—repeated drumbeats set pace for flute rising and floating above the murmur of the band as the horn section comes in full on, in unison, paced to the offbeat. This composition is a little less traditional in style, the tenor sound is gorgeous here. The flute returns as a response, with lightness and delicacy, leading the band in an intricate weave, followed by a guitar interlude that combines jazz and blues. The full horn section returns in triumph to close out the track.

“Poor Mother”—a great old school sound that lays the groundwork for the tenor horn, backed by descending chords, with a theme that is readily identifiable. The alto horn takes a turn, and glorious it is, leading to a muted trumpet that is playing on the edge of distortion, the guitar picks up the motif with some intricate lead lines, and we return to a full- bodied sax and the band in command to the finish line.

“Barney’s Shoes”—more funk, played by a full band, with the hallmark of a more traditional sound that forms a backdrop for some wonderful solo work on the tenor sax hitting some great bluesy changes, what sounds like electric piano (or a distant piano in the mix) reprising the theme, then going into its own blues solo—playing a part that could have been written for horn. There’s a cool stutter in the rhythm track where the drums double time for a phrase to underscore the piano’s flight up register. The alto horn comes in to take us back into more familiar territory, but it’s a fresh take and the full horn section returns to bring the track to completion.

Although it has been characterized as a South African precursor to fusion, by today’s standards I don’t think this album is that far out. Instead, it takes a more traditional approach that mixes funk with jazz in way that would be comfortable to the mainstream listener. There are times when it has a very commercial sound rather than an avant-garde edginess, but what you hear is consummate players, at the top of their form, delivering a set of compositions that let them showcase their considerable instrumental prowess. In some ways, it is a time capsule—catching a moment between more traditional horn-led big band style sounds and the funkier, less predictable material that is so highly sought after today.

I can see why this album represents a milestone in South African jazz—rather than being trapped by its period, it is timeless. Though the instrumentation and arrangements, by today’s standards, are not discordant or inharmonious, it is still highly inventive and exploratory while staying rooted in a traditional jazz sound. It is, overall, extremely well played and well recorded.

There’s a big open sound to this reissue that belies its source. Andreas acknowledged the prejudice against so-called needle drops or working from an album as a source. In many cases, that’s all there is—the tape is gone. I shared the same prejudice once, as I think many audiophiles do—they disdain digital and anything that smacks of pulling something from an existing product—little wonder that Steve Wilson doesn’t even bother with the master tape and goes up a step to the multitracks, digitizes them and mixes from there.[4]

I’m all about getting access to more music and for records like this, where an original can easily get you into 4 figure territory for a clean copy if you can find it, this isn’t just a cheap substitute—it’s a fine sounding record that is accessible when the original is essentially unobtanium. No doubt if I got my hands on an original in great playing condition, I might take a different view, but at what cost to recalibrate one’s listening expectations and satisfaction? (I don’t even like handling records worth that much and I have had and still have my share of rare, valuable records).

The Frederiksberg reissue of Roots was pressed at Pallas in Germany and is a first-class slab of vinyl; that plant may be one of the top stops these days for consistency and quality. The jacket isn’t quite as heavy weight as some of the tip-on jackets now being used again for audiophile records, but I’ll always trade-off those more expensive extras for a better-quality LP. (How many of these deluxe reissues come with fancy packaging and crappy vinyl—quite a few in my estimation. At least Frederiksberg has their priorities straight). Some copies may still be available directly from Frederiksberg at their Bandcamp page below, but otherwise, you’ll be going to the secondary market and paying a few dollars more. It’s well worth it for a classic like this, particularly if you are more inclined to traditional styles, rather than the more outré styles that are currently in vogue.

https://frederiksbergrecords.bandcamp.com

Bill Hart

Austin, TX

March, 2021

__________________________________________________________

[1] I first encountered Mr. Vingaard because I heard that he obtained the rights to legitimately reissue Milt Ward and Virgo Spectrum. The Milt Ward album was a known quantity in collector’s circles but very little was known about Ward or the back story of the album, covered here in some depth. More on Milt Ward later, when we cover the forthcoming Frederiksberg reissue of that album.

[2] I’m no expert on South African jazz, so I invite comment from those with any depth of knowledge. Just as a point of contrast, while I was working on this review, I happened to be playing a live Horace Tapscott album to warm up the system. Tapscott was the leader of a West Coast ensemble that wasn’t quite as far out as Sun Ra but was pretty out there and depended heavily on chanting, massed voices, and rhythmic drum accents as well as some stunning avant-garde playing. Filtering the African experience through an American lens isn’t the same as what I hear on this record –which has none of these elements. Though it might suggest I’m criticizing Tapscott for heavy-handedness, there is something absolutely gorgeous about Tapscott’s records-perhaps it’s in the contrasts of sheer beauty amidst the cacophony and dissonance.

[3] Truth be told, I have no idea what instrument the guitarist is playing- as far as I can tell, he or she isn’t even credited. But you know the sound I’m talking about, it’s a classic sort of Wes Montgomery, Chet Atkins style of tone.

[4] I had my own epiphany several years ago hearing the work in progress restoration of the Benny Goodman 1938 Carnegie Hall concert- taken from a series of transcription discs cut for Goodman’s personal use and never intended for commercial release. The archivist who restored the recording brought it to life in a way that no one has been able to hear since that concert was performed.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.