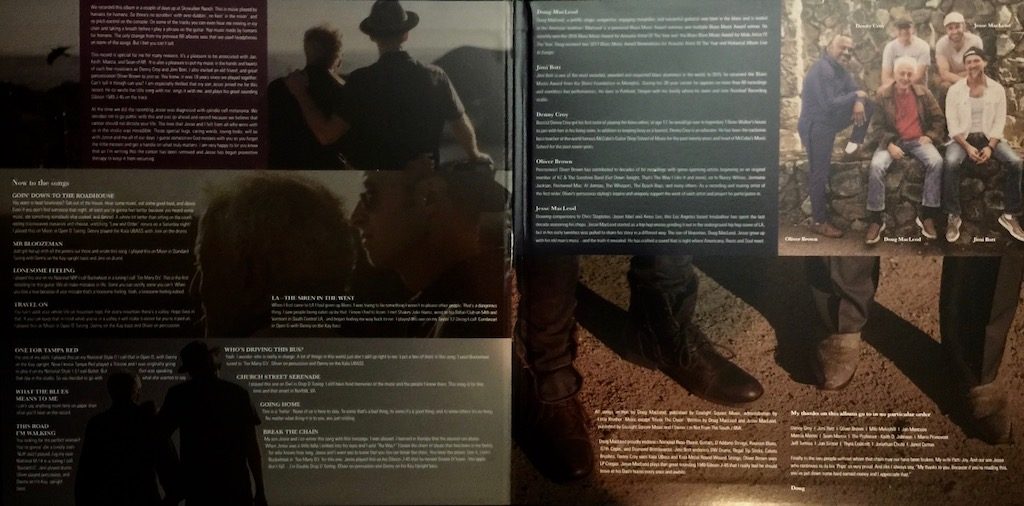

The Talking Blues-Doug MacLeod’s Break the Chain

I’ve always liked the blues. In some ways the simplest, yet often the most difficult music to play: the changes are easy, and while many players stun with instrumental virtuosity, what really sticks (for me) is the raw, emotional outpouring, not the flashiness. Sometimes it just falls flat because it seems like you’ve heard it a million times, and it is being played by rote.

Doug MacLeod’s Break the Chain, recently released on the audiophile label, Reference Recordings (more about the label and production below), is in some ways a throw-back to the age of country blues—not quite rural but certainly not the Chicago blues of Chess, Delmark and other ‘50s-‘60s era of electric blues or the later, British-born blues rock that was inspired by all of it.

MacLeod is a storyteller and a master of nuance. The record (actually two LPs, cut at 45 rpm), is part spoken word, part poetry against acoustic guitar and a band that never makes itself front and center. There are a lot of soft, quiet passages to this recording, and in the hands of anyone other than a maestro recording engineer, I’m not sure that would be conveyed effectively via a recorded performance. (One reason why many artists are better “live” than on record).

MacLeod has been around the block a few times. Although born in New York, MacLeod was raised in North Carolina, has lived in many other places and has been making music for more than fifty years. He is often quoted as saying “Never play a note you don’t believe“ a truism observed more often in its breach. MacLeod learned this, and more, from Ernest Banks, an old time bluesman he met in Norfolk,[1]where MacLeod was stationed in the mid-‘60s, playing the coffee house scene.

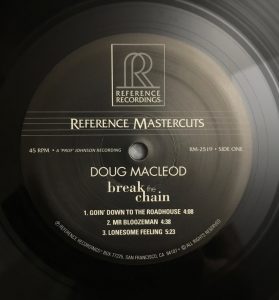

The Album

side 1

“Goin’ Down To the Roadhouse”- a county boogie, sung with lilt, the metallic sound of resonator slide guitar brings you back in time and place; the bass line is muted and melodic, rather than being close mic’d and in your face in a hyper-real way that is plainly artificial. (It may sound good on a hi-fi to have that “zoomed in” micro-detail of the instrument creaking, but you don’t usually hear that at a live performance and the instrument’s proportion is “off” in relation to others when recorded that way).

“Mr. Bloozeman”- drums set the pace, a slow crawl, dissing “The Bluesman”—the cartoon caricature of one anyway.[2] There’s a line in the song: “Dynamics, taste, space and groove are tools you’ll never use.“ That captures part of what makes his music special; in MacLeod’s words, “it’s honest.” There’s a nice single lead line combined with double stops on guitar and a dissonant finish that is perfectly appropriate, like a sour taste.

