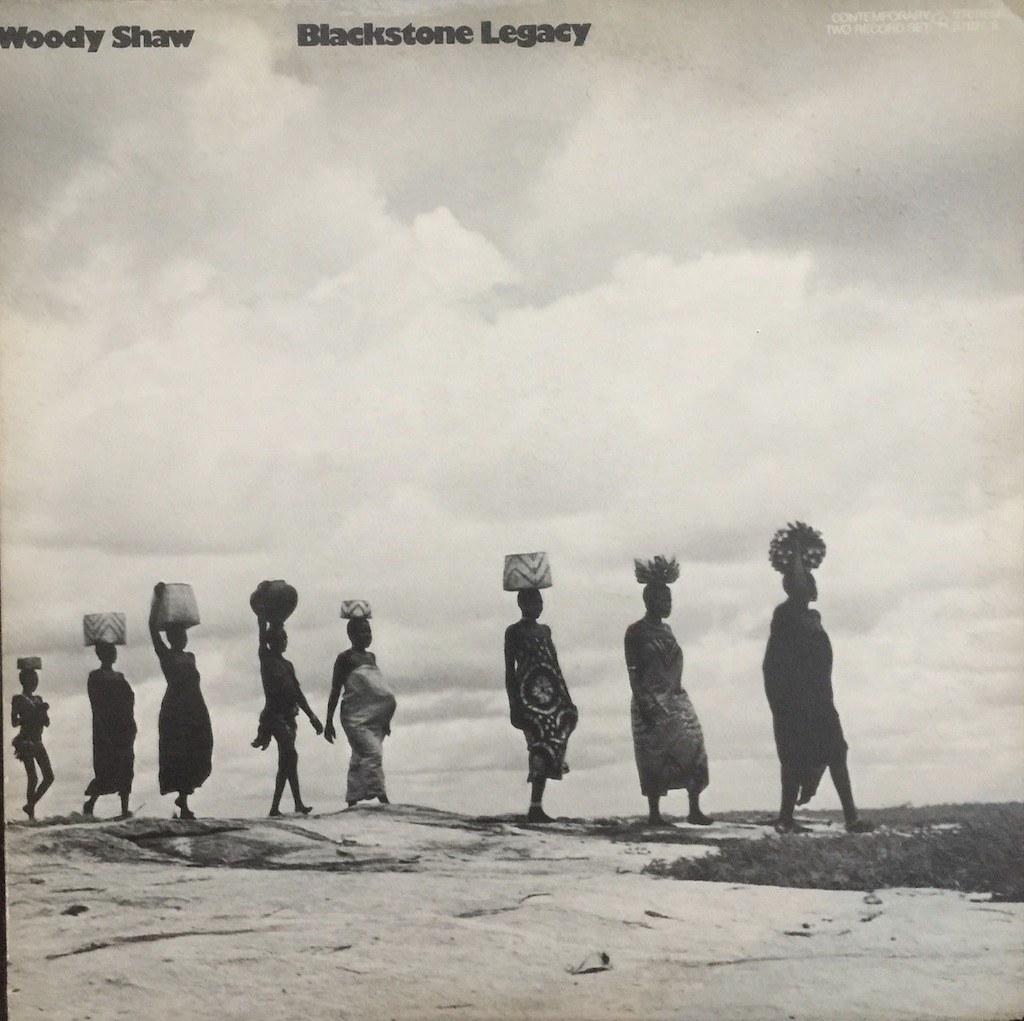

Woody Shaw- Blackstone Legacy

Woody Shaw’s Blackstone Legacy, his first as a featured artist released in 1971, may be one of his best. Shaw had a steady career as a sideman, working with some of the greats in Paris, including Nathan Davis (whose work after he returned to the States has been covered here), followed by a stint with Blue Note before embarking on a career as a bandleader.

After release of Blackstone Legacy, Shaw continued to work as a sideman at the same time he released a succession of albums as a featured artist. Shaw was prolific and died tragically at the age of 44, leaving a legacy of innovative performances that reflected his advanced technique. There was something very structured about his improvisation, and his influences were wide-ranging, combining African, European and mid-Eastern elements. Shaw had an impeccable playing style that demanded speed, articulation and great fluency; while technically adept, Shaw also managed to imbue his playing with soul and less conventional phrases and scales.