MacLeod told me: “I met Ernest [Banks] when he was playing the juke joints in Toano, Virginia (between Norfolk and Richmond); as soon as I heard him, I knew I wasn’t the real deal.”

That marked the beginning of a learning process for MacLeod, who says that Banks taught him about the “honesty” of the music; Banks didn’t actually “teach” MacLeod anything; instead the younger MacLeod learned by listening and absorbing—the music, the anecdotes, the perspective of the thing. That was also when MacLeod first straddled what he calls “cross-culturalization”—trying to understand the blues from the perspective of its originators.

“Lonesome Feeling”- presents a very old school slide sound a la Blind Willie Johnson— lots of little details in the playing with just the right kind of texture, harmonics, and resonance of the guitar. The artist isn’t just trying to conjure up ghosts from the past– the lyrics speak to us today: “it’s a lonesome feeling when you can’t make right what you did wrong.” Doug’s voice is raspy and somewhat wistful here.

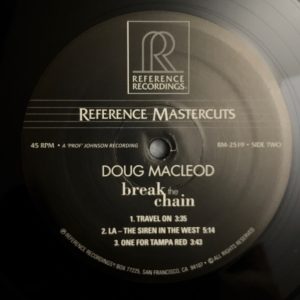

side 2

“Travel On”- Lots of shimmer and slide on that guitar. According to MacLeod, Ernest Banks taught him to use the bottleneck as a voice. That, in turn, led to MacLeod’s discovery of Tampa Red, to whom a song is devoted on this album.

“LA- The Siren in the West” -a loping shuffle with classic boogie line–Doug’s voice is great on this track—“Walking on this avenue filled with stars….”

“One for Tampa Red” – a nod to a legendary, forgotten bluesman known for his beautiful single note lead lines—slower paced, but not sepia toned—very alive sounding— and a fitting tribute.

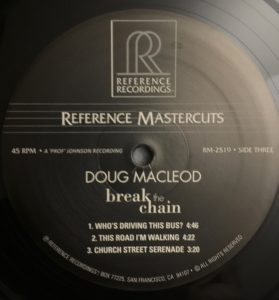

side 3

“Who’s Driving This Bus” is a deep boogie—love the rattle sound of the percussion; the song gets political but the question, “who’s driving this bus” is a perennial one.[3]

“This Road I’m Walking”—a quick paced, humorous track—at least with respect to women, I guess the blues really leaves you little choice but to “laugh to keep from cryin’.” I like how Doug and his band take the instrumental interlude into serious playing territory. You get the feeling of being at a live show. Great ‘snap’ of that resonator guitar at the end of the track.

“Church Street Serenade” – has one of those home-spun folk blues vibes– the kind of thing I hear whenever we go see David Lindley’s solo shows. It’s part folk, part Americana and definitely rooted in the past. Doug is a pretty serious guitar player in tone, dynamics, “taste and groove” and you get a chance to hear it on this track. Pretty stunning, arpeggiated chords, minor key changes. Beautiful playing and a sonic treat.

Side 4

“Break the Chain”— the title track has special significance. Co-written with his son Jesse (who also performs on the song and sings the last verse) but is part of the story: Doug’s struggle to get out of the cycle of abuse that had been handed down in his family—a legacy of pain to others and oneself in a vicious circle that carries on from generation to generation. The song starts with a cymbal shimmer that brings you inside the music—a great driving riff. Doug sings in the first and second verses (as the father): ‘You’ve got the power to make a change, [stop the pain], you’ve got the power to break the chain.” The song goes to a whisper, then comes back with a guitar lead and cymbal rolls- and a new melodic line, with Jesse (the son) voicing the refrain—“ain’t got no chain.”[4]

It’s a powerful piece on many levels—the very personal aspects shared by father and son and what amounts to a catharsis that is played out in the performance of the song itself. This is the stuff of real life, of hardship, disappointment and hurt. (And ultimately, redemption, perhaps, if the writer/performer has achieved it). It’s also why this album has a genuineness that takes us back to some of the early blues and reminds us why that music is so riveting. Hint: it’s not the sonics, or instrumental skill, though both are present on this album in abundance, but the ability to touch some part of us that is deep, hidden and rarely given voice.

MacLeod manages to capture the sound and feel of traditional blues without sounding derivative—that’s not just unique, it seems impossible. But, he has his own, particular take on the blues from his years of living and playing in many parts of the country[5]that— if not entirely different in spirit from what has been done in the distant past– is different in sound and approach. The music and sound is very distinctive and satisfying; after listening to all four sides, it’s like walking out of a club after a great set.

“Going Home”—sounds like a work song—unaccompanied voice- Doug shines here too.

“What the Blues Means To Me”- I played the album the first time starting with this side –MacLeod describes the feeling of playing the blues— through spoken word, but you can hear the music in his words— his philosophy is similar to Stanley Booth’s observation that the common thread in music is “redemption.”

Ω

Doug can count among his influences such seminal blues figures as “Honeyboy” Edwards and Robert Lockwood, Jr. Edwards was reputed to be the last person to see Robert Johnson alive, and Lockwood, Jr. learned to play from, and played with, Johnson.

I asked Doug how he came to meet “Honeyboy”:

I was playing a coffee house, doing my original material. In comes Edwards. I recognized him. I don’t know what got into me- whether I was brave or stupid, but I decided to play Johnson’s “Kindhearted Woman” that night. We connected and later played together.

Lockwood, Jr. put Doug to a different kind of test one night:

At one point, he [Lockwood, Jr.] saw me eyeing his twelve string- and asked me if I wanted to play it. I said yes, then he asked me if I believed all the legends about Robert Johnson. I said “no, I just think he was a really good guitarist.” Lockwood, Jr. said, “Go ahead and play it.”

I also asked Doug about Skywalker Sound and working with Keith O. Johnson:

I’ve been in some pretty big studios on the West Coast, but that place was enormous. Keith is very respectful, a nice man who truly loves the music. You’d think, being a genius, he’d be weird, but he’s not.

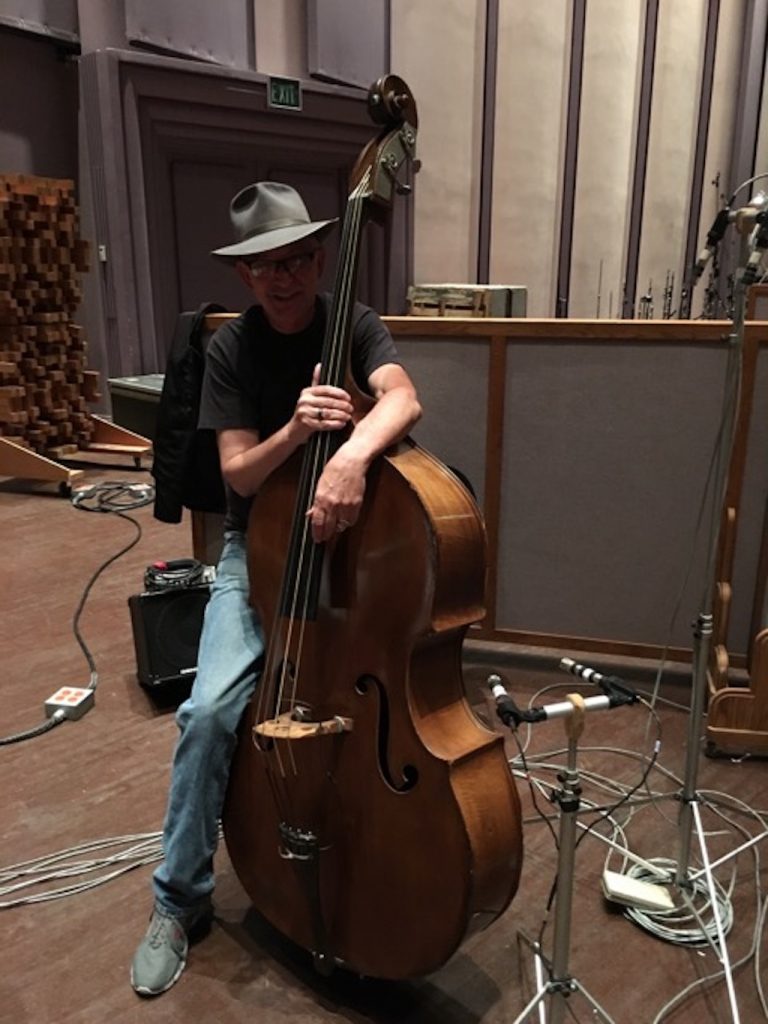

Keith O. Johnson recorded two albums with Doug MacLeod before this release (“There’s A Time” and “Exactly Like This”). This album was recorded and mixed by Johnson at Skywalker Sound and mastered to vinyl by Paul Stubblebine. It was pressed at Quality Record Pressings (“QRP”), a/k/a “Chad’s,” with a heavy jacket by Stoughton.