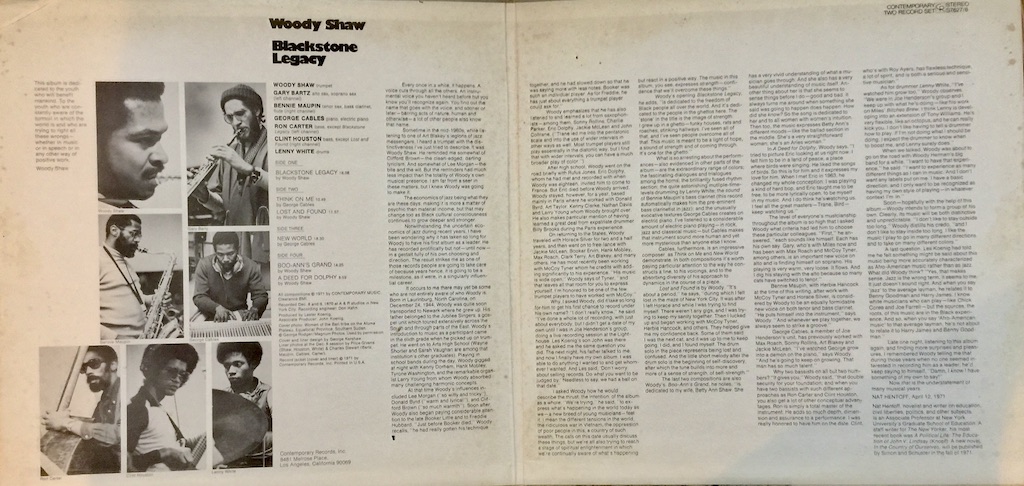

This album is not rare, but it is hard to find in unflawed condition. See, e.g., https://www.discogs.com/Woody-Shaw-Blackstone-Legacy/release/2478203 I had to be patient to land a good copy. The band is first rate and includes Gary Bartz, Ron Carter, Bennie Maupin and other notable players. The sound is a combination of avant-garde big band sounds combined with esoteric interludes. Most of the tracks are long, and the album takes up four sides.

The title track starts at full tilt, with all instruments aboard, the electric piano setting up an interlude for the horns to work around. The drummer, Lenny White, is working hard on this track. Gary Bartz’s playing is note perfect. The bass clarinet sounds are very distinctive; according to the liner notes (by Nate Hentoff), Maupin’s playing here “automatically makes him the pre-eminent bass clarinetist in jazz.” Hard to argue that one–the performance is stunning. There’s a hard driving quality to this composition that keeps it moving forward even in soft moments, when the bass is propelling the song, or when the horns aggressively attack and twist around each other. No navel gazing here- there’s an endless sense of movement. When the horns play in unison, it’s bliss.

Blackstone Legacy is followed by “Think on Me,” a beautiful, somewhat conventional sounding track that depends on various solos for its outré moments, but even those are harmonious—this is something that even someone unfamiliar with more avant-garde jazz could easily take in. The piano work here by George Cables is a real groove—bluesy, jazzy, classically framed. The ending, horns sync’d together, is wonderful.

Side two finishes with “Lost and Found,” starts with a drum solo that leads to a flourish of horn playing virtuosity and then returns to the drums, only to be interrupted again by the horns, plus bass and a cool solo by Maupin that is just a killer.

Yet for all the gifted players, any one of whom could command an album’s worth of performance, it’s arranged and produced in a fairly straightforward way—impressive playing (Lenny White’s drum work is wonderful), but accessible if you have an ear for less mainstream jazz.

Do not let me mislead you into believing that this is straight-ahead material- it isn’t. But it is well within the lines-George Cables sneaks in a cool electric piano solo into “Lost and Found” and it’s a classic sound.

“New World” has a cool bass riff and a wah-wah psychedelic quality combined with horns playing in unison, electric piano and an outstanding solo by Bartz.

Most of the tracks use two bass players—with a couple exceptions. (Clint Houston was the other bass player with Carter- the tracks where each stepped back are identified in the liner notes). There’s a lot going on in this record, but rather than sounding busy or cluttered, it’s like a rich feast—a sensory indulgence that never becomes excessive.