The album was recorded “live” in the studio, with no overdubbing, which contributes enormously to the “you are there” quality of the sound. The recording is digital, recorded at 176.4kHz/24 bit, and it benefits from absolute black backgrounds that medium offers while, at least in Johnson’s hands, has none of the flat, dead, bright or lifeless sound that I used to associate with digital—digital has come in to its own and you can fully appreciate it on this record.

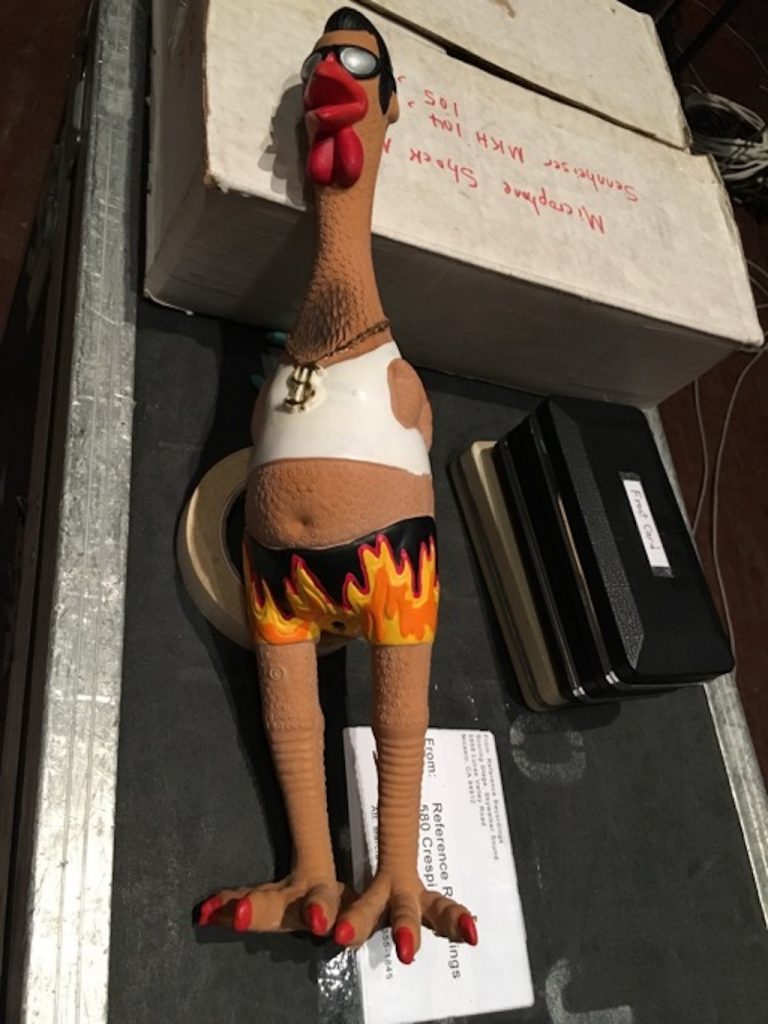

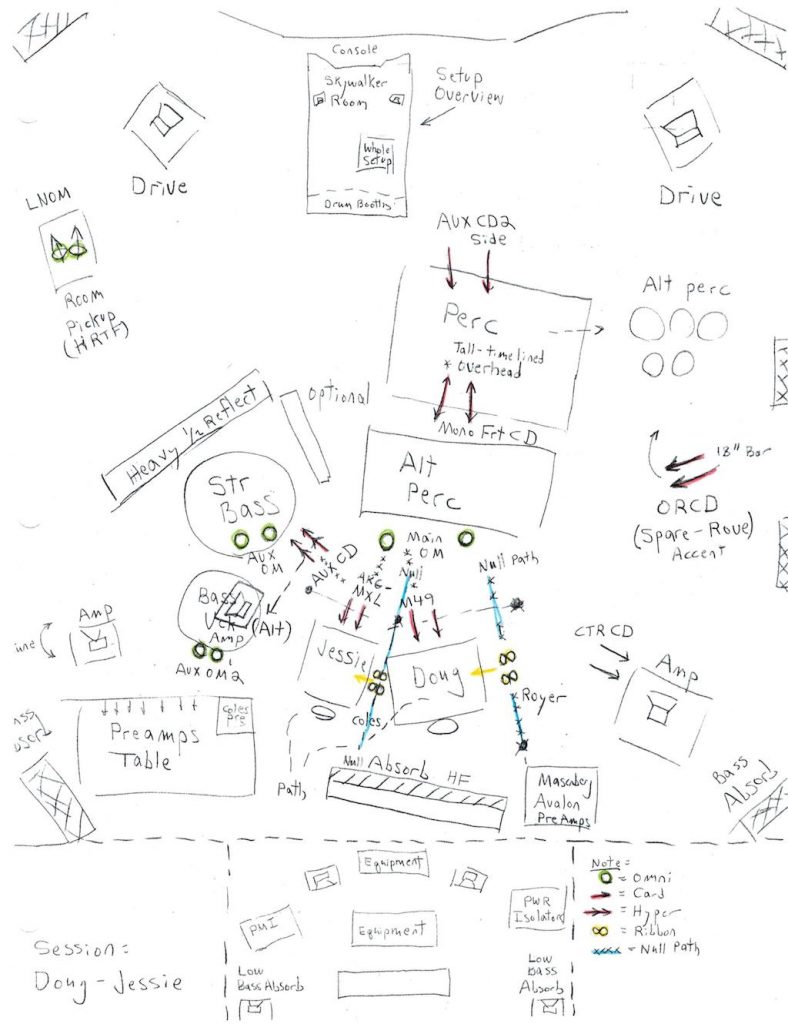

Johnson, a seminal figure in sound reproduction,[6]always uses his own custom built microphones and mic preamps. In this case, Johnson followed his usual practice, which is to say that the set up is different for every session (and each track). Johnson evaluates the room, the instrumentation, placement and overall sound to be achieved for each track, placing the mics just so. I learned that Johnson has a trick—the so-called “Elvis Chicken” that is one of many things he uses to evaluate the sound of the room, to help him better understand the acoustic space he is working in.

According to Janice Mancuso, who co-produced the album and is a long time fan of Doug’s, Johnson used many mics in these sessions but does not record in multi-track fashion. Instead, different mics in different positions are active for certain tracks, but not others. The essence of this recording technique is ‘live in the studio’ aimed at capturing what transpires, with nothing added or changed. There is no “fixed in the mix.”