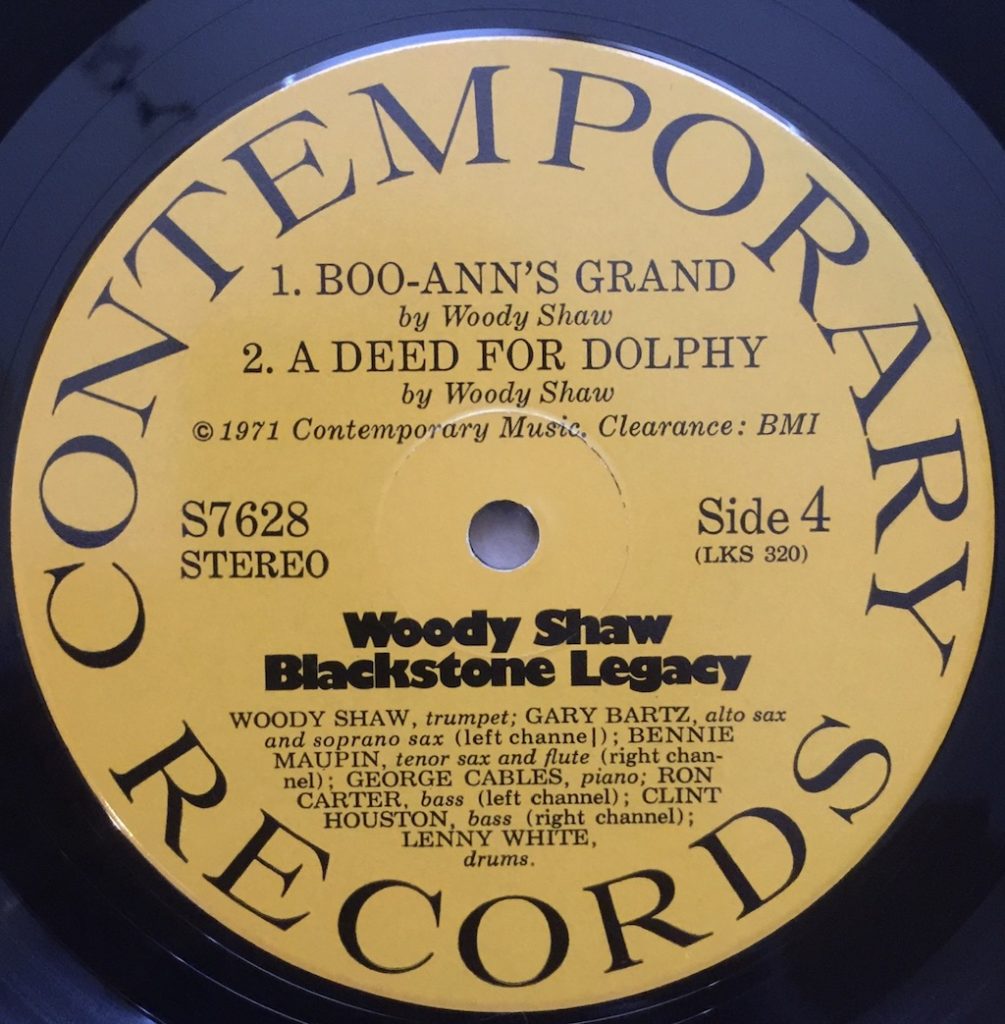

“Boo-Ann’s Grand” starts with a complete horn section at full throttle, but quickly slows and lets individual instruments develop a melody or movement within the composition—the piano playing here is sophisticated and intricate, with a classical motif—almost a study within a larger ensemble piece. It’s a very cool track. Bartz’s tonality is magnificent here. Nothing wild or edgy—just taking the lead and hitting notes that are grounded in the underlying composition, while expressing a sort of free flight unconstrained by any boundaries. This is the kind of structured improvisation I mentioned earlier.

The album ends with “A Deed for Dolphy” who has been the inspiration for so many great players. It’s a moody, darker piece, centered on the horns, with shadings of light and dark, backed by deft piano work, detailed cymbal play. The horn work, including the flute by Maupin, is glorious.

This is a killer record, perhaps a little under-rated, and it won’t cost a fortune, but you’ll have to be patient in seeking out a clean copy. Sonically, it’s superb.

Bill Hart

Austin, TX

Nov. 2020

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.