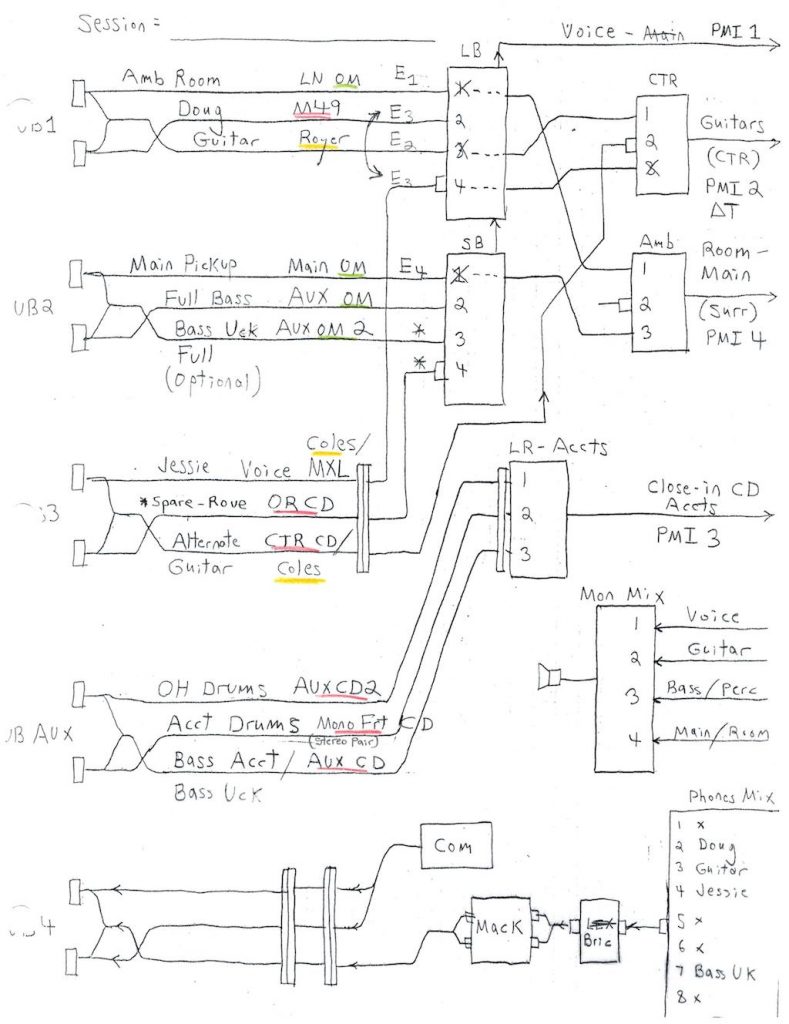

Here are some diagrams that were provided to me for the set up of the sessions:

The mic preamps and mixing boards are all proprietary, designed and built by Johnson.

Johnson uses his own microphones and added some Neumann vocal mics on hand at Skywalker.

The combination of “honest” music and spare, sympathetic recording techniques with no gimmickry yields an album that is both musically satisfying and sonically rewarding. If this is out of your comfort zone, try it. As a longtime fan of the blues, and of Keith O. Johnson’s work, it’s a classic.[7] I’ve now become a fan of Doug MacLeod’s as well. We hope to catch him as he passes through the Austin area in a few weeks.

Bill Hart

Austin, TX.

September, 2018

Photo credits: Feature images by Jared Cotton; other images courtesy of Janice Mancuso, all rights, including those of Reference Recordings and Keith O. Johnson, reserved.

My thanks to Doug and Janice for making this piece special.

_____________________________________________________________________________

[1]MacLeod said he suspected Banks had performed, and possibly recorded, under another name before he surfaced in Norfolk as “Ernest Banks.” Part of it was his style- he did not sound like he came from the area, according to Doug. We’ll leave that to a blues musicologist to unearth. The blues and its progenitors are shrouded in mystery and myth that seem to add to its allure.

[2]I asked MacLeod about that. He said he was talking “about the posers, the harmonica posers, the guitar posers” who adopt the trappings of a blues musician but wind up turning people off to the blues because they aren’t the real thing.

[3]This reminds me of Harry Dean Stanton’s observations about the fundamental misconception in life that someone is actually in charge. See Surrender to the Void. It is interesting to take this track in and absorb it in conjunction with some of the songs of Gil Scott Heron on Winter in America—different time, different perspective, but the same damn thing. See Winter in America.

[4]According to the liner notes, the song reflects the very personal experience of MacLeod in breaking the chain of abuse and violence in his family.

[5]Doug MacLeod has received his share of industry accolades over the years. This album garnered the 2018 Blues Music Award for Acoustic Album of the Year.

A prolific songwriter, MacLeod has penned such songs as “Nightbird,” the title track of a comprehensive release of Eva Cassidy’s work several years ago.

[6]Johnson won a scholarship funded by Ampex for a tape and mic project while still in grade school! He went on to develop a magnetic tape head technology utilizing photolithography technique for the head gaps while at Stanford, and worked on optical disc scanning (Disc-O-Vision) and polyphonic sampling (with Alan Parsons). Reference Recordings was founded by Tam Henderson in 1976, and Johnson joined him early on, recording RR-5. He has since recorded more than 150 albums for the label.

Johnson co-invented HDCD technology, was one of the founders of Pacific Microsonics and has long worked with Spectral Electronics.

His is a multidimensional world of engineering, music and technology at the highest levels. I have many of the original Reference Recordings LPs that I bought new back in the day. I also fondly remember the consortium among Spectral, Entech and Crosby Audio Works; the latter had developed a modified version of the Quad 63, which I owned and enjoyed for a number of years.

[7]As regular readers know, I rarely review “audiophile” records, though I own many—going back to the early records produced by Ewing Dunbar Nunn, through the Sheffield, M&K, Levinson, Wilson, early MoFi, Crystal Clear, and other odd and sundry labels. I asked for a copy of this record precisely because it would be musically appealing to me and suspected the sonics would be beyond reproach.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.